You know, Jeff Bezos isn’t likely to die when he flies July 20th. And Richard Branson isn’t likely to die when he takes off at 9am July 11th (tomorrow morning, as I write this). But the irresponsible race these fools have placed them in will eventually get somebody killed, as surely as Elon Musk’s attempt to build self-driving cars with cameras rather than lidar was doomed to (a) kill someone and (b) fail. It’s just, this time, I want to be caught on record saying I think this is hugely dangerous, rather than grumbling about it to my machine learning brethren.

Whether or not a spacecraft is ready to launch is not a matter of will; it’s a matter of natural fact. This is actually the same as many other business ventures: whether we’re deciding to create a multibillion-dollar battery factory or simply open a Starbucks, our determination to make it succeed has far less to do with its success than the realities of the market—and its physical situation. Either the market is there to support it, and the machinery will work, or it won’t.

But with normal business ventures, we’ve got a lot of intuition, and a lot of cushion. Even if you aren’t Elon Musk, you kind of instinctively know that you can’t build a battery factory before your engineering team has decided what kind of battery you need to build, and even if your factory goes bust, you can re-sell the land or the building. Even if you aren't Howard Schultz, you instinctively know it's smarter to build a Starbucks on a busy corner rather than the middle of nowhere, and even if your Starbucks goes under, it won't explode and take you out with it.

But if your rocket explodes, you can't re-sell the broken parts, and it might very well take you out with it. Our intuitions do not serve us well when building rockets or airships, because they're not simple things operating in human-scaled regions of physics, and we don't have a lot of cushion with rockets or self-driving cars, because they're machinery that can kill you, even if you've convinced yourself otherwise.

The reasons behind the likelihood of failure are manyfold here, and worth digging into in greater depth; but briefly, they include:

- The Paradox of the Director's Foot, where a leader's authority over safety personnel - and their personal willingness to take on risk - ends up short-circuiting safety protocols and causing accidents. This actually happened to me personally when two directors in a row had a robot run over their foot at a demonstration, and my eagle-eyed manager recognized that both of them had stepped into the safety enclosure to question the demonstrating engineer, forcing the safety engineer to take over audience questions - and all three took their eyes off the robot. Shoe leather degradation then ensued, for both directors. (And for me too, as I recall).

- The Inexpensive Magnesium Coffin, where a leader's aesthetic desire to have a feature - like Steve Job's desire for a magnesium case on the NeXT machines - led them to ignore feedback from engineers that the case would be much more expensive. Steve overrode his engineers ... and made the NeXT more expensive, just like they said it would, because wanting the case didn't make it cheaper. That extra cost led to the product's demise - that's why I call it a coffin. Elon Musk's insistence on using cameras rather than lidar on his self-driving cars is another Magnesium Coffin - an instance of ego and aesthetics overcoming engineering and common sense, which has already led to real deaths. I work in this precise area - teaching robots to navigate with lidar and vision - and vision-only navigation is just not going to work in the near term. (Deploy lidar and vision, and you can drop lidar within the decade with the ground-truth data you gather; try going vision alone, and you're adding another decade).

