Spent a day with my wife; enjoy this picture of a beach.

-the Centaur

Words, Art & Science by Anthony Francis

Spent a day with my wife; enjoy this picture of a beach.

-the Centaur

SO! I have no topical image for you, nor a real blogpost either, because I had a "coatastrophe" today. Suffice it to say that I'll be packing the coat I was wearing for a thorough dry cleaning (or two) when I get home, and I will be wearing the new coat my wife and I found on a Macy's clearance rack. But that replacement coat adventure chewed up the time we had this afternoon, turning what was supposed to be a two hour amble into a compressed forty-five minute power walk to make our reservation at Green's restaurant for dinner.

Well worth it, for this great vegetarian restaurant now has many vegan items; but it's late and I'm tired, and I still have to post my drawing for the day before I collapse.

Blogging every dayyszzzzz....

-the Centaur

Pictured: Green's lovely dining room, from two angles.

I really like this shot, and reserve the right to re-use it for a longer post later, yneh. But it captures the mood at the near-end of my trip to the Game Developers Conference: San Francisco, both vibrant and alive, and somehow at the same time a vaporous ghost of its former self.

Here's hoping she comes back, we miss her.

-the Centaur

SO! My Facebook AND my credit card were both hacked within the last few months, so I was understandably freaked when I logged into the Library the other day and got a security warning. This SSL warning sometimes shows up when your network configuration changes - or when someone is trying to hack you - so I got off the conference network and used my phone's mobile hotspot. Unfortunately both the Library's WordPress control panel AND the main page showed the error, and I got a sinking feeling. Credit card got hacked a few months back, remember? And when I checked the certificate ... it had just expired.

Assuming that whatever service I use for SSL had expired due to that credit card issue, I tried to track it down in the WordPress control panel, but pretty quickly decided that digging through notes, credit cards and passwords in a public conference hall was one lapse in opsec too far. Later that night, I tried resolving the SSL issue, but found that something was wrong with the configuration and it couldn't update itself. Exhausted after a long day at the convention, I decided to get up early and attack the problem fresh.

The next morning, I found I had apparently set up WordPress to use an SSL tool which didn't play nice with my hosting provider. (I'm being deliberately vague as y'all don't need to know all the details of how my website is set up). Working through the tool's wizard didn't help, but their documentation suggested that I probably needed to go straight to the provider, which I did. After digging through those control panels, I finally found the SSL configuration ... which was properly set up, and paid through 2025.

WAT?

I re-logged into the control panel. No SSL warning. I re-opened the website. No SSL warning. I doublechecked on both another browser and another device. Both listed the site as secure.

As best as I can figure, yesterday afternoon, I hit the website in the tiny sliver of time between the old certificate expiring and the new one being installed. If I was running such a system, I'd have installed it an hour early to prevent such overlaps, but perhaps there's a technical or business reason not to do that.

Regardless, the implementation details of the "website is secure" abstraction had leaked. This is a pervasive but deceptively uncommon problem in all software development. Outside the laws of physics proper, there are no true abstractions in reality - and our notions of those laws are themselves approximations, as we found out with Einstein's tweaks to Newton's gravity - so even those laws leak.

Even a supposedly universal law, like the second law of thermodynamics that Isaac Asimov was fond of going on about, is actually far subtler than it first looks, and actually it's even subtler than that, and no wait, it's even subtler than that. Perhaps the only truly universal law is Murphy's - or mathematical ones.

Which brings us to the abstractions we have in software. In one sense, they're an attempt to overcome the universal growth of entropy, in which case they're doomed to ultimately fail; and they create that order with a set of rules which must be either incomplete or incorrect according to Godel's Incompleteness Theorem, which means they'll ultimately either fall short or get it wrong.

When developing and maintaining software - or deploying it and managing it in production - we always need to be on the lookout for leaky abstractions. We may think the system we're working with is actually obeying a set of rules, but at any time those rules may fail us - sometimes spectacularly, as in when my backup hard drive and internet gateway were struck by lightning, and sometimes almost invisibly, as in when a computer gets in a cruftly state with never-before-seen symptoms that cannot be debugged and can only be dismissed by a restart.

So my whole debugging of the SSL certificate today and yesterday was an attempt to plug a leak in an abstraction, a leak of errors that created the APPEARANCE of a long-term failure, but which was ACTUALLY a transient blip as an expired certificate was swapped out for its valid replacement.

