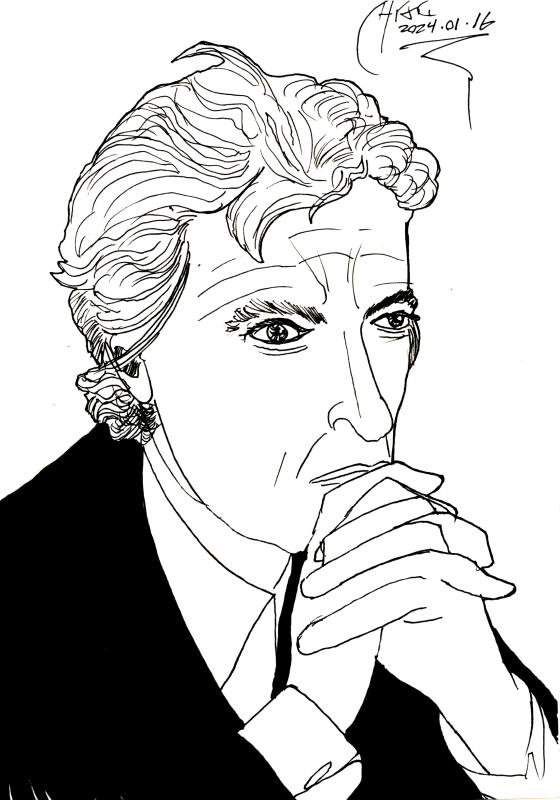

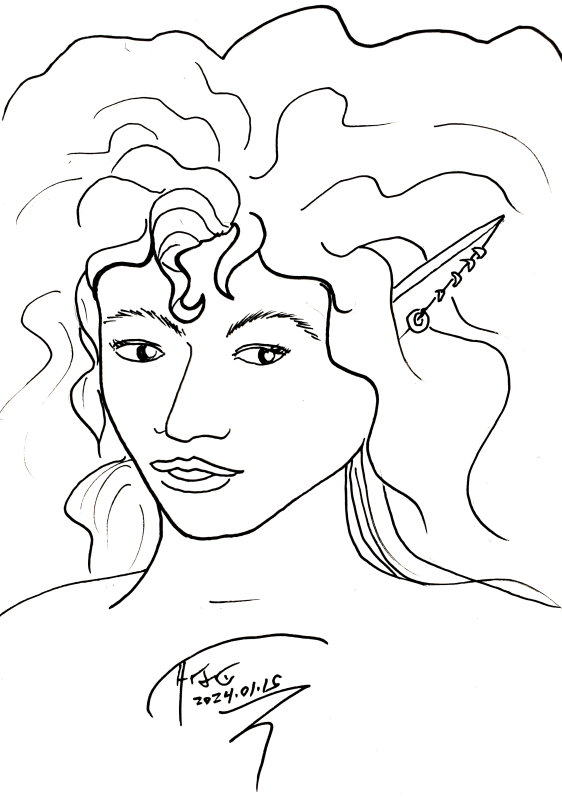

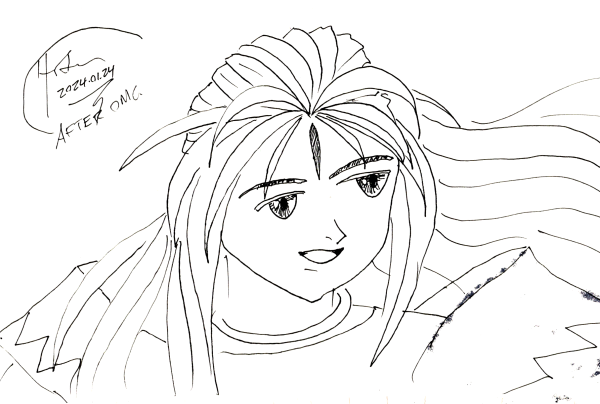

I had a somewhat ruined piece of paper, not a lot of time, and there was an image of Belldandy from Ah My Goddess on my computer's screen saver, so I decided to draw that. Unfortunately, the screen saver kept changing, and even though there were several pictures of characters from the franchise, I couldn't quite keep the image straight.

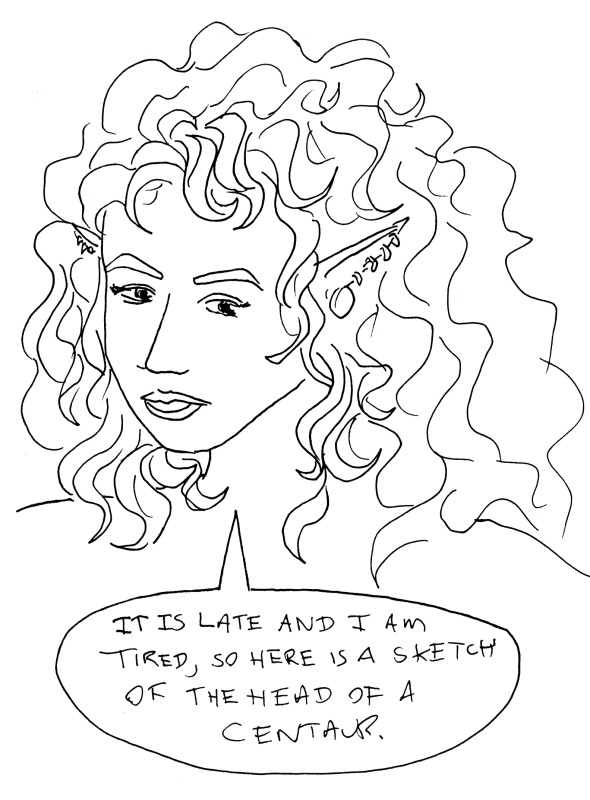

Ah well, it's late, I'm tired, scan and send - keep drawing daily, no matter what.

Don't break the streak.

-the Centaur