Coveting is distinctive among the Ten Commandments in that it is a thought crime. For those not familiar with the Ten Commandments, they’re a set of guidelines from God in Exodus and Deuteronomy in the Bible. How the guidelines break into “ten” is up for debate, but the rough outline, loosely interpreted, is:

- God is the Lord of everything.

- Don’t have any other Gods.

- Don’t misuse God’s name.

- Keep the Sabbath holy.

- Honor your parents.

- Don’t murder people.

- Don’t commit adultery.

- Don’t steal things.

- Don’t lie in court.

- Don’t covet your neighbor’s stuff.

The first command is a statement of God’s authority; the second through the ninth are involve some kind of action – making an idol, cursing a blue streak, shopping on Sunday, dressing up like a bat, killing Bruce Wayne’s parents, making off with the Lost Ark, telling Tom Cruise he can’t handle the truth.

But coveting is different. You don’t have to physically do anything, like take your neighbor’s nice new car: you just need to think about it. Jesus goes even further in Matthew 5:27-28, suggesting that if you look at a woman with lust, you’ve committed adultery with her in your heart.

Seems harsh, but I’ve heard priests speculate that God’s reasoning behind these challenging passages is that coveting is really bad for you. It’s not just that coveting your neighbor’s house, spouse or possessions is a gateway to theft or adultery, it’s that it puts your brain in a bad state.

Coveting is “yearning to possess something”: possessions themselves are things which can possess us if we are not careful. But there’s nothing wrong with wanting something per se: you can want a soda if you’re thirsty, a better car if you’re in the rat race, the four walls of your freedom if you’re a monk.

But coveting someone else’s possessions – not wanting a house to keep up with the Joneses, but wanting your neighbor Jones’s specific house – is the problem. Coveting the possessions of others puts us in mental conflict with the people around us, which can lead to real conflict.

So even though it seems innocuous, coveting is a pitfall which is important enough that God wanted to warn us about it. But in a way, that makes coveting a very obvious pitfall. Unfortunately, coveting is just one of the ways that our human brains can go wrong with regards to our view of the people around us.

One of the modern “technologies” that humans have developed for maintaining the health of our minds is cognitive behavior therapy, a collection of experimentally tested cognitive and behavioral psychology techniques, designed to improve our well-being by detecting and correcting bad thought patterns.

These “cognitive distortions” can be self-destructive – thoughts like “I’m not good enough” – but they can just as easily be self-serving – “Everything would work out if they’d just listen to me.” These self-serving narratives have the advantage of making us feel good about ourselves – but they don’t better ourselves.

When we interact with other people, a healthy mental response keeps things in perspective. Someone speaks over you in a meeting, which happened to me a lot today; but you recognize that there are simple explanations involving no bad intent (as it turns out, my internet was flaky, and my voice kept cutting out).

But when cognitive distortions kick in, simple events like that can get overgeneralized (“This always happens to me”), magnified (“They didn’t hear me at all”), can swamp out positives (like forgetting the good stuff) and can lead to catastrophizing (“Everything is going to hell in a handbasket”).

These distortions aren’t accurate, but they enhance the intensity of the events, worsening our stress levels – but, paradoxically, making it feel a relief when the events are over, giving us a bit of a dopamine hit for surviving the encounter, leading to the distortions growing stronger and stronger.

Cognitive distortions can turn into internal narratives, which can turn a momentary event into a years-long obsession. On one volunteer project, our group leader took offense when the previous leader tried to boss me around. I’d barely remember this, if our group leader didn’t bring it up every time we talk.

Loving your neighbor as yourself is hard. But Jesus also says in Matthew 5:44 that you should love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you. Jesus clearly meant this to be directed at real enemies, people who’ve harmed us, but it applies with equal force to people who we just think have harmed us.

Loving your enemies is really hard if those enemies exist only in your own mind, because your cognitive distortions will twist anything that they do into something that is evil – like in politics, where partisans disbelieve anything the opposition leader says, even if he’s reading the time off of an atomic clock.

But learning not to covet is like … training wheels for eliminating cognitive distortions. It’s good and healthy to want a sandwich if you’re hungry. It’s not so healthy to want someone else’s sandwich. Perhaps that won’t motivate you to take it. But you might think they got the better deal.

Even in something as petty as who gets the best slice of the cake, we can build tiny slights up into a tower of resentments. Techniques such as “one cuts, the other chooses” may be game-theory optimal, but we are rarely in situations where these techniques can always be applied.

So the solution starts with us. Don’t covet your sister’s slice of the cake. Don’t resent your coworker’s “DAYYMNN” sportscar. (No, really, it is VERY jawdroppingly nice). Don’t covet your neighbor’s spouse. Learn to distinguish between wanting to improve your situation, and envying the situations of others.

Building the cognitive tools we need to avoid self-serving narratives is hard, because each person’s mind and situation are unique. Fortunately, we can start with something easier, something both easy to detect and easy to fix, by following the tenth of the Ten Commandments: do not covet your neighbor’s stuff.

-the Centaur

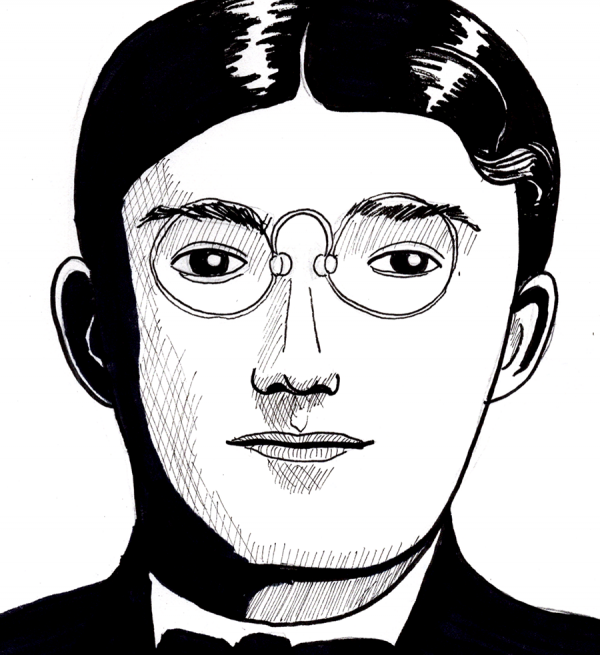

Pictured: John Watson, founder of behaviorism.