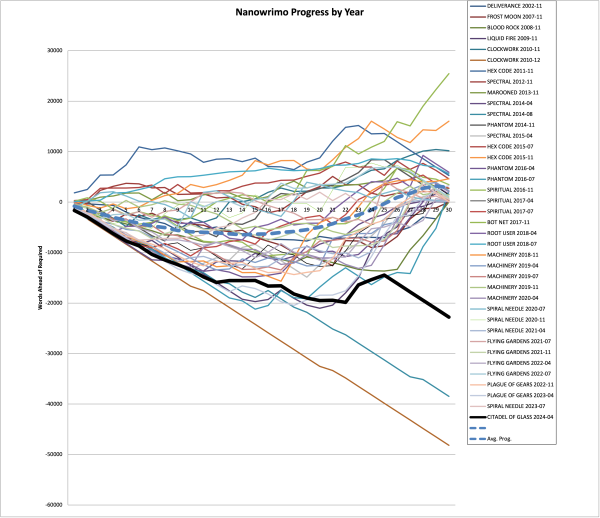

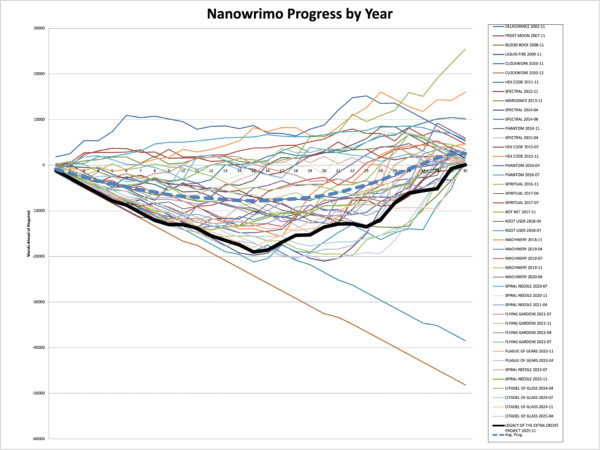

So! The National Novel Writing Month organization may be gone, but National Novel Writing Month lives on! Not just in Nano 2.0, but in my own writing. I've written two and a quarter million words in Nanos over the years, by far the bulk of my writing output, and I'm not stopping now!

For this month, my forty-fifth Nano or Nano-like challenge, I resurrected a fifteen-year-old project ... the Spookymurk! The Spookymurk is a nerfed D&D-like world - a cosy fantasy, in today's terms - which, according to my notes, I stopped work on when I got the notes back for Dakota Frost #2, BLOOD ROCK.

I had four novels come out since I first started playing with the Spookymurk, and I think that's probably a fair trade. But the story was calling to me recently - I even started drawing some of the characters as part of my Drawing Every Day project - so I resurrected Book 1: THE LEGACY OF THE EXTRA CREDIT PROJECT.

This was my forty-third successful Nano, and as always, great inventions come from the pressure that writing ~1700 words a day puts on your story. But, as I went over my old notes, I'm surprised at how extensive they were: this was a rich world, and I'm kind of sad I put it away for so long.

