You know, Lisp was by no means a perfect language, but there are times where I miss the simplicity and power of the S-expression format (Lots of Irritating Silly Parentheses) which made everything easy to construct and parse (as long as you didn't have to do anything funny with special characters).

Each language has its own foibles - I'm working heavily in C++ again and, hey, buddy, does it have foibles - but I always thought Lisp got a bad rap just for its format.

-the Centaur

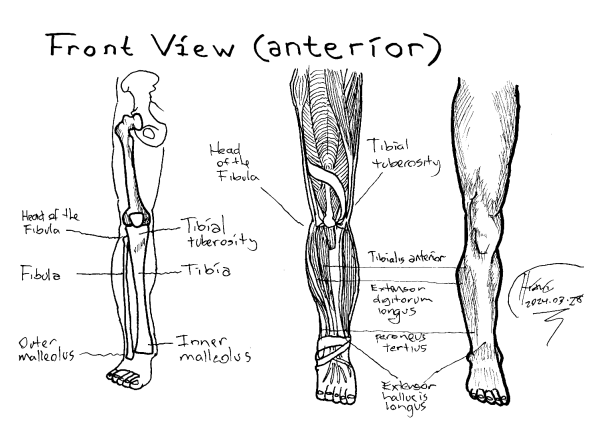

Pictured: a Lisp function definition (with the -p suffix to indicate it is a predicate) with the side effect of printing some nostalgia, and executing that statement at the Steel Bank Common Lisp command line.