What's particularly hard about leaky abstractions, transient failures and heisenbugs is that they train us into expecting that voodoo will work - and consciously trying to avoid the voodoo doesn't work either. On almost every Macintosh laptop I've used that has had wireless networking, it can take anywhere from a few seconds to a minute for a laptop to join a network - but once, I had the unpleasant experience of watching a senior Google leader flail for several minutes trying to get onto the network when I had to loan him my laptop to present in a meeting, as he kept switching from network to network because he was convinced that "if the network we're trying to join is working, it should immediately connect." Well, no, that would be nice, but you're sending bits over the fucking air like it was a wire, and connection failures are common. This was a decade and a half ago, but as I recall I eventually convinced him - or he got frustrated enough - to stop for a moment, after which the laptop finally had a chance to authenticate and join the network.

Debugging software problems requires patience, perseverance - but also impatience, and a willingess to give up. You need to dig into systems to find the root cause, or just try things two or three times, or turn the damn thing off and on again - or, sometimes, to come back tomorrow, when it's mysteriously fixed.

-the Centaur

Pictured: a blurry shot of downtown San Francisco, where the abstraction of taking a photo is leaking because of camera movement, and the same intersection, with less leakage from motion.

The awards ceremony for the Independent Games Festival (IGF) and the Game Developers Choice Awards (GDCA) are held back to back on Wednesday nights at GDC, and I tend to think of them as "the Game Awards" (not to be confused with the other award ceremony of the same title).

The awards are always a mixture of the carefully scripted and the edgy and political, with plenty of participants calling out the industry layoffs, the war in Gaza, and discrimination in the industry and beyond. But one of those speakers said something very telling - and inspiring.

See that pillar on the right? Few people sit behind it willingly; you can't see the main stage, and can only watch the monitors. But this year's winner of the Ambassador award told the story of his first time in this hall, watching the awards from behind the pillar, wondering if he'd become a "real" game developer.

Well, he did. And won one of the highest awards in his industry.

Who knows, maybe you can too.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Top, the IGF awards. Bottom, the GDCA awards. I don't have a picture of the Ambassador Award winner because I was, like, listening to his speech and stuff.

At the Game Developer's Conference. I hope to have more to say about it (other than it's the best place to learn about game development, and has the awesome AI Summit and AI Roundtable events where you can specifically learn about Game AI and meet Game AI experts) but for now, this blogpost is to say, (a) I'm here, and (b), I'm creating some buffer so tomorrow I can write more thoughtfully.

Yeah, there are a few people here. And this isn't the half of it: it gets really big Wednesday.

Blogging every day.

-the Centaur

When you need to solve a problem, it's generally too late to learn how to solve the problem.

Contra Iron Man's assertion "I learned that last night," it's simply not possible to become an expert in thermonuclear astrophysics overnight. (In all fairness to Tony Stark, he was being snarky back to someone mocking him, when he was the only one in the room who read the briefing packet). The superintelligence of characters like Tony Stark and Reed Richards are some of the most preposterous superpowers in the Marvel Universe, because they're simply impossible to achieve: even if you ignore the fact that we can only process like 100 bits per second - and remember around 1 bit per second - and learn things in the zone of proximal development near things we already know - there's too much information in a subject like astrophysics to absorb it in the few hours of effective concentration that one could muster for a single night. Take an area I know well: artificial intelligence. A popular treatment of AI, like Melanie Mitchell's Artificial Intelligence, a Guide for Thinking Humans, is a nine hour audiobook, and drilling into a subarea is fractally just as large (a popular overview of deep learning, 8 hours - The Deep Learning Revolution; a technical overview of robotics, 1600 pages - The Springer Handbook of Robotics; and so on). You just can't learn it overnight.

So how do you solve unprecedented problems when they arrive?

You learn ahead.

If you truly need to learn something esoteric to save the world, like thermonuclear astrophysics or the correct sequence of operators for the UNIX tar command, then it's too late and you're fucked. But if you have a hint of what your future problems might be - like knowing you may need to try a generative deep learning model to help solve a learning problem you're working on - then you can read ahead on that problem before it arises. You may or may not need any specific skill that you train ahead on, but if you've got a good idea of the possibilities, you may have time to cover the bases.

