Back in the day, I had both a "Jesus fish" and a "Darwin fish" on the back of my car (as I recall, it was an Isuzu Rodeo, a nice car but nowhere near as reliable as my beloved Nissan Pathfinder or my seemingly unkillable Toyota Prius). I also had a "Cthulhu fish" fridge magnet which I had as a joke.

But I wouldn't have put a Cthulhu bumper sticker on my car, because the school of fish on that bumper were not a joke (though I admit I enjoyed the smidge of irony) but instead represented a sincere advertisement of my beliefs - and while it's a fun story, Cthulhu doesn't cut that mustard.

You're reading a Lenten series, so I hope it's apparent that I'm a Christian; during this series, I mentioned that once I thought of becoming an evolutionary biologist. To some Christians, these things seem hard to fit together, as many Christians are dead set on sticking to the cosmology of the Hebrews.

But the stories told in Genesis are wrong, at least as cosmology, geology, biology or history. The meaning behind the misleading Catholic term "myth" for some stories in the Bible is that stories are inspired by God and teach important truths, even if they aren't precisely accurate histories.

Despite some people's attempts to treat the Bible as a fax from God, our understanding of God has progressed since the books of the Bible were written by their authors, collated by early Christians, and ultimately approved by the early Catholic Church.

For example, the Trinity - the notion that the one (1) God manifests in three distinct "persons", Father, Son and Holy Ghost - doesn't appear directly in the Bible; we developed that understanding over time. But it's the most important Christian doctrine. You can't understand Jesus as the Son of God without it.

On the other hand, other ideas we have discarded. Even within the Bible, we see debates between sincere believers, such as the rejection of Jewish dietary rules for Gentiles in Acts of the Apostles. Doctrines like the divine right of kings and the proper treatment of slaves have been abandoned.

Now, science is familiar with this process. Some scientific ideas were bad from the get-go. The Earth was never at the center of the universe, matter isn't composed of four elements, and the motion of projectiles can't be explained by an "impulse" that slowly runs out: these ideas were never right.

Other ideas - like the Earth being round, matter being made of atoms, or light being made of waves or particles - started off right. Now, Earth isn't perfectly round, and atoms aren't perfectly indivisible, and tiny things are weirdly both waves and particles - but these ideas were on the right track from the beginning.

There's very little that science can "prove" to be true. All science is based on observation, generalization and experiment, and new experiments could show nuances that could force us to throw out our ideas - the technical term for this is "defeasible" reasoning - likely outcomes which might be true.

This is a natural outcome of the probabilistic reasoning that underlies most of our formal reasoning apparatus (and might even explain some of the inner guts of cognition as well): unless something is absolutely certain, conclusions founded on it can't be absolutely certain.

The best you can hope for, as far as proofs go, is to develop theorems of broad applicability. Physicists argue from symmetries, which enable vast regions of deduction from very few premises. Computer scientists use the theory of computation, which applies to a broad category of possible universes.

But, between our observations, our generalizations, our experiments, our theories, and our theorems, science has come up with a few things we can count on - the Earth is round, matter is made of atoms, and at the speed and scale experienced by humans, the Newtonian approximation to mechanics.

Science doesn't have definitive truths, but it is an engine for seeking it - for expanding the regions we think are probable and discarding the ideas which contradict experiment or each other. "The sole test of any idea open to observation is experiment" is the best tool we have for reaching truth - in any area.

That's why I put the Darwin fish with its cute little feet on my car: to represent the search for truth. But science is not enough. Science, by itself, is amoral: it can tell us what exists in the world, but it can't tell us what to do with it. That's where ethics, morals, religion and spirituality come in.

You can go far without invoking the supernatural. Philosophers argue that you can't go from an "is" to an "ought" - to argue from what exists to what to do about it - but this isn't quite true. Ayn Rand points out ethics are judgments about what's good for human beings, so we're not free to pick any ethics we like.

But as we discussed earlier, no individual human being experiences enough to make accurate ethical judgments on their own - nor are we guaranteed that our society has experienced enough to make our ethics accurate either. And if there really is an afterlife or a spiritual realm, experience won't cut it.

