Robert Heinlein famously had five rules for writing:

- Write.

- Finish what you start.

- Refrain from rewriting except to editorial order.

- Put your story on the market.

- Keep it on the market until sold.

with Robert Sawyer’s addendum’s: #6: “Start working on something else.”

Now, like all writing rules, these have limits. Take #3. Some authors write near-finished pieces on a first draft, but most don’t. I’ve done that with a very few short pieces, but most of my pieces are complex enough to require several rewrites. As you get better and better at writing, it becomes easier and easier to produce an acceptable story right off the bat … so see rule #6.

Actually, there’s a lot between rules #2 and #4. I revise a story until I feel it is ready to send to an editor … then I send it to beta readers instead, trusted confidants who can deliver honest but constructive criticism. When I feel like I’ve addressed the comments enough that I want to send it back to the betas, I don’t; I send the story out to market instead.

Regardless, some stories won’t ever sell. Many writers have a “sock drawer” of their early work (and many markets ask you not send them socks). Trying to read my first Lovecraft pastiche, “Coinage of Cthulhu,” causes me a jolt of almost physical pain. Other stories may be of an unusual length or type, and for a long odd-genre story is indeed possible to exhaust all possible markets.

So what should you do with your odd socks? Some authors, like Harlan Ellison, are bold enough to share their very early work; other authors, like Ernest Hemingway, threw away ninety nine pages for each one published. Gertrude Stein reportedly shared her notebooks almost raw; Ayn Rand reportedly rewrote each page of Atlas Shrugged five or six times. So there’s no right answer.

But again, it isn’t that simple. I recently have been reviewing my work, and while I do have a few stories likely destined for the sock drawer, and a few stories which definitely need revision, there are others that I have never sent out, especially after a low point during graduate school when I got some particularly unhelpful criticism.

Many writers are creatures with delicate, butterfly-like egos … yet you need to develop an elephant’s hide. Hemingway once said talking too much about the writers craft could destroy it, literally like brushing the scales off a butterfly’s wing; John Gardner said he’d seen far too many promising writers crushed by one too many rejections.

When a good editor (*cough* Debra Dixon, ℅ Bell Bridge Books) hits you with hard criticism on a story, she’s not trying to crush your ego: she’s trying to tell you that this character isn’t fleshed out, or the logic breaks down, or the story is dragging – or moving too fast. But not everyone’s a good editor. Not everyone’s even a good critic.

I’ve encountered far too many critics who can’t critique constructively: critics who try to be clever by turning legitimate comments into deadly bon mots; critics who try to change the story by questioning your purpose, genre or style, critics who have their own ax to grind, including one who sent me a diatribe about why I should throw out my television.

And there are friendly critics, critics who never say anything bad about your story. Some people would say you should ignore them, but I disagree. First, you need a cheerleader to feed that delicate ego you’re sheltering within that elephant’s hide; second, if even your ever chipper cheerleader doesn’t like a particular story, you better sit up and take notice.

But the stories in my low point weren’t like that. Many of them got good internal reviews, and I was happy with them, but they were long, or slipstream, and I couldn’t find markets for them. Or I was too tied up with the idea of high-paying SFWA markets. Or, more honestly, I just got busy and short shrifted them. But that opens up the question: how deep into my backlog do I go?