Case in point: I'm working on a cover design for The Neurodiversiverse, and we're going to have to dig into font choices soon. Even though I've been doing cover design for about ten years, graphic design for about thirty years, and art for about forty-five, this is calling for a level of expertise beyond my previous accomplishments, and I'm having to stretch. When we go into the Typographidome, it will be too late to learn the features that I need to pay attention to, so I'm reading ahead by working through the third edition of Thinking With Type, which is illuminating for me all sorts of design choices that previous books simply did not give me the tools to understand. I may not need all the information in that book, but it's already given me some tools that help me understand the differences between potential font choices.

Alternately, you can work ahead.

If learning it per se isn't the problem, you may be able to do pre-work that helps you solve it. Practice, if the problem is skill or conceptual variation; or contingency planning, if the problem is potential blockers. You can't practice or plan for everything, but, again, you can cover many of the bases.

The other case in point: this entire blog post is a sneaky way to extend my blog buffer, using an idea I've already thought of to give me one more day ahead in the queue, leaving me adequate time and effort set aside to work on the series of posts that I plan to run next week. I don't know what's going to happen as I go into this interesting week of events ... but I already know that I'm going to be crunched for time, and so if I complete my "blogging every day" series ahead of time, then I can focus next week on what I need to do, instead of scrambling every day to do a task that will detract from what I need to do in that day.

So: learn ahead, and work ahead. It can save you a lot of time and effort - and avert failures - later.

-the Centaur

Pictured: a bit of Thinking with Type, Third Edition.

On the other end of the health food spectrum, we present this lovely tomahawk steak, from Chophouse 47 in Greenville. They don't even normally serve this - it was a special - but it came out extremely well (well as in excellent, not well as in well done; I had it medium rare, as it should be). And it was delicious.

Even though I can't eat them very often, I love tomahawks, as they're visually stunning and generally have the best cooked meat of any steak cut that I know.

Also, you can defend yourself from muggers with the bone.

-the Centaur

Pictured: um, I said it already, a tomahawk steak from Chophouse 47.

Thanks, mold, for making me suspicious of every new pummelo, no matter how fresh and delicious. When I have actually gotten sick off a food, sometimes I develop a lifelong aversion to it - like chili burgers, lemon bars, and pump-flavored sodas, the three things I remember eating before my worst episode of food poisoning. However, apparently finding something rotten just as you eat it is a close second.

Sigh. Here's hoping this fades.

-the Centaur

Pictured: a tasty and delicious pummelo, but even so, I can't look at them the same. Is there an evil demon face embedded in that, thanks to pareidolia?

Hey, man. Back off. I did not consent to be photographed. Geez, Louise.

As it turns out, a pair of male turkeys gobbling at each other on your front doorstep sounds a lot like two small barking dogs yapping at each other, at least when heard through the glass.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Two formerly gobbling turkeys, having noticed me trying to take a picture, hightailing it.

Cats supposedly have brains the size of a large walnut, and are not supposed to be intelligent according to traditional anthropofallicists. But there's something weird about how Loki remains perfectly still ... right up until the point where you want to take a picture, at which point he'll roll over. Or how he'll pester you, right until you're done with a task, but when you are done and can attend to him, he'll walk away.

Almost like there's something devious going on in that aloof,yet needy little brain, some thought process like, I want you to pay attention to me, but I don't want you to think that I need it.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Loki, who looked just like a sphinx, until I pulled out my camera and he immediately rolled over.

Damn you, Google Spotlight: it's a nice-sounding feature to pop up images from the past, but there's always the chance that the person or thing you pop up will be gone, and you didn't think of that, did you?

I miss you, little guy.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Gabby. No offense to any other animal I've ever owned, but Gabby was my favorite pet.