If there is a God, then we rely on Him to inform us about the spiritual dimension of the universe which either exist in the afterlife we haven't yet reached or are part of the cosmic nature of the universe which we don't have the stature to grasp. And this information - this Revelation - is therefore special.

This is the reason early Jews and Christians wrote down their experiences, and the reason the early Church collated it and preserved it. It's the reason fundamentalists treat the Bible as literally true, and the reason I treat the Bible as primary source material.

Ethics come from the spiritual dimension of the universe, and are ultimately holy. What we should do is determined by what is - and who - is behind it. Choosing the right action isn't just a good idea: it's seeking holiness - it's choosing to follow God. And that's why the Jesus fish was on my bumper.

I say "truth and holiness" - with the truth first - because truth must come first. I don't believe in Jesus because I think He's holy; I think He's holy because I believe the stories about him are true. And while parts of the Bible that are myth, to me the Gospels (and Acts) are my primary source about Jesus.

But once you understand the truth, you need to decide what to do about it. And like the cosmology of the Bible was modified by on our current understanding, there are principles in the Bible that have needed refinement as we learn more about the world. But it's important to start there, every time.

Truth, and holiness: first find out what's true, then try to do the right thing, treating the good as sacred.

-the Centaur

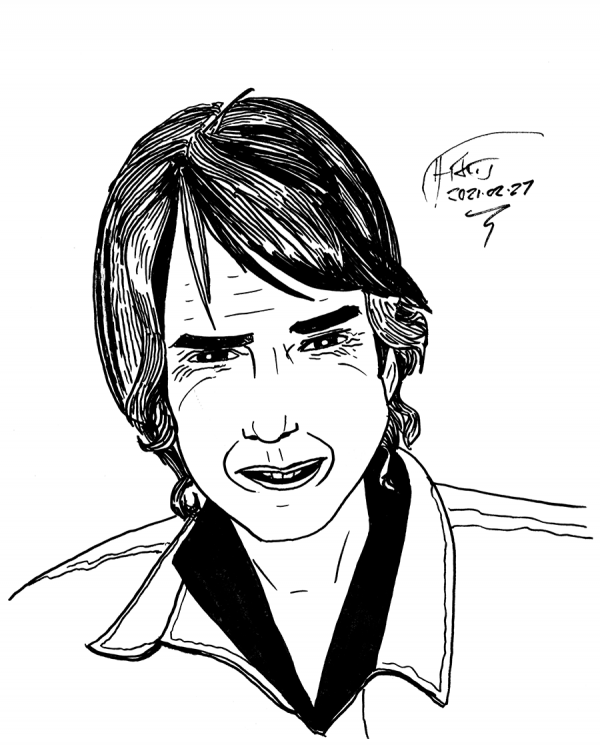

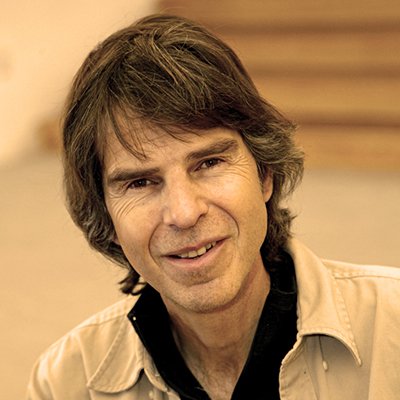

Pictured: Chuck D.

