Pride. One of the "Seven Deadly Sins." Overweening confidence in one's accomplishments. Sooner or later, if you study Christian thought, you'll come across the idea that pride is one of the worst sins that you can fall into. I'd put self-righteousness over that, but, hey, the two go together.

Another common idea in Christian thought is the difference between Christian values - "the Kingdom" - and values in our society - "the World". We encounter this every year when Christians engage in performative lying about "the War on Christmas" every time someone says "Happy Holidays."

But the difference in the Kingdom and the World is important, even though hyped-up Christians imagine differences which are not there - for example, some say "Happy Holidays" just to change it up, or say "Holiday Party" because (a) the office party isn't on Christmas and (b) people of other faiths attend.

The difference is important because our society, while it might be a vast, distributed artificial intelligence of sorts, itself isn't a rational agent which follows God's will. That's up to us, as individual humans, and as we've talked about earlier in this series, us finite beings are always prone to messing it up.

So we're constantly called to rise above what our society does by default - to turn away from the values of the World, which develop through their own inertia - and to consciously choose to follow Jesus, exhibiting the kind of values He would exhibit if He were here among us.

On that note, one might imagine that Jesus wouldn't have been too wound up over whether the office end-of-year celebration was called a Christmas Party or a Holiday Party, but He might take offense at stripping Christ out of a personal Christmas Party, or - "You're celebrating my birthday in December?"

Another difference between the Kingdom and the World is the focus on self-actualization and pride in one's accomplishments. A lot of Christianity depends on overcoming our own worst impulses, which seems precisely opposite to our modern culture's increasing focus on self-acceptance.

These are not as incompatible as they seem. The world has engaged in spectacular, mind-numbing repression on a vast scale - most noticeable in totalitarian cultures, where even the language gets edited to reflect political authority - but down to the massive but almost invisible conformity forced upon us.

One of the arguments in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman is "You don't raise a guy to a responsible job who whistles in the elevator!", with one character getting fired over it. I and my father, a generation and a half apart, argued over this, and he said he'd reprimand a man who did that.

My father was a great man, and he built a great business, but I'm working in a great business too, and it's filled with responsible people doing excellent jobs who've named themselves after flowers, and once I saw a very serious presentation by a very serious person wearing a Pokemon onesie.

I could go on a riff here about how we've moved past the strict IBM business culture of the 1950's and discovered that most of those surface features don't matter for doing excellent work - they were holdovers from the Victorian era, perpetuated by anal-retentive power freaks. And I'd be right.

But something has entered here, subtly, trying not to get noticed: pride. Because being right about the job part misses the real point to be made: Whether someone should get reprimanded or not, whistling in an elevator makes a lot of noise in an enclosed space. It's arguably rude and shows little self-control.

But it's hard to be open to that point if you're only seeing your own side of the argument, which may be correct, but not complete. Recently, in a virtual meeting where I'm sure at least one person was wearing a funny hat, we had an argument over whether we should support one or two pieces of software.

A very senior executive argued we should push for one; I argued to keep two (or more broadly, as many as were needed). But the executive didn't stomp on my point; in the chat for the meeting, they pointed out they agreed for that particular topic, and outlined circumstances why we might choose either path.

They even used math to justify the argument - one of my arguments, simplex math, the notion that software complexity is the square of the size of the product, so if you can support two simple things, that can sometimes be cheaper than supporting one over-complex thing that tries to do it all.

We both learned something in that meeting, because we were both open to hear it. But if either of us had been caught up in the pride of our points, that understanding would not have been possible. And the executive would have won by default, since he'd accomplished way more than me.

Some Christians take it that all pride is bad. Sometimes it even gets capitalized, like Pride, and gets a corner office. That's useful: I distinguish between the English word "pride" - being rightfully happy we accomplished something - from Pride, in the sense of excess egotism about ourselves.

C. S. Lewis once said that if a Christian was the best in the world at something, he should honestly and sincerely acknowledge it - and then forget about it, as he moves on to the work to be done for the day. And that part of the Christian journey is constantly tamping down these self-aggrandizing impulses.

I think Pride does more than lead us down the wrong path. It leads us into a state of self-absorption, where we are so convinced of our own accomplishments - and maybe we have some - and of our own rightness - and maybe we are - that we can't see the accomplishments or rightness of others.

Christians say God is infinitely good. Constructivist mathematicians say there's really no such thing as "infinite", only series which expand without limit. There's no infinite number, just a number one larger than any number choose. In the same way, no matter how good we are, there's always a way to improve.

Pride isn't just placing our will over God's. Pride internalizes our accomplishments and so aggrandizes our selves. Furthermore, it's a particularly hard sin to overcome as that self-aggrandizement serves as a blinder to information that might contradict that inflated self-assessment.

Pride isn't just a sin. It's a distraction from turning towards the right path.

Fortunately, Jesus is always there for us to follow.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Dustin Hoffman as Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

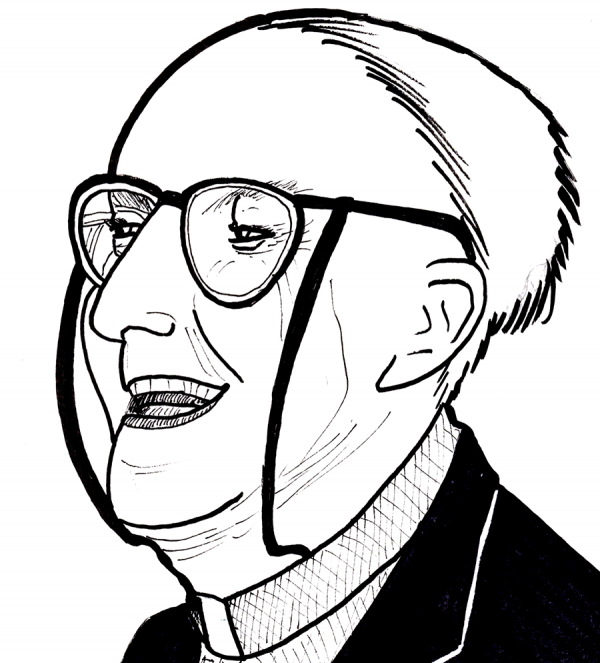

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.