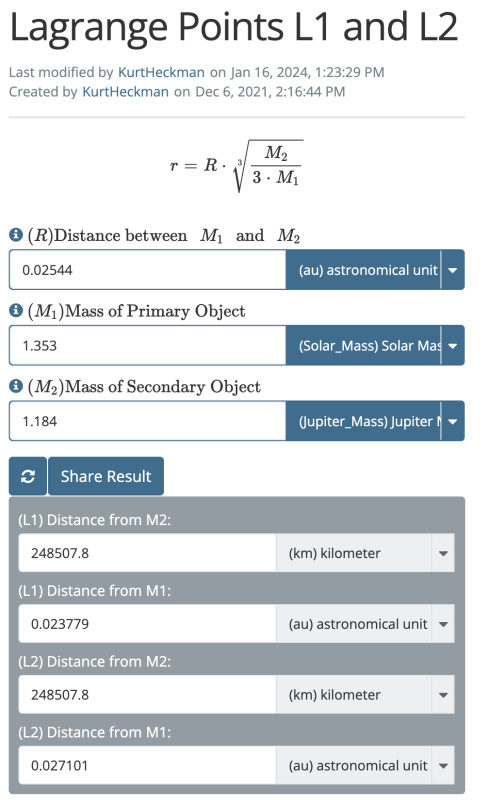

At last! Thanks to Bing, I found an online calculator whose numbers confirm the calculation I did on my own for the interplanetary distances from my story "Shadows of Titanium Rain"!

[ from https://www.vcalc.com/wiki/l1-l2-lagrange-points based on data from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WASP-121 ]

This is VERY close to the numbers I got from doing this in Mathematica based on the equations from (as I recall) the NASA page https://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/ContentMedia/lagrange.pdf :

AND, despite a good bit of reading [ https://www.amazon.com/Orbital-Mechanics-Foundation-Richard-Madonna/dp/0894640100 , https://www.routledge.com/Orbital-Motion/Roy/p/book/9781138406285 ] I was not able to find a ready source which gave me a simple formula without solving a bunch of equations.

But the calculator gave the same result that I got earlier on my own.

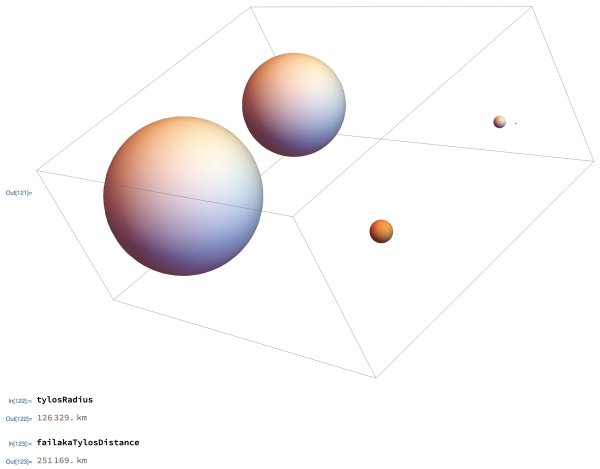

SO! Failaka is a quarter million kilometers from Tylos.

That's my story and I'm sticking to it.

-the Centaur

I can't tell you how frustrating it is for Present Anthony for Past Anthony to have set up a single place where all tax forms should go during the year, except for Past Anthony to not have used that system for the one paper form that cannot be replaced by looking it up online.

I'm sure it's here somewhere.

-the Centaur

Pictured: I have been working on taxes, so please enjoy this picture of a cat.

Unabashedly, I'm going to beef up the blog buffer by posting something easy, like a picture of this delicious Old Fashioned from Longhorn. They're a nice sipping drink, excellent for kicking back with a good book, which as I recall that night was very likely the book "Rust for Rustaceans."

Now, I talked smack about Rust the other day, but they have some great game libraries worth trying out, and I am not too proud to be proved wrong, nor am I too proud to use a tool with warts (which I will happily complain about) if it can also get my job done (which I will happily crow about).

-the Centaur

Pictured: I said it, yes. And now we're one more day ahead, so I can get on with Neurodiversiverse edits.

So, this is worthy of a longer blog post, but the short story is, looking under the streetlight for your keys may provide visibility, but it won’t help you find them unless you have reason to think that you dropped them there.

A lot of time in software development, we encounter things that don’t work, and problems like stochastic errors and heisenbugs can lead software developers to try voodoo solutions - rebooting, recompiling from head, running the build again, or restarting the server.

These “solutions” work well enough for us that it’s worthwhile trying them as a first step - several times recently I have encountered issues which simply evaporated when I refreshed the web page, restarted the server, retried the build, or restarted my computer.

But these are not actual fixes. They’re tools to clear away transient errors so we can give our systems the best chance of properly functioning. And if they don’t work, the most important thing to do is to really dig in and try to find the root cause of the problem.

On one of those systems - where I literally had tried refreshing the web page, restarting the server, refreshing the code, reinstalling the packages, and rebooting the computer - the build itself was something that you had to run twice.

