One stumbling block many scientifically minded people have with accepting Christianity is the false doctrine of biblical literalism. This bad idea, that the Bible is literally true, is not compatible with the Bible’s errors in cosmology, geology, meteorology, biology, psychology or even history.

If you believe in the Big Bang – and I do, until a better scientific hypothesis presents itself – you might give some credit to the Bible for God saying “Let there be light!”. But this is a pretty thin correspondence to our modern understanding – actually, whether that understanding is religious or scientific.

Both the Big Bang theory and modern Christian theology assume the world was created from nothing – ex nihilo. But Genesis describes a formless earth, vast dark waters, and the Spirit of God hovering over them. But in Christian theology, God made Creation from the outside, in Eternity, beyond time itself.

This idea isn’t nonsense – it’s similar to the creation of spacetime out of more abstract algebraic entities in certain grand unified theories of non-commutative geometry – but it isn’t literally, in the Bible. Instead, it developed through the sincere discernment of the faith leaders Jesus asked to guide his Church.

When we project our modern sensibilities on the Bible, we easily make mistakes. A fundamentalist seeking certainty in the face of scientific advances projects a “literal” truth upon the words that simple understanding of the text supports and neither the authors nor the curators of the texts meant.

Similarly, a scientist who seeking empirically tested theoretical models projects onto the Bible something that wasn’t even conceptually present when it was written. Modern hypothesis testing wasn’t invented until the 1000’s, and didn’t crystallize until the work of Francis Bacon in the 1500’s.

Similar problems occur with the Bible’s understanding not just of cosmology, but geology, like the Flood, or meteorology, like the storehouse of wind, or biology, like the creation of animals, or psychology, like Paul’s explanations of homosexuality, or even history, like much of the Biblical history of Israel.

The discovery of a destruction layer at Jericho – and the debate about whether it fits the time frame of the fall of Jericho in the book of Joshua, which according it to radiocarbon dating, it does not – shows that the Old Testament may have some correspondence with history, but it’s loose at best.

And yet, loose correspondence to history is not no correspondence. Richard Feynman once said that uncertain phenomena are like images seen through a dirty windshield; if the image isn’t real, it will wash away as you wipe away the dirt; but the image becomes clearer as you study it, it’s a real phenomenon.

The Old Testament is muddied by age and history. But what about the New Testament? The New Testament is not filled with histories written centuries after the events they describe; it’s filled with letters and testaments written by people in the orbit of Jesus, or, in a few cases, actually knew Jesus.

Peter undoubtedly knew Jesus, and some scholars believe that he wrote the First Epistle of Peter; so we might have in this book a direct record by someone who knew Jesus; but even scholars who contest this suggest the book was written no later than 81AD, roughly fifty years after Jesus’ death.

But the letters of the Apostle Paul are more certain. At least seven of them are very likely authentic – letters written by someone alleged to have been metaphorically knocked off his horse by a revelation from God. Whether you believe that’s true or not, these letters are a window into the early Church.

This is important because of another stumbling block people have with Christianity: the Resurrection of Jesus appears to have been a late addition. The Gospel of Mark, written around 70AD, roughly forty years after Jesus’s death, originally ended with the empty tomb, with no appearances of Jesus.