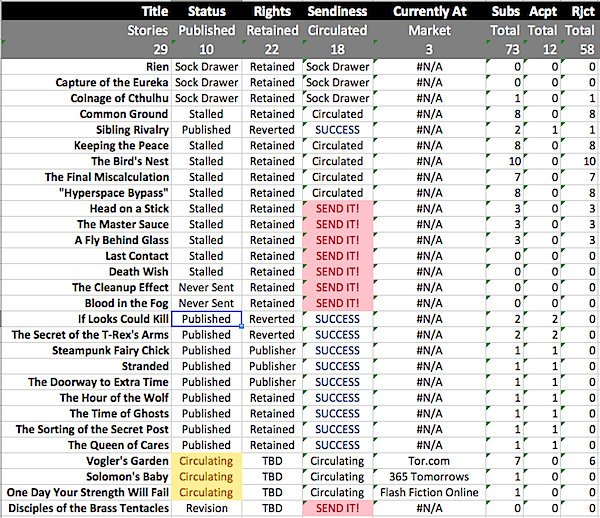

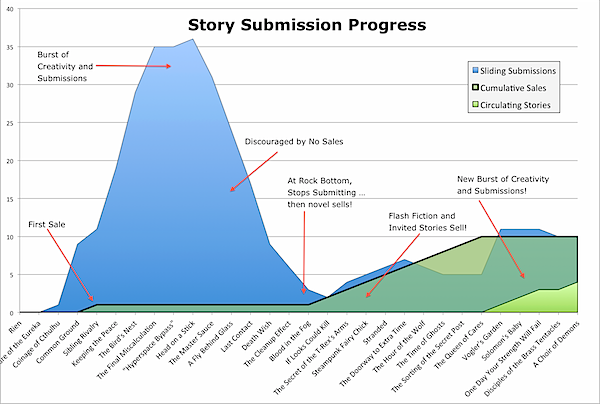

For me, answering these questions usually involves creating an Excel spreadsheet 🙂 which you see above. Clearly there was a low point in the data where I wasn’t submitting anything, and I was going to spin a story of how I got discouraged … but a closer analysis tells a different story.

The dates are approximate here, but mapping a sliding window over cumulative submissions, we can see a pattern where I started writing shorts, then had a first sale, followed by a burst of creativity on the heels of that encouragement. After a while, I got more and more discouraged, hitting rock bottom when I stopped sending shorts out at all … but this is only short story data.

Actually, I was working on a novel as well.

Before my first sale, “Sibling Rivalry”, I’d written a novel, HOMO CENTAURIS. That burst of creativity of shorts came in graduate school, when I deliberately didn’t want to take on another novel-length project. I did get discouraged, but at the same time, I started a novel, DELIVERANCE, and finished another two novels, FROST MOON and BLOOD ROCK.

FROST MOON sold right when my short story writing was picking up again. It feels like I quit, but the evidence shows that I slowly and steadily sold stories both to open markets and to invited anthologies until very recently – and that there are as many stories circulating now as I was selling earlier.

So, maybe some of these will make it. Maybe they won’t. But the data shows that feeling discouraged is pointless – my biggest sales came after my longest stretch of doggedly sending stories out. My karate teacher once said that most of your learning is on the plateau – you feel stuck, but in reality you’re learning. The data seems to bear that out.

So if I had to redo Heinlein’s rules, they’d go something like this:

- Write.

- Keep writing.

- Finish what you start.

- Circulate your work to get feedback.

- Edit your work to respond to that feedback.

- Send your edited work out to the markets.

- Don’t wait to hear back … start writing something else right away.

- Keep circulating your work until sold, or you’ve exhausted all the markets.

- No matter what happens, keep writing.

- And never, never, never give up.

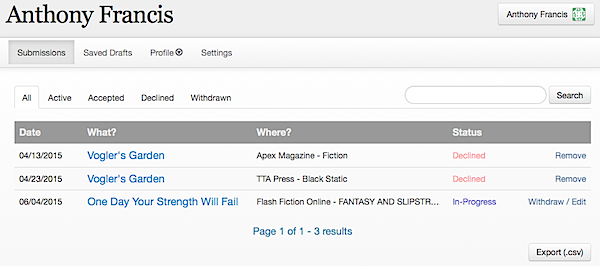

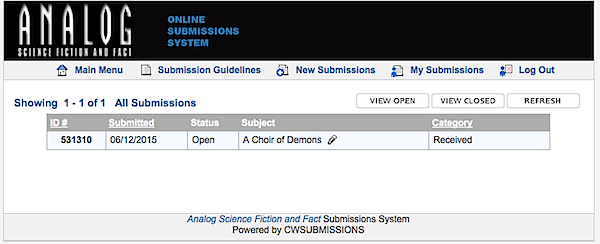

Time to practice what I preach …

…and put more stories out on the market.

-the Centaur

P.S. Axually, I’m doing a step not listed above … responding to editorial feedback on CLOCKWORK. Responding to feedback is explicit on Heinlein’s list as #3, but an implicit consequence of #8 on mine. If you sell something, listen to your editor, but keep a firm grip on your own vision. That’s hard enough it needs its own article.