Now, this is a common problem with software builds: they take a lot of files and memory, and they can get halfway through their builds and die, leaving enough artifacts for a second pass to successfully solve the problem. I had to do this at Google quite a bit.

But it isn’t a real solution. (Well, it was at Google, for this particular software, because its build was running up against some hard limits that weren’t fixable, but I digress). And so, eventually, my build for this website failed to run at all, even after a reboot.

The solution? A quick search online revealed it’s possible to change the parameters of the build to give it more memory - and once I did that, the build ran smooth as glass. The “run the build again” trick I’d learned at Google - learned where, for one particular project, it was not possible to fix the problem - had led me astray, and overapplying this trick to my new problem - where it had partial success - kept me from finding a real, permanent fix.

So, if a fix feels like voodoo, stop for a minute - and search for a better way.

-the Centaur

Pictured: What do you mean, you haven't updated the package configuration for THREE YEARS?

SO! I’ve spent more time than I like in hospitals with saline drips restoring my dehydrated blood after food-poisoning induced vomiting, and pretty much all of those episodes followed me thinking, “Huh, this tastes a little funny … ehhh, I guess it’s OK.”

That led me to introduce the following strict rule: if you think anything’s off about food, don’t eat it.

Now, that seems to make sense to most people, but in reality, most people don’t practice that. In my direct experience, if the average person gets a piece of fruit or some soup or something that “tastes a little bit funny,” then, after thinking for a moment, they’ll say “ehhh, I guess it’s OK” and chow down straight on the funny-tasting food. Sometimes they even pressure me to have some, to which I say, "You eat it."

Honestly, most of the time, a funny taste turns out fine: a funny taste is just a sign that something is badly flavored or poorly spiced or too ripe or not ripe enough or just plain weird to the particular eater. And in my experience almost nobody gets sick doing that, which is why we as humans get to enjoy oysters and natto (fermented soybeans) and thousand-year eggs (clay-preserved eggs).

But, frankly speaking, that’s due to survivor bias. All the idiots (I mean, heroic gourmands) who tried nightshade mushroom and botulism-infested soup and toxic preservatives are dead now, so we cook from the books of the survivors. And I’ve learned from unexpectedly bitter-tasting experience that if I had been a heroic gourmand back in the day, I’d have a colorful pathogen named after me.

So if anything tastes or even looks funny, I don’t eat it.

Case in point! I’m alive to write this blog entry. Let me explain.

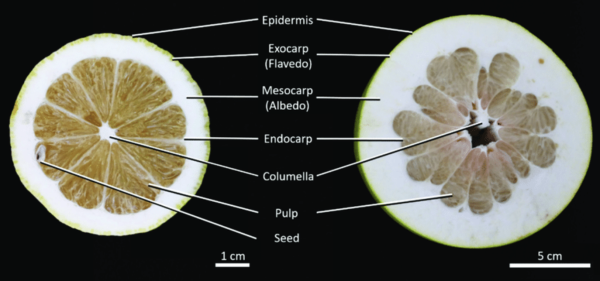

When I’m on the high end of my weight range and am trying to lose it, I tend to eat a light breakfast during the week to dial it back - usually a grapefruit and toast or half a pummelo. A pummelo is a heritage citrus that’s kind of like the grandfather of a grapefruit - pummelos and mandarins were crossed to make oranges, and crossed again to make grapefruit.

They're my favorite fruit - like a grapefruit, but sweeter, and so large that one half of a pummelo has as much meat as a whole grapefruit. I usually eat half the pummelo one day, refrigerate it in a closed container, and then eat the other half the next day or day after.

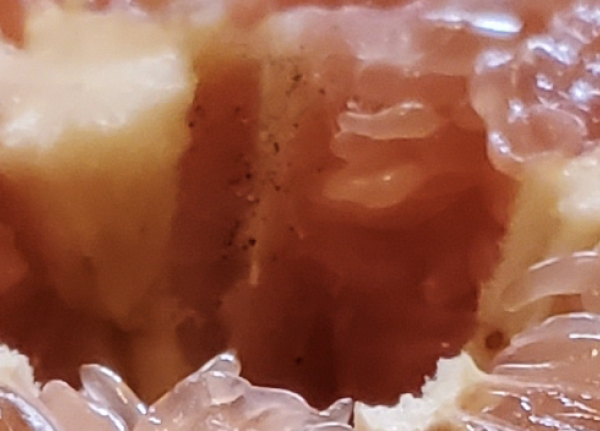

You can see this saved half at the top of the blog - it looked gorgeous and delicious. I popped into my mouth a small bit of meat that had been knocked off by an earlier cut, then picked up my knife to slice it ... when I noticed a tiny speck in the columella, the spongy stuff in the middle.