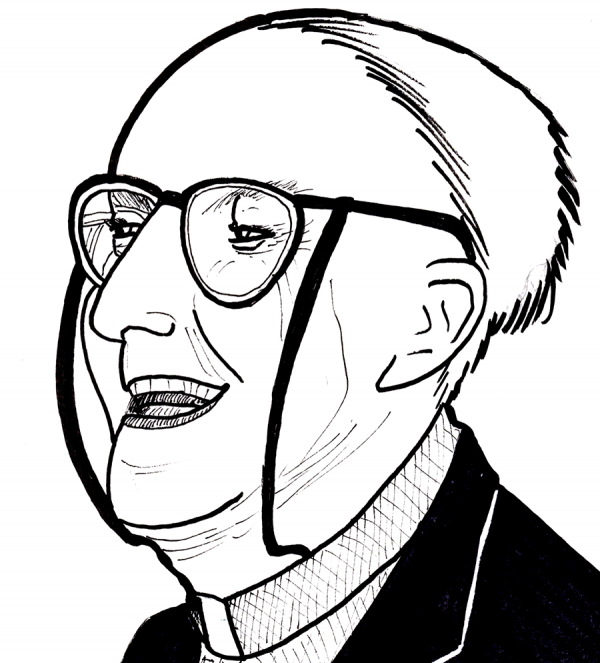

If this is the most important story about Jesus, these people ask, why is it a late addition? Seems like it was made up. But in the book Formation of the Resurrection Narratives, Reginald Fuller unpacks an even earlier and better attested First Narrative of Jesus’s Resurrection.

In First Corinthians, a letter to the church at Corinth, written by the Apostle Peter at or shortly after 53AD – only twenty years or so after Jesus’s death, we have the very First Resurrection Narrative that we know of, recorded in 15 Corinthians 3-7. It’s brief, but describes at least five appearances of Jesus:

For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins and not against all, in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also.

In his book, Fuller drills deep into these narratives, analyzing in detail the parts of this text and how it suggests, based on a textual analysis of its wording, that Paul was collating information from a variety of traditions about the appearances of Jesus and presenting them as a coherent narrative.

But what I want to drill in on is that first sentence: “For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received.” Elsewhere, Paul insists his knowledge of Jesus came from direct revelation … but here, he appears to let on that he received some information from the Christian community.

This kind of tell is used in biblical scholarship as a sign of true information. If someone’s spinning a tale to make someone look good, they often leave out the nasty bits. If someone includes some embarrassing information – like Jesus’s death, or Paul’s receipt of information – it may be a sign it really happened.

I’ll grant that Paul may have received a revelation of the divinity of Jesus on the road to Damascus. But the details of who Jesus appeared to in the community of believers at Jerusalem likely came from those believers themselves … and Paul tells us a little bit more about this in his letters as well.

In Galatians – another authentic letter of Paul’s, written in the 40’s, roughly a decade after Jesus died – Paul dates his conversion to the mid-30’s; given that Jesus died in roughly 33AD, this means Paul likely converted sometime between 34 and 36 AD – one to three years after Jesus’s death.

But Paul didn’t know Jesus when he was alive, and met Jesus in a revelation. To get at what the early Church thought, we need instead to look at what Paul describes himself as doing. In Galatians 1:18, he claims to have visited Peter in Jerusalem, three years after his conversion.

Put these things together. Less than ten years after Jesus died, Paul recounts an earlier story of meeting Peter, somewhere between 4 and 6 years after Jesus’s death. Whether Paul learned about Jesus’s post-resurrection appearances from God or Peter, at the least, Paul and Peter were on the same page.

That means the First Narrative of the Resurrection doesn’t date to twenty years after Jesus’ death: it dates to five years after Jesus’s death, and was consistent with the teachings that the community of people who knew Jesus – and Jesus’s chosen rock to found his Church, Peter.

Paul, who we believe existed, and who wrote slightly embarrassing things about himself in his letters that lead us to think they were true, describes a meeting with Jesus’s right hand man only five years after Jesus’s death, where the community was already telling stories of post-resurrection appearances.

In fact, if we believe Paul’s testimony that he’d already been preaching up to three years earlier after his conversion, and that he was proclaiming the same faith as the people he once persecuted, then these stories were already circulating in the persecuted community as early as one year after Jesus’s death.

We can use the scientific method to try to scrub away the historical inaccuracies of the Bible. We can use Christian theology to identify the true myths embedded in these recorded stories. But when we use the tools of historical analysis, there’s an image that refuses to be scrubbed away: the Resurrection.

Whether you believe in it or not, the Resurrection of Jesus – and his appearances after – are attested by the First Resurrection Narrative, and that, along with the other letters of Paul, show that the Christian community was already telling these stories within a few years – perhaps one year – after He died.

The story of the Resurrection was not a late addition: it was there from the beginning.

And it will not be scrubbed away.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Reginald Fuller.