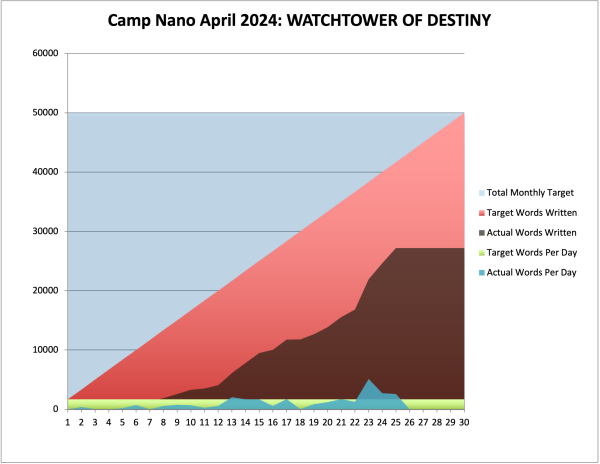

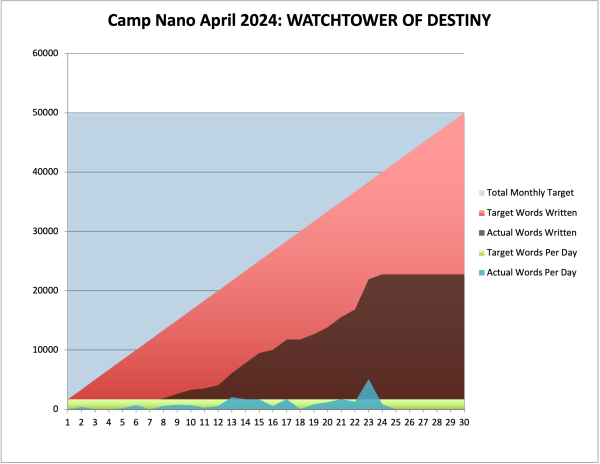

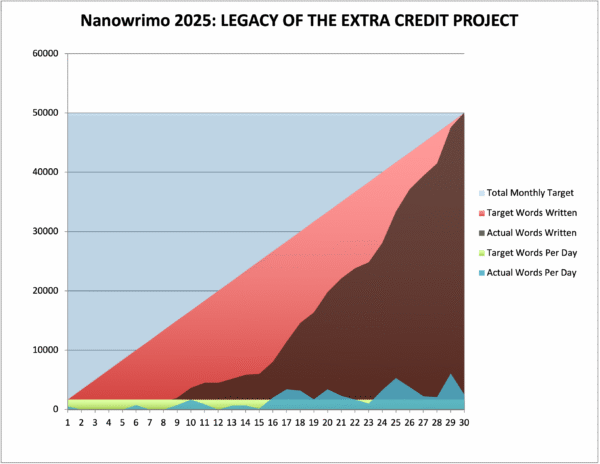

Other than a brief blip around day 8, where I was as far behind as I ever have been, this project was pretty typical of recent Nanos: a slow start as I re-acquainted myself with the world, and a strong finish as I typically ended up with more ideas than I could write down in a day. I'm going to write more tonight, in fact.

And, at last, an excerpt. I liked this bit and thought it turned out well, though it was perhaps one of the most difficult pieces of writing I ever had to write, since I was under spiritual attack (as I have been for a lot of this project, for some reason). Almost every interruption imaginable tried to stop this text from existing:

The “book” is perhaps the most amazing development since the invention of language.

The invention of “language,” itself, of course, had serious drawbacks, requiring evolution to greatly expand our gooey, calorie-hungry brains, with a consequent increase in later-life lower-back problems from all the extra weight, and a rise in complaints from women in labor that whoever this “evolution” person was, he could go fuck himself if he really wanted to push an entire human head out of that small a hole, and she’d take the epidural now, thank you.

The “speech” invention greatly improved on language by letting people actually share their ideas, but it required flapping one’s mouth so hard that the literal air figuratively knocked your ideas into someone else’s head. The concurrent “signing” invention greatly improved the accessibility of speech, both to hearing impaired individuals and to anybody who happened to be dying in the cold vacuum of space, but at the cost of angry debates among linguists, many of whom didn’t like having to study gesture and language at the same time, and had become overly attached to the idea of titling their masterworks on the origins of language something like “It All Started With the Word.” This debate was resolved, however, by Moan Skychomp’s development of the unified cognitive theory of profanity, which proposed that speech and gesture developed together when some forgotten genius stubbed their toe on a rock and simultaneously invented both “swearing” and “the bird” while cussing the very first “blue streak,” a hypothesis documented in Skychomp’s popular magnum opus, “It All Started with the F-Word.”

With the release of “writing,” language really started to jazz it up. This invention went through a rapid sequence of “point updates”, from tally sticks to cuneiform to hieroglyphs to scrolls, and soon there was an absolute explosion of people writing things down for no damn good reason. But, even written down, language was still hard to share, as tablets were heavy, scrolls were cumbersome, and pharaohs tended to send armies after you if you carted off a wall inscribed with hieroglyphics.

The “book” changed all that.

A “book” is an idea. Now, the book is strongly associated with its popular “codex” form factor consisting of thin leaves or “pages,” bound into a portable rectangular prism noted for both its random access features and its tendency to close upon itself unexpectedly just when you’ve found the page you want. But the actual book invention per se is the simple notion of gathering the ideas you want to share into a precisely-defined, self-contained, and, well, share-a-ble unit. Whether as text gathered into a codex, words spoken aloud, bits transmitted into an e-reader, or substantial form conjured into an infinite scroll, all editions of a book can be seen as sharing the same essence of “book” (except audiovisual forms, which often lose something in translation, leading to the common phrase, “the book was better than the movie”). In essence, a book lets the same piece of writing be shared as multiple copies across a vast reach of space and time.

And so, as an idea for sharing ideas, the “book” became the most successful tool for disseminating knowledge in the history of human civilization, enabling “authors” to share their ideas with “readers” not just all over the world, but even across the ages of time itself.

At least until a mad wizard decided to set every codex in existence on fire.

The structure of LEGACY OF THE EXTRA CREDIT PROJECT leaves me a lot of room to work in little sidebars like this between the actual action chapters, so I am having a great deal of fun with the story of Q'yagon Nightstrider the zebra elf, Darina Voidweaver the spidaur, and their many fun misadventures.

Of my post-Dragon Con projects, this was #3 of the ones that have urgent deadlines before the end of the year. There are 2 more, one due tomorrow, and one that was pushed back to January 15th, so hopefully starting on Tuesday I can return to blogging on a more regular basis.

Onward!

-the Centaur

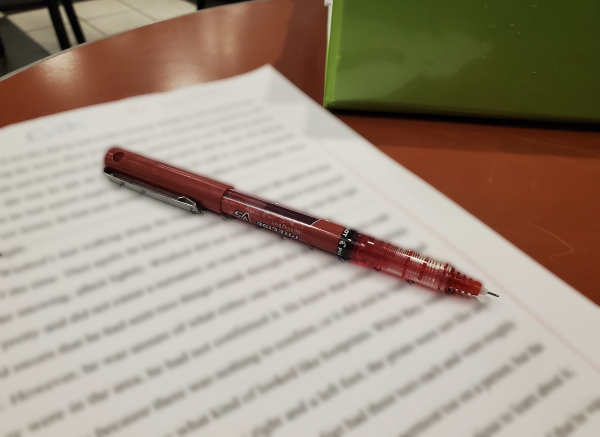

Pictured: Stats from the last 45 nanos, and from this year.