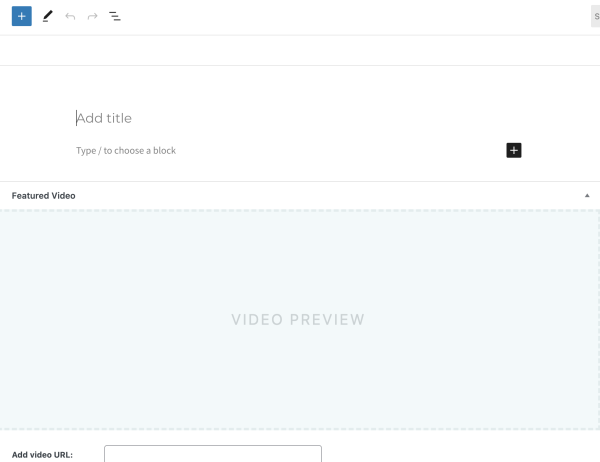

SO! My Facebook AND my credit card were both hacked within the last few months, so I was understandably freaked when I logged into the Library the other day and got a security warning. This SSL warning sometimes shows up when your network configuration changes - or when someone is trying to hack you - so I got off the conference network and used my phone's mobile hotspot. Unfortunately both the Library's WordPress control panel AND the main page showed the error, and I got a sinking feeling. Credit card got hacked a few months back, remember? And when I checked the certificate ... it had just expired.

Assuming that whatever service I use for SSL had expired due to that credit card issue, I tried to track it down in the WordPress control panel, but pretty quickly decided that digging through notes, credit cards and passwords in a public conference hall was one lapse in opsec too far. Later that night, I tried resolving the SSL issue, but found that something was wrong with the configuration and it couldn't update itself. Exhausted after a long day at the convention, I decided to get up early and attack the problem fresh.

The next morning, I found I had apparently set up WordPress to use an SSL tool which didn't play nice with my hosting provider. (I'm being deliberately vague as y'all don't need to know all the details of how my website is set up). Working through the tool's wizard didn't help, but their documentation suggested that I probably needed to go straight to the provider, which I did. After digging through those control panels, I finally found the SSL configuration ... which was properly set up, and paid through 2025.

WAT?

I re-logged into the control panel. No SSL warning. I re-opened the website. No SSL warning. I doublechecked on both another browser and another device. Both listed the site as secure.

As best as I can figure, yesterday afternoon, I hit the website in the tiny sliver of time between the old certificate expiring and the new one being installed. If I was running such a system, I'd have installed it an hour early to prevent such overlaps, but perhaps there's a technical or business reason not to do that.

Regardless, the implementation details of the "website is secure" abstraction had leaked. This is a pervasive but deceptively uncommon problem in all software development. Outside the laws of physics proper, there are no true abstractions in reality - and our notions of those laws are themselves approximations, as we found out with Einstein's tweaks to Newton's gravity - so even those laws leak.

Even a supposedly universal law, like the second law of thermodynamics that Isaac Asimov was fond of going on about, is actually far subtler than it first looks, and actually it's even subtler than that, and no wait, it's even subtler than that. Perhaps the only truly universal law is Murphy's - or mathematical ones.

Which brings us to the abstractions we have in software. In one sense, they're an attempt to overcome the universal growth of entropy, in which case they're doomed to ultimately fail; and they create that order with a set of rules which must be either incomplete or incorrect according to Godel's Incompleteness Theorem, which means they'll ultimately either fall short or get it wrong.

When developing and maintaining software - or deploying it and managing it in production - we always need to be on the lookout for leaky abstractions. We may think the system we're working with is actually obeying a set of rules, but at any time those rules may fail us - sometimes spectacularly, as in when my backup hard drive and internet gateway were struck by lightning, and sometimes almost invisibly, as in when a computer gets in a cruftly state with never-before-seen symptoms that cannot be debugged and can only be dismissed by a restart.

So my whole debugging of the SSL certificate today and yesterday was an attempt to plug a leak in an abstraction, a leak of errors that created the APPEARANCE of a long-term failure, but which was ACTUALLY a transient blip as an expired certificate was swapped out for its valid replacement.

What's particularly hard about leaky abstractions, transient failures and heisenbugs is that they train us into expecting that voodoo will work - and consciously trying to avoid the voodoo doesn't work either. On almost every Macintosh laptop I've used that has had wireless networking, it can take anywhere from a few seconds to a minute for a laptop to join a network - but once, I had the unpleasant experience of watching a senior Google leader flail for several minutes trying to get onto the network when I had to loan him my laptop to present in a meeting, as he kept switching from network to network because he was convinced that "if the network we're trying to join is working, it should immediately connect." Well, no, that would be nice, but you're sending bits over the fucking air like it was a wire, and connection failures are common. This was a decade and a half ago, but as I recall I eventually convinced him - or he got frustrated enough - to stop for a moment, after which the laptop finally had a chance to authenticate and join the network.

Debugging software problems requires patience, perseverance - but also impatience, and a willingess to give up. You need to dig into systems to find the root cause, or just try things two or three times, or turn the damn thing off and on again - or, sometimes, to come back tomorrow, when it's mysteriously fixed.

-the Centaur

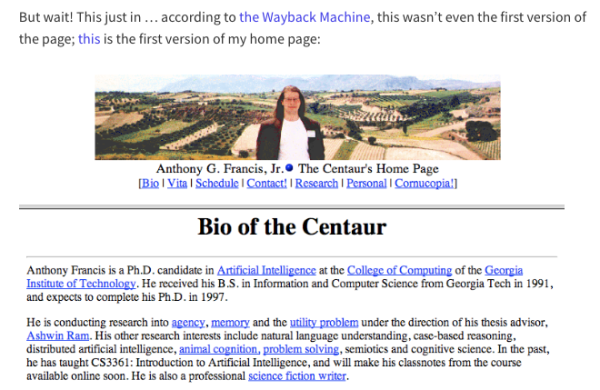

Pictured: a blurry shot of downtown San Francisco, where the abstraction of taking a photo is leaking because of camera movement, and the same intersection, with less leakage from motion.