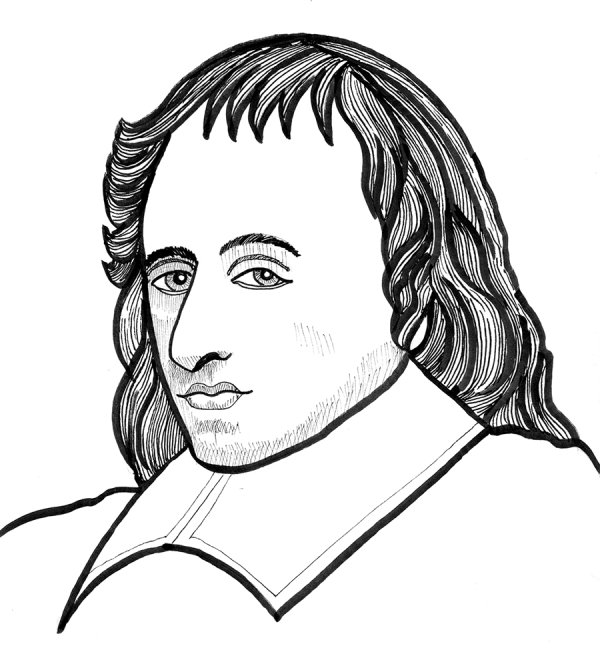

King James, a quick sketch roughed out with a 2B pencil and inked straight with a Sakura Micron 1 on the theory it's late and I'm tired. Face came out a little too tall, at least based on comparison with this detail of the original painting by John de Critz:

King James, a quick sketch roughed out with a 2B pencil and inked straight with a Sakura Micron 1 on the theory it's late and I'm tired. Face came out a little too tall, at least based on comparison with this detail of the original painting by John de Critz:

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur  Ayn Rand, roughed and inked in my usual fashion on Strathmore 9x12, No.2 pencil, Sakura Pigma and Micron pens, Sharpies for deep blacks. I squeezed the face proportions a bit, trying to get it right, and started dropping a few of my crutches on this (the heavy outlines). Again I did the trick where I turned it upside down to get the landscape right, particularly the triangle of eyes and nose; I even got the eyeline right, but failed to extend that courtesy to the mouth, which is bent a bit to the horizontal.

Nevertheless, I think, it came out pretty well: she looks so happy.

Ayn Rand, roughed and inked in my usual fashion on Strathmore 9x12, No.2 pencil, Sakura Pigma and Micron pens, Sharpies for deep blacks. I squeezed the face proportions a bit, trying to get it right, and started dropping a few of my crutches on this (the heavy outlines). Again I did the trick where I turned it upside down to get the landscape right, particularly the triangle of eyes and nose; I even got the eyeline right, but failed to extend that courtesy to the mouth, which is bent a bit to the horizontal.

Nevertheless, I think, it came out pretty well: she looks so happy.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

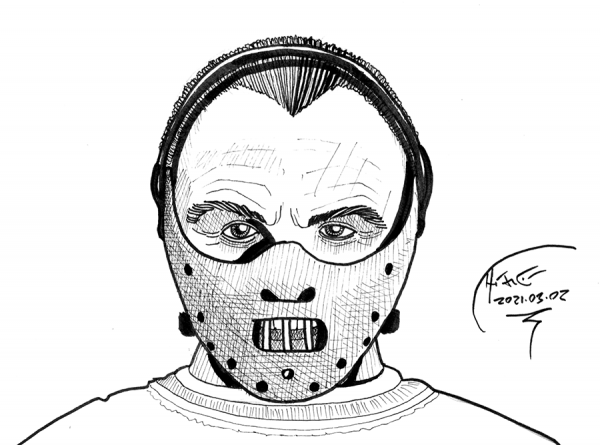

Hannibal Lecter, sketched on Strathmore 9x12 in #2 pencil followed by inking via Sakura Micron and Pigma pens. I think this one turned out pretty well, though the eyes are a tad less symmetrical than Sir Anthony Hopkins, eyebrows too far, and a few subtle details of the collar and mask aren't quite right.

Hannibal Lecter, sketched on Strathmore 9x12 in #2 pencil followed by inking via Sakura Micron and Pigma pens. I think this one turned out pretty well, though the eyes are a tad less symmetrical than Sir Anthony Hopkins, eyebrows too far, and a few subtle details of the collar and mask aren't quite right.