Now, as a paranoid eater, I always look on the columella with suspicion: in many pummelos, there’s so much that it looks like a white fungus growing there - but it’s always been just fruit. Figuring, “Ehh, I guess it’s OK”, I poke it with my knife before cutting the pummelo - and the black specks disappeared as two wedges of the fruit collapsed.

A chunk of this fruit had been consumed by some kind of fungus. You can kinda see the damaged wedges here in a picture I took just before cutting the fruit, and if you look closely, you can even see the fungus itself growing on the inside space. This wasn’t old fruit - I’d eaten the other half of the fruit just two days before, and it was beautiful and unmarred when I washed it. But it was still rotten on the inside, with a fungus I’ve not been able to identify online, other than it is some fungus with a fruiting body:

I spat out the tiny bit of pummelo meat I’d just put in my mouth, and tossed the fruit in the compost. But the next day, curious, I wondered if there were any signs on the other half of the fruit, and went back to find this:

Not only is the newer piece visibly moldy, its compromised pieces rapidly disintegrating, the entire older piece of fruit is now completely covered with fruiting bodies - probably spread around its surface when I cut the fruit open. From what I’ve found online, the sprouting of fruiting bodies means this pummelo had already been infested with a fungus for a week or two prior to the flowering.

So! I was lucky. Either this fungus was not toxic, or I managed to get so little of it in the first piece of fruit that I didn’t make myself sick. But it just confirms my strategy:

If it looks or tastes funny, don’t eat it.

If you don’t agree with me on a particular food, you eat it; I’m going to pass.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Um, I think I said it. Lots of pictures of bad grandpa grapefruit.

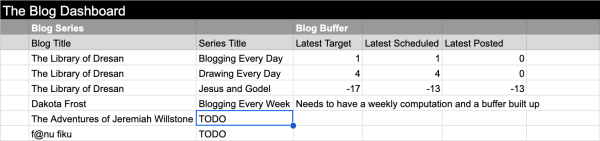

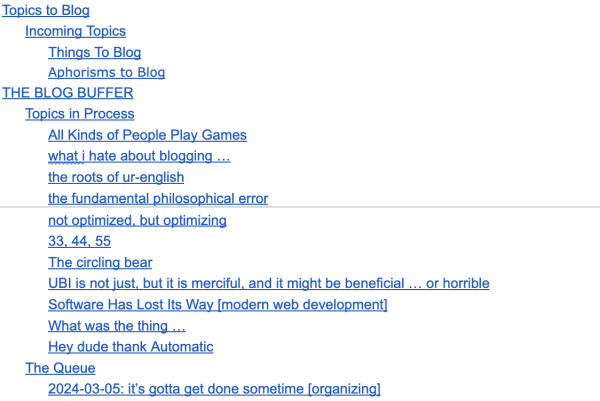

The title was supposed to say "that blog buffer" but I'm going with the misspelling. The critical thing to do with the buffers it to get far enough ahead that you can not just coast for a day or two, but take out the time to do more ambitious projects, like "fix it the way that it works" or "33 44 55", two posts that I've been putting off because I haven't been giving myself enough time to blog.

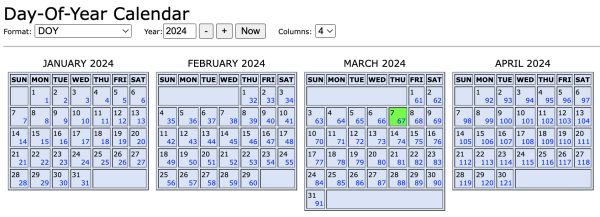

Well, according to the NOAA's day-of-year calendar, post sixty-eight needs to go up Fridya, so once I schedule this post, "the buffer" will give me until Saturday to come up with a really good idea.

I'm working on it, I'm working on it!

Blogging every day.

-the Centaur

Pictured: A few screencaps: the "The Blog Dashboard" Google Sheet, the NOAA Day of Year Calendar, and "Blog This or Code It!", the Google Doc where I dump ideas that I hope to turn into blogposts.

