Lent is when Christians choose to give things up or to take things on to reflect upon the death of Jesus. For Lent, I took on this self-referential series about Lent, arguing Christianity is following Jesus, and that following role models are better than following rules because all sets of rules are ultimately incompete.

But how can we choose to follow Jesus? To many Christians, the answer is simple: “free will.” At one Passion play (where I played Jesus, thanks to my long hair), the author put it this way: “You are always choose, because no-one can take your will away. You know that, don’t you?”

Christians are highly attached to the idea of free will. However, I know a fair number of atheists and agnostics who seem attached to the idea of free will being a myth. I always find this bit of pseudoscence a bit surprising coming from scientifically minded folk, so it’s worth asking the question.

Do we have free will, or not?

Well, it depends on what kind of free will we’re talking about. Philosopher Daniel Dennett argues at book length that there are many definitions of “free will”, only some varieties of which are worth having. I’m not going to use Dennett’s breakdown of free will; I’ll use mine, based on discussions with people who care.

The first kind of “free will” is undetermined will: the idea that “I”, as consciousness or spirit, can make things happen, outside the control of physical law. Well, fine, if you want to believe that: the science of quantum mechanics allows that, since all observable events have unresolvable randomness.

But the science of quantum mechanics also suggests we could never prove that idea scientifically. To see why, look at entanglement: particles that are observed here are connected to particles over there. Say, if momentum is conserved, and two particles fly apart, if one goes left, the other must go right.

But each observed event is random. You can’t predict one from the other; you can only extract it from the record by observing both particles and comparing the results. So if your soul is directing your body’s choices, we could only tell by recording all the particles of your body and soul and comparing them.

Good luck with that.

The second kind of “free will” is instantaneous will: the idea that “I”, at any instant of time, could have chosen to do something differently. It’s unlikely we have this kind of free will. First, according to Einstein, simultaneity has no meaning for physically separated events – like the two hemispheres of your brain.

But, more importantly, the idea of an instant is just that – an idea. Humans are extended over time and space; the brain is fourteen hundred cubic centimeters of goo, making decisions over timescales ranging from a millisecond (a neuron fires) to a second and a half (something novel enters consciousness.)

But, even if you accept that we are physically and temporally extended beings, you may still cling to – or reject – an idea of free will: sovereign will, the idea that our decisions, while happening in our brains and bodies, are nevertheless our own. The evidence is fairly good that we have this kind of free will.

Our brains are physically isolated by our skulls and the blood-brain barrier. While we have reflexes, human decision making happens in the neocortex, which is largely decoupled from direct external responses. Even techniques like persuasion and hypnosis at best have weak, indirect effects.

But breaking our decision-making process down this way sometimes drives people away. It makes religious people cling to the hope of undetermined will; it makes scientific people erroneously think that we don’t have free will at all, because our actions are not “ours”, but are made by physical processes.

But arguing that “because my decisions are made by physical processes, therefore my decisions are not actually mine” requires the delicate dance of identifying yourself with those processes before the comma, then rejecting them afterwards. Either those decision making processes are part of you, or they are not.

If they’re not, please go join the religious folks over in the circle marked “undetermined will.”

If they are, then arguing that your decisions are not yours because they’re made by … um, the decision making part of you … is a muddle of contradictions: a mix of equivocation (changing the meaning of terms) and a category error (mistaking your decision making as something separate from yourself).

But people committed to the non-existence of free will sometimes double down, claiming that even if we accept those decision making processes as part of us, our decisions are somehow not “ours” or not “free” because the outcome of our decision making process is still determined by physical laws.

To someone working on Markov decision processes – decision machines – this seems barely coherent.

The foundation of this idea is sometimes called Laplace’s demon – the idea that a creature with perfect knowledge of all physical laws and particles and forces would be able to predict the entire history of the universe – and your decisions, so therefore, they’re not your decisions, just the outcome of laws.

Too bad this is impossible. Not practically impossible – literally, mathematically impossible.

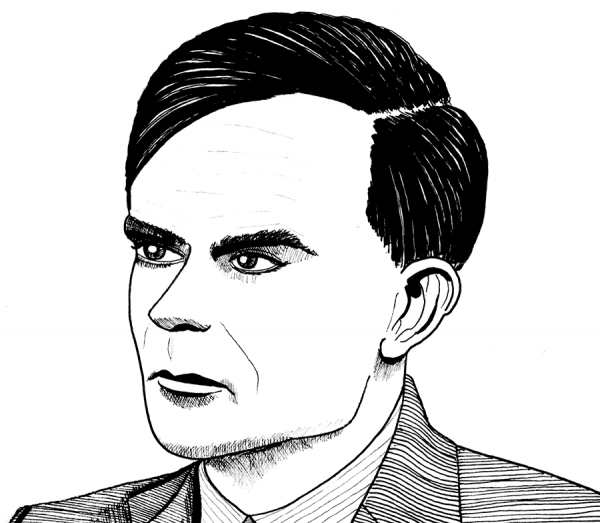

To see why, we need to understand the Halting Problem – the seemingly simple question of whether we can build a program to tell if any given computer program will halt given any particular input. As basic as this question sounds, Alan Turing proved in the 1930’s that this is mathematically impossible.

The reason is simple: if you could build an analysis program which could solve this problem, you could feed itself to itself – wrapped in a loop that went forever if the original analysis program halts, and halts if it ran forever. No matter what answer it produces, it leads to a contradiction. The program won’t work.

This idea seems abstract, but its implications are deep. It applies to not just computer programs, but to a broad class of physical systems in a broad class of universes. And it has corollaries, the most important being: you cannot predict what any arbitrary given algorithm will do without letting the algorithm do it.

If you could, you could use it to predict whether a program would halt, and therefore, you could solve the Halting Problem. That’s why Laplace’s Demon, as nice a thought experiment as it is, is slain by Turing’s Machine. To predict what you would actually do, part of the demon would have to be identical to you.

Nothing else in the universe – nothing else in a broad class of universes – can predict your decisions. Your decisions are made in your own head, not anyone else’s, and even though they may be determined by physical processes, the physical processes that determine them are you. Only you can do you.

So, you have sovereign will. Use it wisely.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Alan Turing, of course.