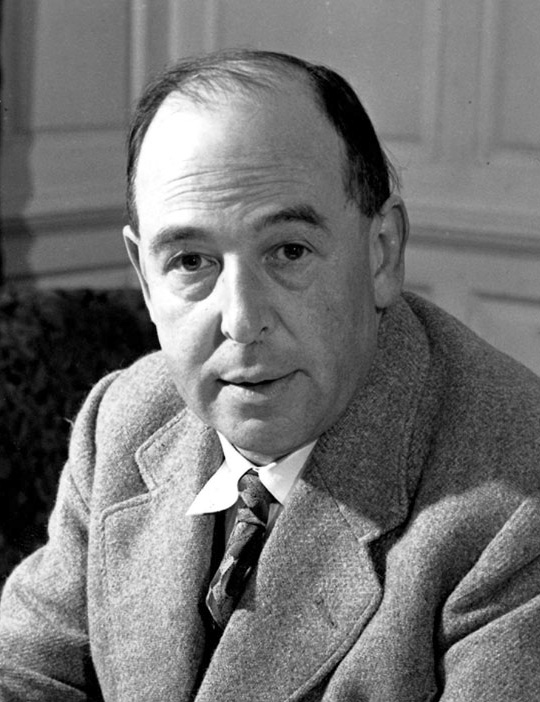

C. S. Lewis, same medium as Lecter. His face came out a bit bloated, I think - probably, I rushed it since it was late. Nevertheless, spinning the picture 180 still helped how it came out quite a bit.

C. S. Lewis, same medium as Lecter. His face came out a bit bloated, I think - probably, I rushed it since it was late. Nevertheless, spinning the picture 180 still helped how it came out quite a bit.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

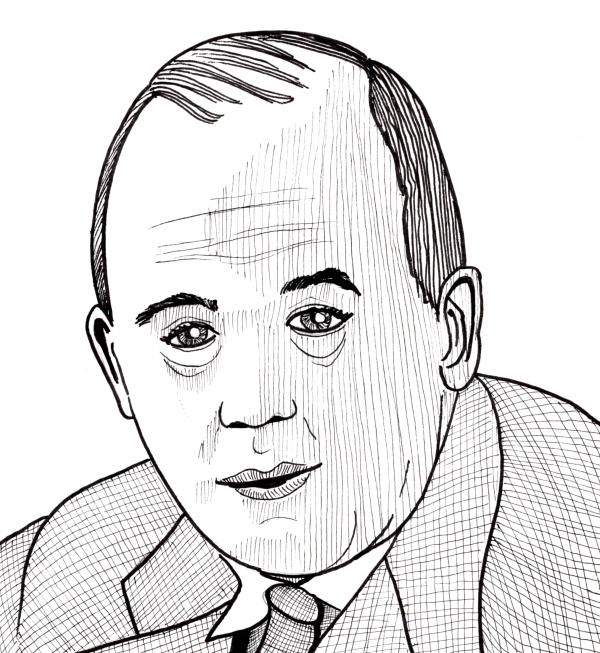

Blaise Pascal, roughed on Strathmore 9x12 with a 2B pencil (upside down to get the shapes right) and inked with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. Forehead's a little off, slightly too big compared to the drawing; the left eye is not bent downward in the same way; actually, it seems like I squeezed that in a bit as I've been doing on some other drawings. In all fairness to myself, I actually increased the size of his head on purpose, as many older paintings seem to collapse the head a bit, and I didn't bend the left eye down, as I didn't see that distortion in any of the other paintings I could find of Pascal.

Blaise Pascal, roughed on Strathmore 9x12 with a 2B pencil (upside down to get the shapes right) and inked with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. Forehead's a little off, slightly too big compared to the drawing; the left eye is not bent downward in the same way; actually, it seems like I squeezed that in a bit as I've been doing on some other drawings. In all fairness to myself, I actually increased the size of his head on purpose, as many older paintings seem to collapse the head a bit, and I didn't bend the left eye down, as I didn't see that distortion in any of the other paintings I could find of Pascal.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

It's late and I'm tired, so you get a quick sketch of

It's late and I'm tired, so you get a quick sketch of  Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur

