So I recently came across a tutorial for game development that seemed pretty interesting, so I decided to give it a try. The tutorial was in Rust, a new language that I’d been hearing about, and so I thought it would be a good idea to learn that too.

I even found an online playground, https://play.rust-lang.org/, which lets you try out the language in the browser, much like the Go playground: https://go.dev/play/. I quickly started trying out some simple functions that I use a lot in a variety of languages …

… and got stuck right away on Rust’s lack of function parameters.

There’s a whole blogpost https://www.thecodedmessage.com/posts/default-params/ on why this antifeature is actually, in the minds of “Rustians,” is a good thing, but even that admits that the alternatives that the language provides “might seem worse than useless.”

I’m sorry, I’ve gone through this kind of Stockholm Syndrome thinking before, where users held hostage to the good features of a language start coming up with excuses for its warts. For example, take the Go programming language. Programming Go felt like a breath of fresh air, but it was literally worse than useless for my use case - I had to write the software I wanted in C and then call it from Go. And the language itself had terrible warts from the terrible choices made by the core Go team - at the time I used it, no support for generics, endless proliferating error checks, and worst of all, an overly verbose unit test style which threw out everything we’d learned from Java and Python about how to write tests using semantically meaningful methods like assertIsNotNone or assertIsEmpty.

I’m not saying I’m not going to not learn Rust, nor that I’d never use Go again. Hey, one day I may be a convert! But, based on what I know now, I would never recommend these languages to anyone. My recommendations for programming languages remain the same "Big Three, Plus One":

- For most tasks, use Python.

- If you need speed, use C++.

- If you work with a very large enterprise, consider Java.

- If you’re working with a system that uses a specific language, use that language: C in the Linux kernel, Javascript on the web, Swift in iOS, Java in Android, PHP in WordPress, C# for Unity, and so on.

Many of the alternative languages that you can use - Go, Rust, Scala, Clojure, even my beloved Mathematica, Common Lisp, or J - are actually worse than useless for most tasks, for two reasons.

- First, most of them are less baked than the Big Three, and are less ready for developing real applications; they’re not chosen for their fitness to purpose, but instead chosen by zealots who are trying to make a point. Don’t be a zealot trying to make a point.

- Second, working on these other languages actually detracts from making the Big Three better. The C++ of today is almost unrecognizably usable compared to when I first started using it, and Python and Java are rapidly adding new usability features as well.

That doesn’t mean we don’t try new things. C++ has mostly replaced C, and TypeScript is edging out JavaScript; who knows, perhaps, one day some variant of Go or Rust or Swift will become the dominant paradigm. (But, honestly, I hope not).

Nevertheless, I remember talking to a programmer friend about a refactoring I wanted to accomplish, and he angrily sketched out a better build system which could have solved the problem using a Turing-complete constraint language to figure out the dependencies.

I just remembered the famous quote from the creator of ANTLR - “Why program by hand in 5 days what you can spend 25 years of your life automating?” - and handwrote a script to solve the problem in an hour, and got on with my life.

-the Centaur

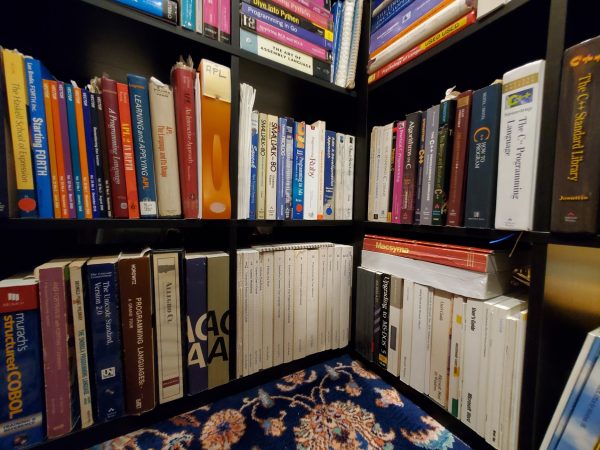

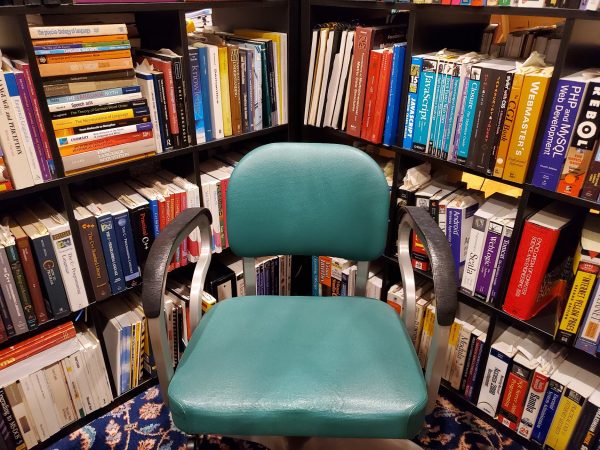

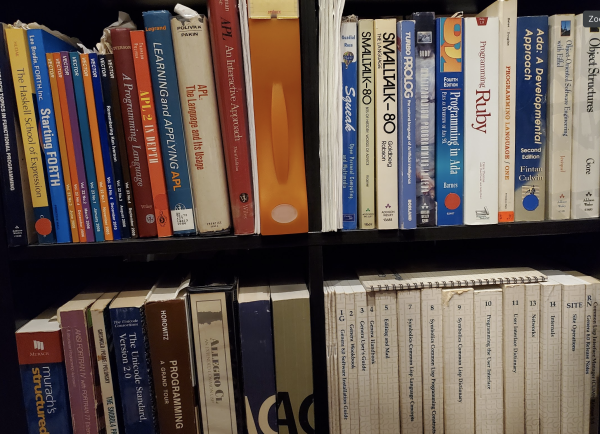

Pictured: Some of the older programming language books that I have in my stacks, most of which are now worse than useless for getting things done nowadays - though if you really love programming languages and learning how things work, they're more than priceless, now and forever.