Christianity has all sorts of weird words: Primum Mobile, Eucharist, Paraclete; there are other words which are used in weird ways, like adoration, adoption … and apologetics. “Christian apologists” doesn’t refer to people who are apologizing for Christianity: it refers to theologians trying to defend it.

As I hinted at last time, in a worldview where belief in God rests on faith as a free gift of grace from God, Christian apologetics are both indispensable and unnecessary, essential and impossible. Christians are called on to spread the Gospel, with the knowledge that no rational argument can ever convince.

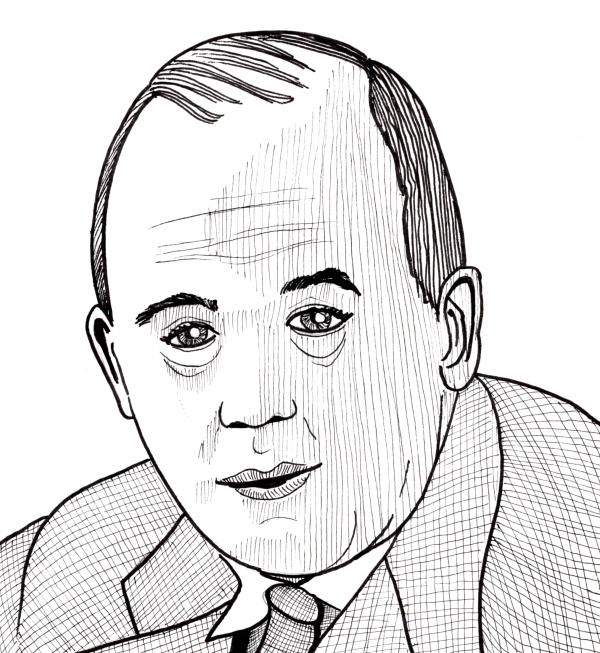

That hasn’t stopped people from trying, though. The greatest Christian apologist of the past two hundred years, full stop, is C. S. Lewis, author of not just the Narnia series but also great apologetic works like The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce and The Abolition of Man.

And so, while Lewis’s works have moved me greatly, I often find his works have holes in their hearts. The brilliant G. K. Chesterton, author of In Defense of Sanity, is even worse; his favorite trick is to turn common ideas into paradoxes to make a point – frequently at the cost of intellectual honesty.

I’ve heard it said that Chesterton argued that all great things contain paradoxes, because at the heart of everything is the paradox of the cross: a tool of condemnation turned into salvation, death turned into life, failure, humiliation and defeat turned into success, glory and victory.

And this is perfectly good Christian theology – and consistent with Godel’s incompleteness theorem that we discussed earlier. Most Christian religions assert that at the heart of the faith are mysteries that cannot be fully understood, just like Godel showed that all systems of thought have ultimate limits.

But it’s unsatisfying for a rationalist, even a Christian one, for it means that many Christians – even as they are sincerely trying to do their best to spread the Gospel the best way that they know how – are at the same time committing to statements that are at best foolish and at worst lies.

And if you are tempted to retort that it’s good to be foolish in the name of the Lord, like David with his tamborine, I want to be super crystal clear that I don’t mean the good, faithful kind of foolishness, but a performative, “bad faith” foolishness in which people pretend things are other than what they are.

You’ve met the type. The street preacher with the specious comeback; the televangelist who carefully edits his stories to play his position. The new “friend” who, when they find out you are a Christian, asks “Why don’t you come to my church?” with the words “instead of yours” hanging in the air.

For a Catholic growing up in the south, in Greenville, South Carolina, hometown of Bob Jones University, this was particularly irksome. As a child, I was buttonholed by street preachers across the street from BJU, who’d pester me on subsequent weeks on whether I’d read the pamphlets they shoved on me.

If these people find out you believe in evolution, whoo boy, the volume gets turned up to eleven. I aaalmost ended up going into evolutionary biology as my field, and I can’t tell you how many bad arguments I’ve heard about why evolution won’t work. No, not bad arguments – meaningless.

But it wasn’t just evolution. Many of the arguments which were forced upon me were purely theological. One argument really stuck with me – a true Chesterton style paradox, what at first appears to be a nearly meaningless argument which nevertheless captures an important truth about Christianity.

Call this “argument” the Cross over the Chasm. The idea is that in the beginning, God and Man were united, but Adam’s sin caused the Fall, creating a chasm that cannot be bridged. Man can try to cross the chasm with good works, but fails; God can try to cross it with grace, but grace doesn’t reach either.

But that’s where the Cross comes in. While the arm of good works can’t reach, and the arm of grace can’t reach; but you can write Jesus vertically between them, and turn those two arms and the word Jesus into a cross that bridges the gap. Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross bridges the gap between god and Man.

Now, what’s bad about this Cross over the Chasm episode?

By itself, nothing, but in the moment, what happened was this: a friend found out that I was Catholic, and decided to “show” me the true role of Jesus in religion – except of course, in the mind of people like him, he doesn’t have a religion, but a close personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

Never mind that this “argument” doesn’t actually “show” anything – at best, it’s a mnemonic for a few bits of theology which are perfectly consistent with Catholic doctrine. (Many people in the Bible belt who are upset about what Catholics supposedly believe don’t realize there are fewer differences than they think).

But the real problem is that people who act like my friend did there are both implicitly rejecting the faith of fellow Christians – and lying about their own faith. Religion is the word we use for someone whose close personal relationship with an invisible person is a vital part of their worldview. Denying that is a lie.

And denying the faith of a fellow Christian is attacking that faith. I also have a personal relationship with Jesus Christ – which, in humility, I’d never describe as close, because it’s never as I’d like, a relationship I’m always trying to improve, with the help of His grace; but I do believe and I choose to follow Him.

That’s super hard, and we don’t need to throw stumbling blocks up for other believers. For a Christian, other Christians should not be our theological enemies. And so, while I don’t believe in buttonholing Christians to get them to convert to other branches of Christianity, I think it’s good to ask:

What was good about the Cross over the Chasm episode?

Well, first off, it’s a really clear mnemonic for really important theology. It’s a great little story which clearly shares important truths about Christianity: humanity and God are separated, but reaching for each other in works and Grace, and Jesus – and His sacrifice – is the mediator that makes union possible.

It’s not at all a logical argument, but the story has stuck with me for years. Had my friend come up to me, enthused, about this new metaphor, rather than presenting it as one more argument against my faith (!) even though it didn’t contradict my faith (!!) it could have acted as a bulwark, not a stumbling block.

More importantly, at least my friend was trying to share the Gospel. Once a woman told a televangelist she didn’t like how he was spreading the Gospel. He asked how she was spreading it. She replied that she wasn’t spreading it. His response: “Well, I like how I’m doing it better than how you’re not doing it.”

I’m acutely aware that many people don’t want to be proselytized, and that’s their prerogative, of course – I know from experience I don’t enjoy it myself. I far prefer the Episcopal “Tea with the vicar OR DEATH!” “Oh? Well, tea please” to any amount of street preaching or personal buttonholing.

But, if you are interested in the Christian faith, know that ultimately, rational argument will fail.

A paradox – a mystery – lies at the center of the faith: “Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.” While I’m comfortable with this idea, sometimes it takes a Chesterton paradox – or a sketched diagram of a cross – to break through the rational so that the free gift of grace will start working.

-the Centaur

Pictured: C. S. Lewis.