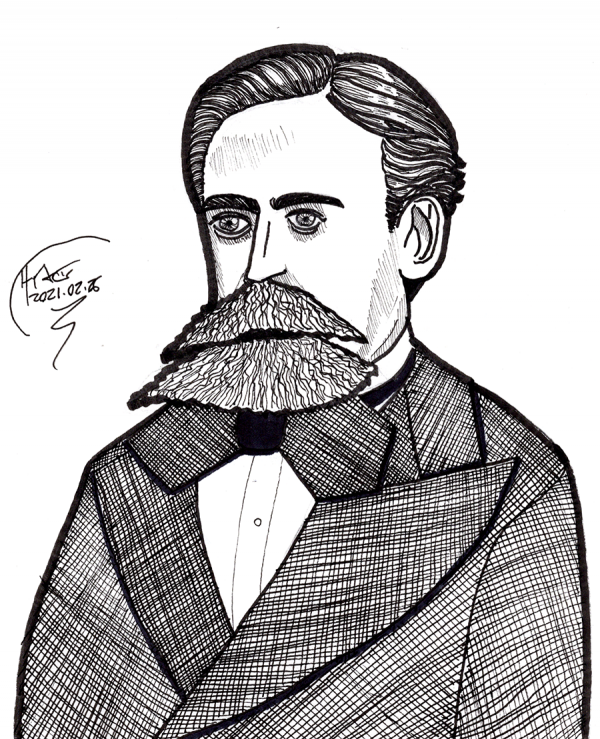

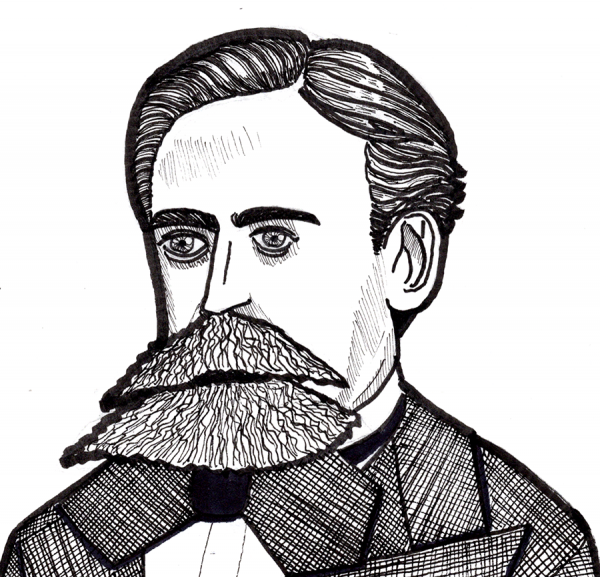

Andrey Markov, roughed with a 2B pencil on Strathmore 9x12. I then rotated the drawing and the reference photo 180 to correct errors, over a couple of quick passes, before inking directly on the paper with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. Not completely terrible, but I still need to practice drawing eyes.

Andrey Markov, roughed with a 2B pencil on Strathmore 9x12. I then rotated the drawing and the reference photo 180 to correct errors, over a couple of quick passes, before inking directly on the paper with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. Not completely terrible, but I still need to practice drawing eyes.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

