So! While working on The Neurodiversiverse I’ve been reading up a lot on neurodiversity. According to Devon Price’s Unmasking Autism, autism is massively undiagnosed, and for good—well, understandable—reasons. From parents concerned about their uncommunicative children or fans of cold geniuses on Sherlock and the Big Bang Theory, our culture focuses a lot on certain stereotypes of autism—while ignoring a much larger group of people who suffer from the same underlying conditions in their brains, but who are able to “mask” their behavior to appear much more “high functioning” or even “neurotypical”.

As you might imagine, spending your whole day trying to react in ways that are fundamentally unnatural to you—and trying to hide the ways that you react that are natural to you—can stress people the fuck out. But many people never get a diagnosis—either because they’re from a disadvantaged group, or because they don’t want to risk the stigma and potential negative consequences of a diagnosis, or because they mask too well and no-on notices how they are suffering. But if you don’t understand your condition, you may employ coping strategies which may actually do more long-term harm than good.

Well, now there are a lot of online tests and self-help books and even sympathetic therapists who can help people understand themselves better. While I’ve always known I was a bit strange—mostly solitary, typically withdrawn at family gatherings when I was a child, or explicitly labeled as having a weird brain—I’ve never pursued a diagnosis of any kind—in the past, because I didn’t feel I had any trouble coping to the point that I needed help, and in the present, because having a disability label attached to you can have negative social and legal consequences that I have no interest in dealing with.

BUT! The personal stories of Unmasking Autism resonated a lot with me, and I now have friends who have gone through formal adult diagnoses of autism and ADHD, as well as an undiagnosed autistic friend who clearly is autistic and has to manage her life the way a masking autistic person does, but who did not pursue a diagnosis for precisely the same reasons that many other masking autistics do not pursue it: unless your condition is very severe, it isn’t clear that a formal diagnosis can actually get you help, and it can often get you a lot of hurt. But UNDERSTANDING it, that, that we can now do.

So! And I note I again use “So!” at the start of a paragraph. Is that a verbal tic? Who cares? SO ANYWAY …

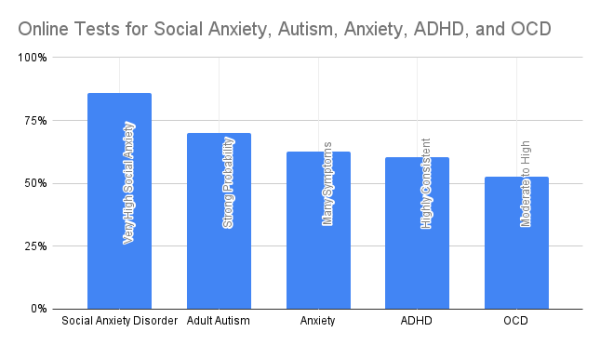

Diagnoses of autism, and other neurodivergences! The neurodivergence I identify most with is Social Anxiety Disorder—in fact, this is the neurodivergence I chose for the protagonist of “Shadows of Titanium Rain”, my own submission to The Neuroversiverse. But other people have suggested I have characteristics of OCD, or ADHD, or Autism, and I even went into therapy for stress and anxiety during the pandemic. So I decided to take five online tests: Social Anxiety Disorder, Autism, Anxiety, ADHD, and OCD.

The results are at the top of the blog—and I already gave away the game through the order I listed them. Normalizing all the scores from zero to a hundred, most of the tests put the boundary of “you’ve got the thing” at somewhere around 60-70% of the possible points you could score – let’s call it at 2/3, or 66%, shall we? OCD scored the lowest – roughly 53%, which the test judged as “you’ve got OCD tendencies, but not OCD.” ADHD was a little higher, 60%, and general Anxiety still higher, 63%. But none of these were over the “you’ve got it” thresholds for these tests—they just indicated a general tendency in that direction.

Things start to change with Autism: my test results for “Adult Autism” (*cough* MISNOMER) were 70%, well within the boundary of “you’ve very probably got it”. Some of my friends are quite surprised to hear this, as they didn’t see this in me at all; I guess my condition is “mild” and/or I mask very well.

But Social Anxiety Disorder? 86%, off the charts. And this wasn’t a surprise: not only do I have a huge raft of coping mechanisms to help me deal with social situations, I also have some of the more subtle symptoms of Social Anxiety Disorder that you might not expect would be symptoms. For example, in certain socially awkward situations, I can partially stumble while walking. Most people, even those close to me, never notice that my foot briefly drags when we’re walking and something socially awkward occurs – yet balance and coordination issues are a symptom of social anxiety.

Again, I’ve not pursued a formal diagnosis, and I don’t plan to. But understanding these things about myself helps me understand why I’ve built a mass of coping mechanisms and masking strategies in my life—and can help me start to construct a healthier way to cope with the world within which I live.

If you feel alienated by your world, perhaps that’s something you could try too.

-the Centaur