I’m an odd fellow, spending a lot of my time (pre-pandemic) reading books and papers in nice restaurants to the bemusement of the staff, followed by writing and drawing in nice coffeehouses the hustle and bustle to drowns out everything else so I can focus on what I am doing.

While this doesn’t seem weird to me, it seems unusual enough to others that I attract the interested attention of quite a few interesting characters – some of whom frequent the same set of late-night coffeehouses, so we bump into each other again and again.

It’s through them that I got my introduction to Christian mysticism – dare I even say Christian wizardy? For someone who grew up steeped in the Roman Catholic tradition – and embedded in a deeply fundamentalist region of the Bible Belt – this mixture seems deeply weird to me.

To understand this, what we’d call “witchcraft” is proscribed in the Old Testament, which prescribes the death penalty for several forms of necromancy. In the King James Version, there’s the famous verse “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,” though my Interlinear Bible translates that as “sorceress.”

Following this tradition, many Catholics and fundamentalists view “magic and witchcraft” as literally “satanic,” which is another way of saying that they created a cute little thesaurus of suitcase words for their delusions into which they put everything that they’re scared of, like Pandora’s Box in reverse.

But there’s no “there” there, or, to make my snark a little more plain: the “magic” and “witchcraft” and “satanism” which so many Christians love to fear do not actually exist, at least not in the forms that you’ll find in a Jack Chick tract or a worried letter from St. Mary’s about the dangers of Dungeons and Dragons.

Again to be clear, it’s not that there aren’t people who believe in magic, what we might call witchcraft, and even satanism – I used to date a Wiccan, and I know several people who practice magic, some of them longtime friends – including at least one Christian “wizard” who inspired this article.

But those “practices,” if you can call them that, don’t line up with the hyperbolic and borderline delusional way Christians seem to describe them. It seems like there’s something really weird going on in the human psyche which makes people want to make up stuff about the out-group.

At one Bible study I attended, all three of my fellow students started going on about the “dangers” of “crystals” and how they were a gateway to the satanic. To my skeptical ears, this all sounded like a bunch of cosmic woo-woo, only they ascribed much more reality to it than my Wiccan friends.

One of the properties of “real” magic, if you can call it that, is that it only makes itself visible to the prepared mind. When a “practitioner” of “magick” casts a spell designed to grant them greater calm or to help them win over a colleague, only a person looking for the signs, can tell that it happened.

This is the exact opposite of the scientific method. The business science is in is getting traction – making our results, from pure mathematics to fundamental physics to applied engineering, appear reliably and repeatedly to others following unambiguous written instructions rather than mental indoctrination.

Of course, it’s not that simple. Reportedly, Faraday’s early induction experiments were very finicky, and early experimenters needed to be instructed on how to see the effects. But after a lot of development, the law today is extraordinarily reliable, part of the machinery of electromagnetism and special relativity.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that my assumptions that “crystals” are “woo” and that “magic” doesn’t “work” are just that, assumptions. (I stand by my statement that the Christian concept of “witchcraft” is not connected to reality, as magical practices are well studied in anthropology.)

Regardless of whether these Christian attitudes towards magic are real, they were pervasive when I was growing up, so much so that they heavily informed my design of the magic system of Dakota Frost, where my “skeptical witch” is also a Christian who’d rather die than make a deal with the devil.

Finding out that there are Christians who practice magic – and, we’re talking, like, hard-core Christians, people whom you’d easily mistake for an independent Baptist preacher – was therefore somewhat mindblowing. This is a sign how insular we can become if we only talk to our own in-groups.

Imagine my surprise when, at one of my favorite coffeehouses, a Vietnam veteran who I normally chatted with about Christian theology suddenly started talking about wizardry, being granted power by angels, and how he had noticed my “energy” gave off a particularly intense “aura”.

If I could sum up my friend’s theology, it would go something like this: the Bible is literally true, and we’re called on to act with humility, charity and forgiveness. But also literally true are all the conspiracy theories shared by your eccentrically religious uncle or favorite nun about vaccines or satanism or whatever.

But that’s just the surface to my friend: to him, God is really acting with grace in the world, and has sent his angels to empower people to accomplish various tasks. Christians who accept God can sometimes be given glimpses of this order, and if they choose to go down this path, may receive power.

I … am … relatively … certain this notion would have set some of my childhood fundamentalist friends on fire, right before they warned me that whoever this guy thought he was talking to, it was likely not God. But nonetheless, I can say from many conversations, the rest of this guy’s theology is spot on.

In fact, I’d really call him one of the more spiritually mature people that I’ve talked to. But nevertheless, he recommended to me several books, some of which were completely innocuous self-help books, and others like The Teachings of Don Juan by Carlos Casteneda, a book about shamanism.