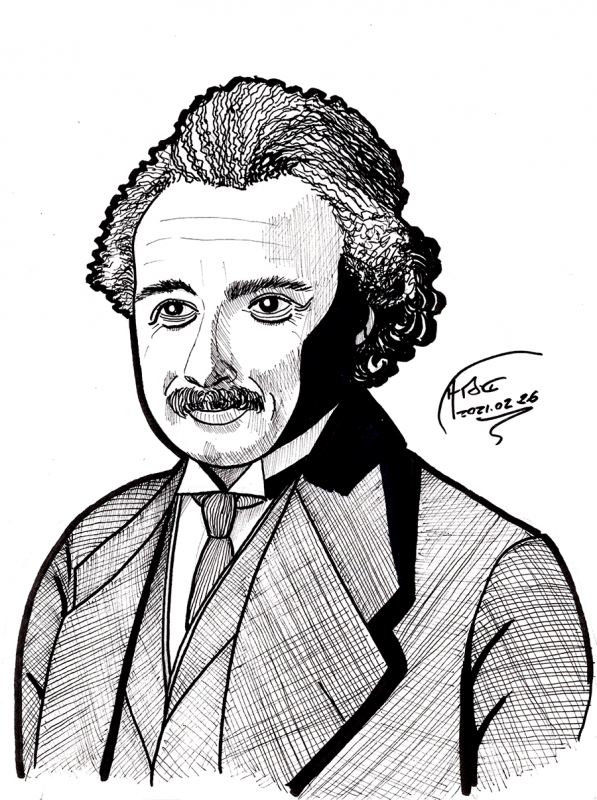

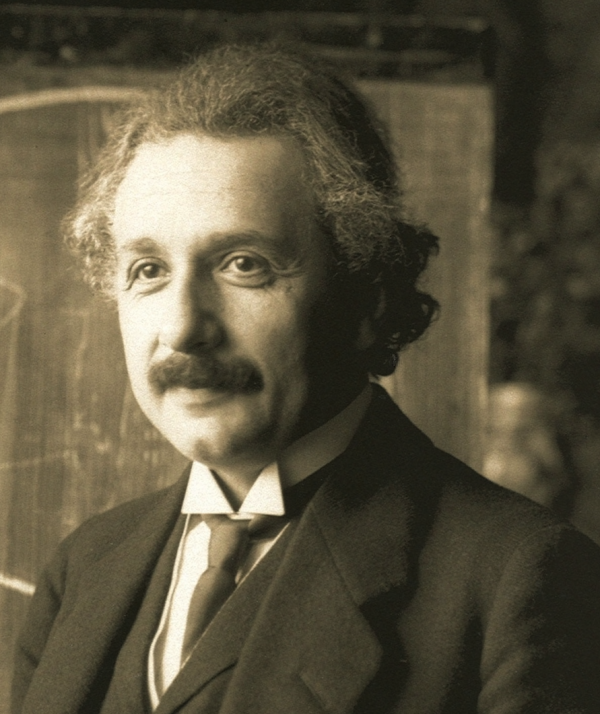

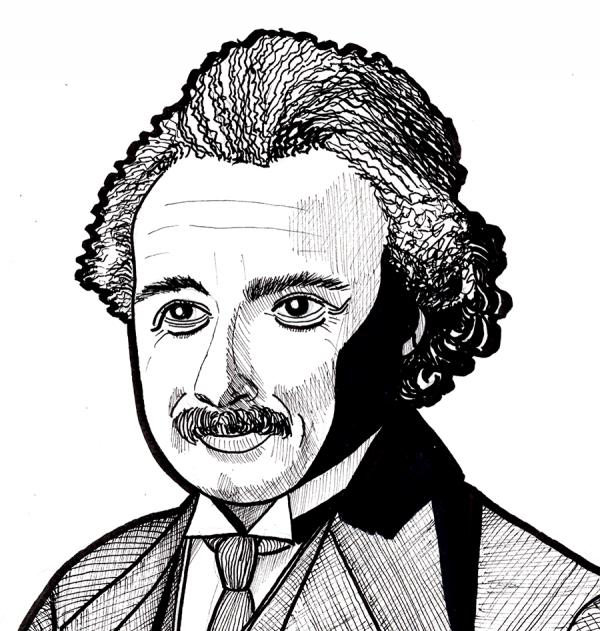

Einstein on Strathmore 9x12. First roughed with a #2 pencil, again using the trick of rotating it 180 so that I could force myself to see and draw what was there, not a caricature of a face. This came out good enough that I half-erased it, finessed the lines, and half-erased again, tightening up, before inking with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. As for whether the face looks like a face ...

Einstein on Strathmore 9x12. First roughed with a #2 pencil, again using the trick of rotating it 180 so that I could force myself to see and draw what was there, not a caricature of a face. This came out good enough that I half-erased it, finessed the lines, and half-erased again, tightening up, before inking with Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. As for whether the face looks like a face ...