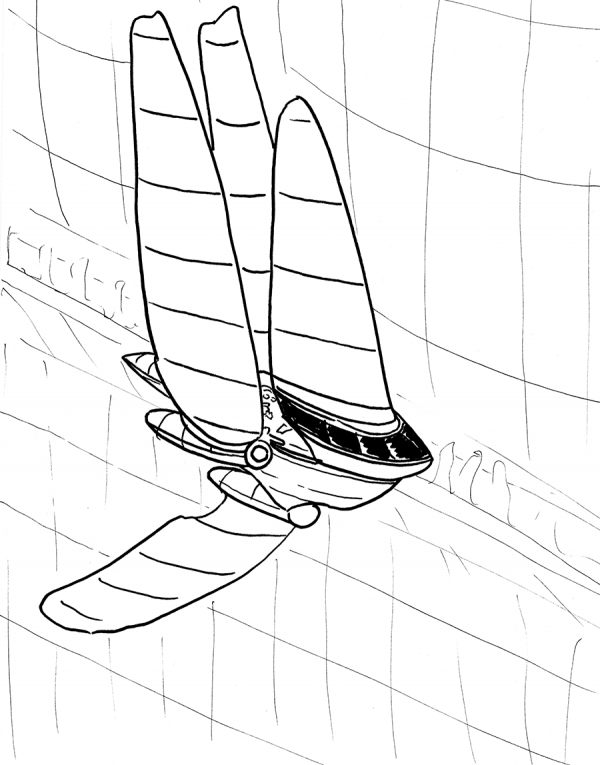

- Egotistical Idiot's Relay Race (AKA Lord Thomson's Suicide by Airship). Finally, the biggest reason for failure is the egotistical idiot's relay race. I wanted to come up with some nice, catchy parable name to describe why the Challenger astronauts died, or why the USS Macon crashed, but the best example is a slightly older one, the R101 disaster, which is notable because the man who started the R101 airship program - Lord Thomson - also rushed the program so he could make a PR trip to India, with the consequence that the airship was certified for flight without completing its endurance and speed trials. As a result, on that trip to India - its first long distance flight - the R101 crashed, killing 48 of the 54 passengers - Lord Thomson included. Just to be crystal clear here, it's Richard Branson who moved up his schedule to beat Jeff Bezos' announced flight, so it's Sir Richard Branson who is most likely up for a Lord Thomson's Suicide Award.

I don't know if Richard Branson is going to die on his planned spaceflight tomorrow, and I don't know that Jeff Bezos is going to die on his planned flight on the 20th. I do know that both are in an Egotistical Idiot's Relay Race for even trying, and the fact that they're willing to go up themselves, rather than sending test pilots, safety engineers or paying customers, makes the problem worse, as they're vulnerable to the Paradox of the Director's Foot; and with all due respect to my entire dot-com tech-bro industry, I'd be willing to bet the way they're trying to go to space is an oversized Inexpensive Magnesium Coffin.

-the Centaur

P.S. On the other hand, when Space X opens for consumer flights, I'll happily step into one, as Musk and his team seem to be doing everything more or less right there, as opposed to Branson and Bezos.

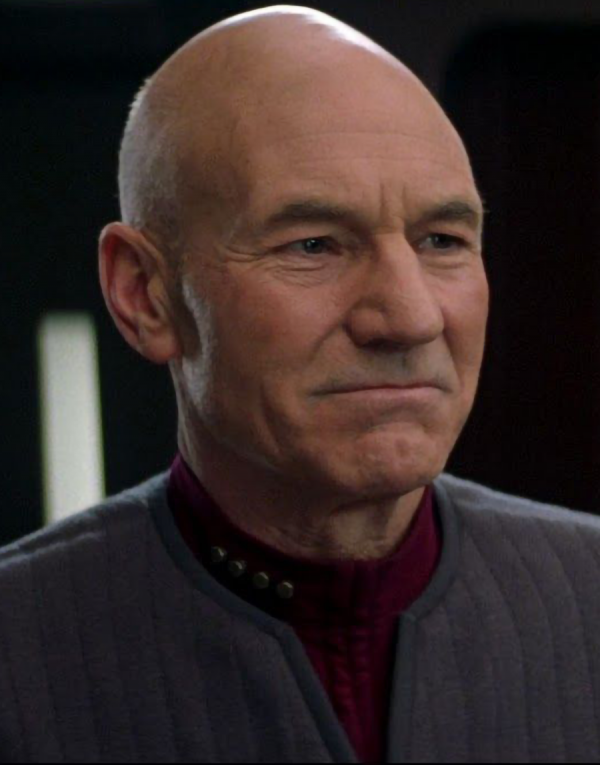

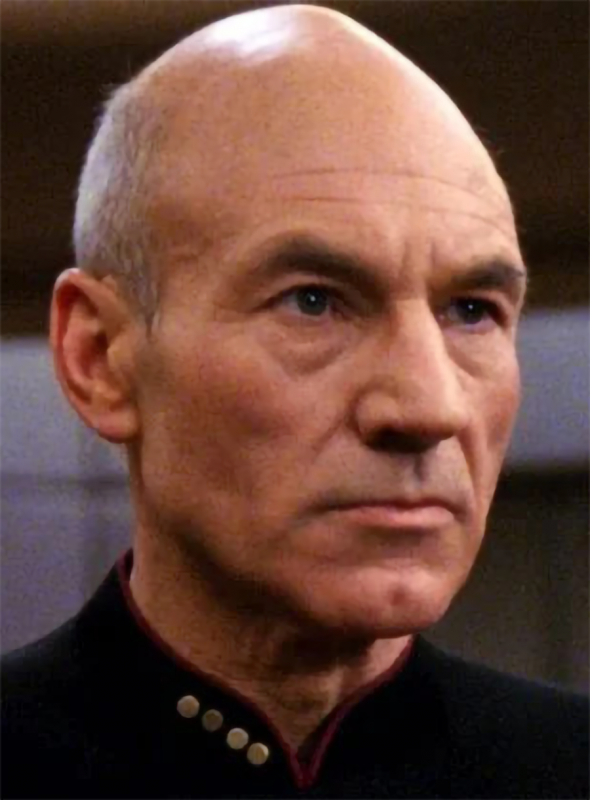

P.P.S. Pictured: Allegedly, Jeff Bezos, quick Sharpie sketch with a little Photoshop post-processing.