My friend warned me, “You need to make sure you are spiritually prepared, mature and solid as a Christian, before you decide to go on this journey. If you go rattling the doors of reality and you aren’t properly spiritually armored, you can expect some things to come a rapping.”

Things coming a rapping? That was enough: I decided I don’t need to go on that journey. To paraphrase a character in The Blair Witch Project, if that shit isn’t real, I don’t need to go putting it in my head, and if it is real … I definitely don’t need to go putting that in my head.

My friend’s experiences are consistent with what I’ve heard from my Wiccan friends, in that getting involved in magic and spellcasting without proper guidance and preparation can open you up to spiritual attack. My fundamentalist friends would say the same thing about Tarot cards and the Ouija board.

Well, the Ouija board is a trademark of Hasbro, Incorporated, and was originally an innocent parlor game, and the Tarot itself may have developed out of an innocent game as well before it was used for divination. But one thing I’ll agree with all these friends about is the idea of spiritual attack.

C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters describe a senior devil trying to advise a junior devil on how to damn a soul – but this has precedent in Christian phenomenology, where many religious folks seem to have noticed that sometimes we seem to come under a relentless assault when we’re vulnerable.

Whether this is real or not, we do get into situations in which we are vulnerable. One of my friends, an ex-fundamentalist turned radical atheist, describes this as “the whammy”: when we’re hit by a sequence of things, each one of which we might be able to handle, but when combined, become overwhelming.

This feeling – the feeling that we can’t handle it – what Christians would call despair – is largely an illusion. If demons are real, despair is the state they seek to induce to make us make bad choices. If demons aren’t real, we’re doing this to ourselves – a state cognitive behavior therapists call catastrophizing.

Catastrophizing feels like a natural reaction to a terrible situation, but it’s really a form of self-narrative that causes us to exaggerate what’s happening to us. When we come down of that high, we feel good, not realizing that we’re reinforcing our own bad behavior.

And yet. Spiritual attack seems real. Once, while wrestling with a moral choice, I noticed a spill which took the shape of literal skull-faced demon with two giant goat horns. Now, my rational brain said, that’s likely pareidolia – seeing shapes in clouds – but the rest of me said, yeah, let’s avoid that choice, mkay?

Another time, I took a week off for my birthday, after almost a year of hard work following the death of my mother. That Friday, one of my cats had an asthma attack; the day they came home, my other cat had a urinary tract blockage; the day after I brought that cat home, the first one was back in for asthma.

I spent my whole week of vacation driving back and forth to the vet. I barely remember what happened, though I suppose I could go check the blogpost from the time. A lot was going wrong at work and at life and my wife was on the other side of the country, finishing a faux finishing job, not available to help.

The whole episode felt like a spiritual attack. I spent enough money buy a new car on what I thought was a minor vet trip. I felt like something was wearing me down. I got so physically sick I had to miss a day of work on the end of my vacation. But the truth is, I was able to deal with it.

Most of the time, human perception is based on our set level: we think we can’t handle cat-astrophes, because that situation seems so much worse than the one we’re in now; but when the cat-astrophes actually happen, we can handle them, each action following the other, one step at a time.

This is like the old story of the person walking with Jesus on the seashore, looking back to see one pair of tracks in the sand whenever life got tough; when asked why He wasn’t there when they needed them, Jesus responds, “that’s when I was carrying you.”

We may, or may not, come under real spiritual attack. But we always have a spiritual defense: turning to follow Jesus. It may feel difficult, but He’s there to help us, every step of the way. In the meantime, instead of The Teachings of Don Juan, I think I’ll stick to my Interlinear Bible.

-the Centaur

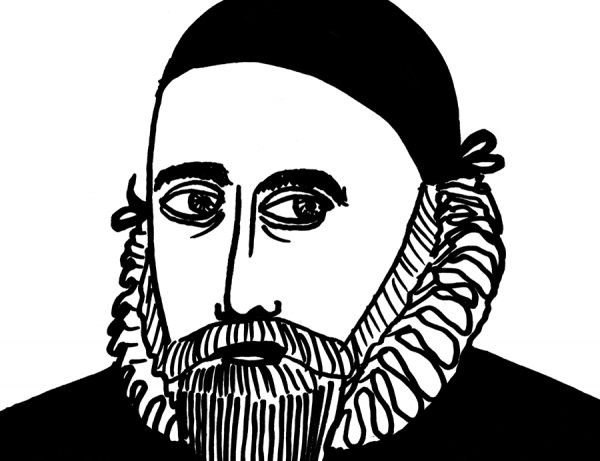

Pictured: John Dee, an occultist and also apparently a devout Christian who would be a bit baffled by the distinctions we draw today between science, magic, and religion.