... I do see things to fix, but I am not so unhappy with this one. I put special focus on the relative position, shape, and direction of the eyes, and cross-correlated with the mustache, hair and ears; a few more tweaks to the eyes, eyebrows and lip direction, plus the eye direction, really brought out the smile.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

... I do see things to fix, but I am not so unhappy with this one. I put special focus on the relative position, shape, and direction of the eyes, and cross-correlated with the mustache, hair and ears; a few more tweaks to the eyes, eyebrows and lip direction, plus the eye direction, really brought out the smile.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

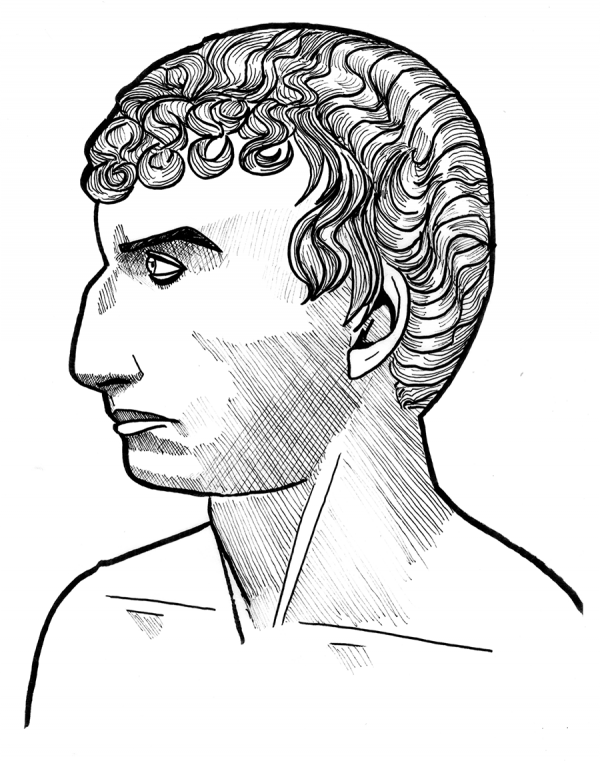

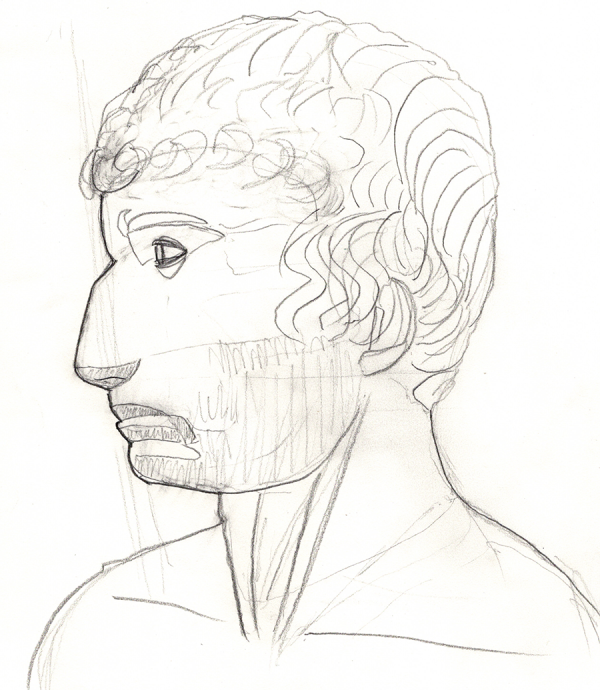

A sketch of Josephus the historian on tracing paper using Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. I started sketching with a Winsor-Newton 2B pencil on Strathmore, but the face wasn't coming out quite right. To correct it, I opened Google Meet - yes! - which mirror-reflects the images it presents of yourself (so you see what you normally see in a mirror and aren't weirded out). I already had Josephus's bust up in a Preview window, so I mirror-reflected that horizontally and compared them, trying to make fixes.

Mirror reflecting a drawing helps you see flaws in it, and that helped, but on the fine details of the face, it's really hard for me to draw things like lips and noses as what is there, rather than what my mind caricatures, so I eventually flipped the drawing back to normal and rotated it 180, so I would not see the stereotypes and instead had to focus on the shapes.

And when I was done with all that, I decided that it was still off, and I needed to start over.