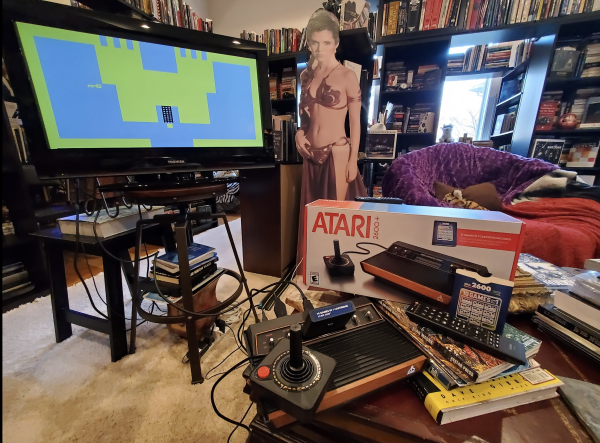

SO! I am the proud owner of ... an Atari 2600+! This console, a re-release of the original Atari 2600 from 47 (!) years ago, only a notch smaller and with USB and HDMI outputs. It plays original Atari cartridges, though, which shall be my incentive to hop on my bike and visit the retro game store in nearby Traveler's Rest which has a selection of original Atari cartridges among all their other retro games.

The first game I remember playing is Adventure, which came out in 1980, and, while I can't be sure, I seem to remember first playing it in my parents' new house on Coventry Road, which we didn't move into until early 1979, just before my birthday.

In fact, as I dig my brain into it, we played Breakout in the den of my parents's old house on Sedgefield Road, so we must have had access to early-generation Atari. Our neighbors when we moved had a snazzier Odyssey 2 :-), and a few years later another friend from school had an even better game console, though none of the second-generation units I looked up online seem familiar to me.

Therefore, by the process of elimination, either my parents got my Atari 2600 for Christmas for me sometime around 1977 or 1978, or one of our relatives or babysitters loaned us one when we lived on Sedgefield. I have distinct memories of getting a Radio Shack Color Computer in Christmas of 1980, a grey wedge of plastic with a massive 4K of RAM, and remember programming games on it myself - perhaps because I didn't have an Atari to play with; this makes me think that, at least at first, the Atari was actually the "better game console" my other friend from school had, and that I went over to their house to play.

Regardless, I solved the first level of Adventure in minutes after cracking open the Atari.

No big challenge, but apparently I still got it.

-the Centaur

Pictured: the box, and the unboxed start of Adventure.

"There's no man so self-made he bore himself in the womb."

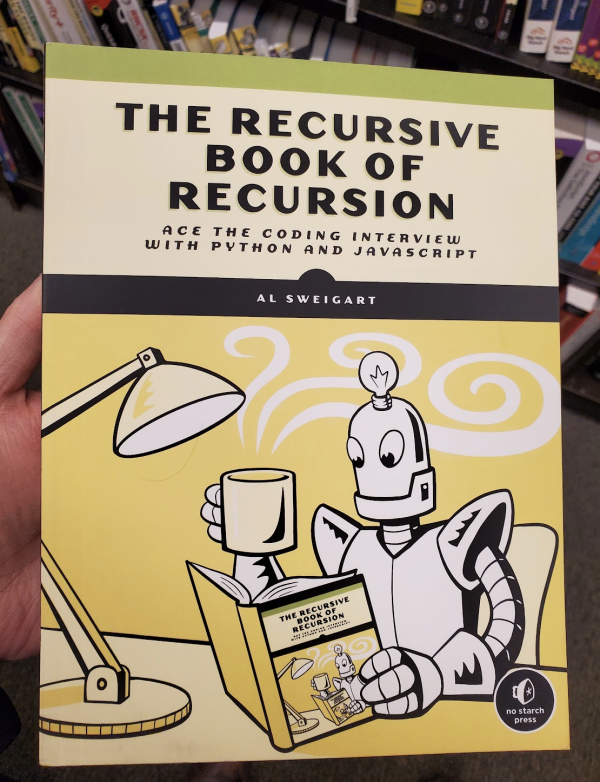

No, I don't really have any deep thoughts here riffing off "an individualist so rugged ..." ... I just thought of the turn of phrase (when thinking about the same people) and thought it went well with this book I saw.

-the Centaur

Pictured: a book I found in a nearby Barnes and Noble, and a picture taken and sent to friends who heart heart reduplication.