A sketch of Josephus the historian on tracing paper using Sakura Pigma and Micron pens. I started sketching with a Winsor-Newton 2B pencil on Strathmore, but the face wasn't coming out quite right. To correct it, I opened Google Meet - yes! - which mirror-reflects the images it presents of yourself (so you see what you normally see in a mirror and aren't weirded out). I already had Josephus's bust up in a Preview window, so I mirror-reflected that horizontally and compared them, trying to make fixes.

Mirror reflecting a drawing helps you see flaws in it, and that helped, but on the fine details of the face, it's really hard for me to draw things like lips and noses as what is there, rather than what my mind caricatures, so I eventually flipped the drawing back to normal and rotated it 180, so I would not see the stereotypes and instead had to focus on the shapes.

And when I was done with all that, I decided that it was still off, and I needed to start over.

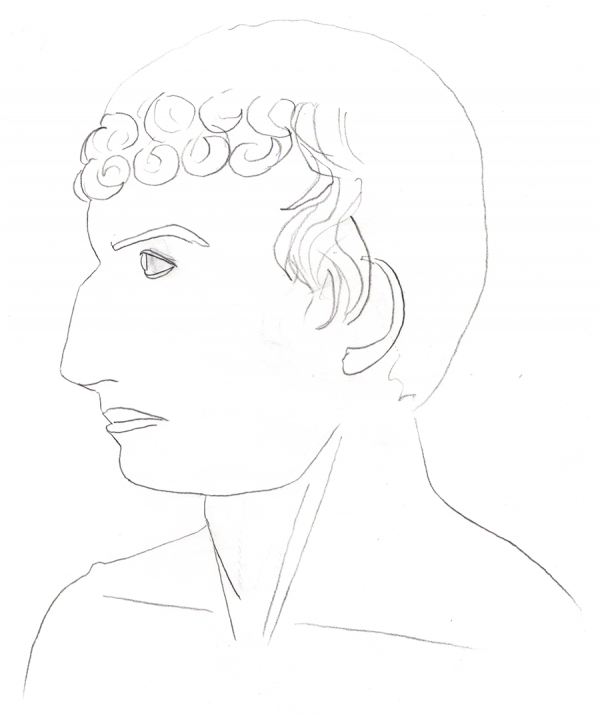

Since it's late and I'm tired, I pulled out my tracing paper and attempted to correct the drawing by tracing over my own roughs, below. The advantage of this approach is that I can change anything, or even neglect to trace something which was done correctly on the previous level, so, best of both worlds. I think I did pretty OK, though I had not noticed that I'd exaggerated the vertical height of his nose.

Since it's late and I'm tired, I pulled out my tracing paper and attempted to correct the drawing by tracing over my own roughs, below. The advantage of this approach is that I can change anything, or even neglect to trace something which was done correctly on the previous level, so, best of both worlds. I think I did pretty OK, though I had not noticed that I'd exaggerated the vertical height of his nose.

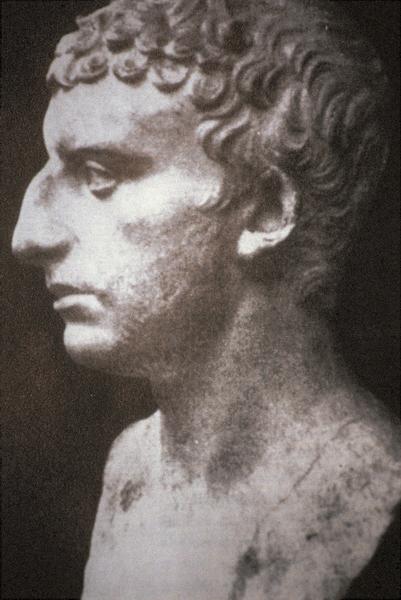

Compared to the original ... well, yeah, Josephus has a heck of a schnoz, but I made it like 10-15 percent too tall, and missed the straight line on the hair on the bottom back of his head.

Compared to the original ... well, yeah, Josephus has a heck of a schnoz, but I made it like 10-15 percent too tall, and missed the straight line on the hair on the bottom back of his head.

Otherwise, a ... not completely terrible rendition?

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Otherwise, a ... not completely terrible rendition?

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur