I don’t know that Nero was eaten by coyotes. I only know that our big black fuzzy cat went out around the hour of the wolf Thursday morning, August 21, and never returned.

What happened to Nero is unknown, and thus open to infinite possibilities. Everything we know about his departure can be expressed in “didn’ts”: We didn’t see him leave. We didn’t see him return. He didn’t come in through the cat door. He didn’t come for the food I left for him Thursday morning. When I left for work he didn’t prowl out of the little outdoor den he’d fashioned under the bushes. When Sandi got up he didn’t come in. He didn’t turn up when she went looking in the neighbord. She didn’t see his broken body hit by a car. He didn’t return that afternoon, that evening, or the next. He didn’t have a collar, having thrown three in two months. He didn’t have a microchip. We didn’t find him in further walks through the neighborhood. We didn’t find his chewed up remains in a walk through the hills. We didn’t find him in the county’s online listings of found pets. I didn’t see him in any of the cages when I toured the shelter. I didn’t see a match in any of the dead-on-arrival listings at the pound.

Of all the reasons that Nero might have disappeared, why coyotes? Why not assume he got hit by a car (where was the body?) or taken in by a nearby family (at 3 in the morning?) or simply ran off (without his food bowl, suitcase or favorite collection of toys?). If he could have simply fallen off a fence and died, or gotten into a fight with another cat and was holed up nursing his wounds, or could have been killed by a dog, or have had a heart attack or seizure?

Well, I could say that coyotes are one of the few species whose habitation has expanded with the growth of human population, because humans have killed the larger predators that keep them in check, because they get along better with humans than wolves, oh, and because idiots feed them, emboldening them to move into human territory where they can feed off garbage and stray pets. Attacks on dogs are more often reported because cats rarely survive; coyotes have been reported to feed off feral cat colonies and, later, on the food that humans were putting out for feral cats. Coyotes have known to scale walls to attack pets, to use advanced techological devices for more difficult kills (that’s a joke), and even to steal purses from unwary women (surprisingly, that’s NOT a joke) .

But the real reason I suspect Wile E. is that in the past three weeks we’ve been hearing coyotes in the hills behind our house, right around the same time frame that Nero goes out in the middle of the night. Sometimes it is just one; other times it’s a howling cacophony. Our home is only one street away from the hills, and jackrabbits have been bold enough to enter our yard and try to eat the dry cracked twigs we pass off as our grass, so a predator might follow prey down into our area (or Nero might have followed a rabbit back into danger). And recently as a week ago, Nero came in, worried and shaken, not wearing his collar, as if he’d been through some great trauma, like a catfight or a coyote attack. He wasn’t scared of going outside, though, so we didn’t make the connection; I just assumed he’d gotten his collar caught on something, and had had to fight to take it off. But he disappeared in the night, right around the time the coyotes how.

The other explanations don’t seem to hold water. Of course, if he’d been hit by a car and someone threw him in a Dumpster, or if he’d been eaten by a dog, there would be no trace; but Nero’s actually somewhat suspicious of both cars and dogs so I’m not so worried about that. We have some suspicion that a neighborhood girl who was sweet on Nero finally coaxed him to go home with her: she once tried to argue that Nero was a stray even though my wife was standing there telling her the cat was ours; however, it stretches my imagination to think she would have taken Nero in the middle of the night. Sometimes cats who are injured go off to a quiet place to heal or die; but the last time that cats in this area started vanishing, it was eventually traced to a fox that was preying on them. Perhaps the fox is back. Perhaps the fox has been eaten by the coyotes, which at up to 45 pounds weigh in at three times as much as Nero’s fighting weight, and which, for smaller prey, adopt a catlike stalking behavior, pouncing on their victims and subduing them rapidly with long, sharp, teeth.

Odds are actually good that Nero will return. Published studies indicate over half of cat owners that lose their cats see them return: that number isn’t as good as dog owners, over two thirds of which are reunited with Rover. Information by our local animal shelter indicate, however, that over 90% of pet owners that get to the point of reporting their pet loss never see their pet again, unless they were microchipped and/or collared (see the note about thrown collars earlier). That doesn’t jibe with the published stats, probably because the pet owners who see their cats return immediately don’t get around to going to the shelter. Certainly in Sandi’s experience she’s had cats disappear from anywhere from two to eleven days, and her mother has similar experiences. So we haven’t given up hope yet; I personally plan on waiting a month. But I had this nasty, sinking premonition the morning he didn’t show up for his food, which has happened before; and this makes me wonder if there was some noise during the night when he was taken, some awful caterwauling that penetrated only my subconscious as I slept, leaving me waking up with no sure rational knowledge but a deep emotional foreboding quickly crystalized into an irrational certainty that’s hard to shake.

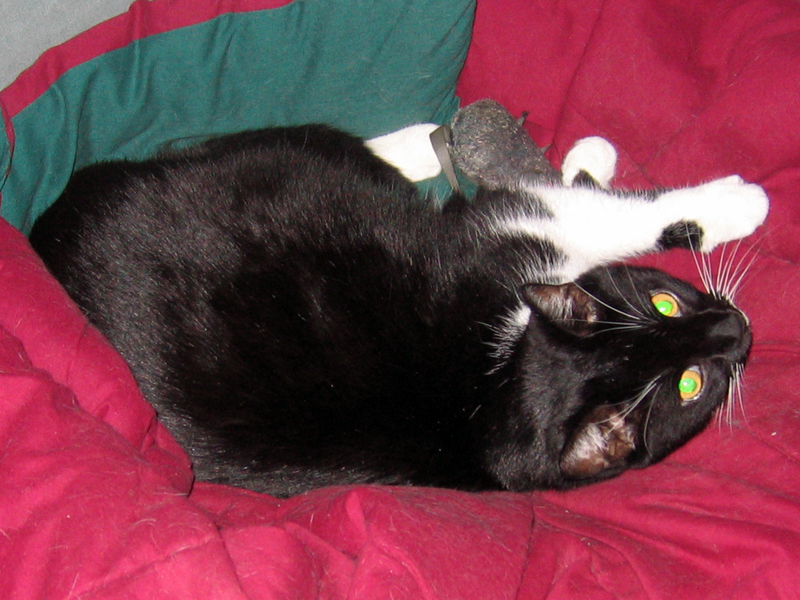

What hurts about this most was is Nero’s surly, irritable nature. Unlike the dogs that I’ve owned, or Nero’s brother Caesar, Nero was neither giving of love nor unconditional: he was moody, wanted his alone time, and was most likely to want to be with you when he was working to get fed. But that surliness made the affection he showed stand out even more. He’d come pester you when you were sitting on the toilet, or demand to be petted when you were brushing your teeth. He’d hop up into your car as you were packing to go to work, or hop in and take a ride when you came home. When he saw you Nero woul

d meyow surlily at you, kicking his head back in an inhuman but completely recognizable gesture of greeting; then in the middle of the night he’d come and sit on your chest and nuzzle you as you scratched behind his ears or on his nose. He was a surly, burly cat, so you could really tell when he liked you.

No, I lie. He didn’t do all these things just any abstract you. He did these things primarily to me me. He was nice to Sandi, and could be warm to other people, but we bonded with each other rapidly and completely. Even his annoyances were endearing – lifting up to as if to open a doorknob, shoving his way into the broken bathroom door and letting the cold in while you showered, hitting you with an oddly concerned “mrowr” (sounds like “meringue”) that for all in the world seemed like he was saying, “you damn fools, what are you doing in all that water? Can’t you see it’s made all your fur come off?”

Sandi and I traded off imagined dialogues with the cats, her speaking to them and me filling in the responses: “Poor little monkey!”/”I’m not a monkey.” and “He’s a good dog!”/”I’m not a dog.” Sandi developed her own doggerel songs – “he’s Nero, he’s Nero, he’s big he’s heavy he’s large.” – and I did the same – “Neurotic. Neronic!”, “Nero, Nero, you’re my hero!”, and so on. Some of those lines seem creepy now. The last thing I did for him was pick him up and give him a big hug, saying, “I’ll hug him and squeeze him until there’s not a breath left in his body.” And when I left and didn’t see him, I cried after him, as I often did, “He’s Nero, he’s Nero, the tasty and lovable treat.” / “What?!” It started a month back as a joke. It doesn’t sound so fucking funny now. I’d gotten to the point that I’d sing “fuzzy, fuzzy, fuzzy cat” when I’d hop on 85 south when leaving Google. Now I still do the same thing as I leave, then catch myself and grow angry enough to punch a wall. Good thing I’m usually driving when it happens, but still.

Once when I heard the coyotes out a few nights after Nero was lost, I picked up my baseball bat and strolled through the neighborhood, walking with it like a cane as cars passed, swinging it grimly while alone. The outdoorsmen among you, who know what even a moderately sized wild animal can do to even an adult human, might think that this was foolish bravado on my part, but what you probably don’t know is that I know the dangers better than most, think about them more frequently than most, and went out that night prompted by anger but acting on a deliberate, premeditated strategy of my own that I adopted long before I came to befriend Nero. Whether I came back or not, anything smaller than a Bengal Tiger that I met on the path would have run in fear of humans for the rest of its life.

Which might make you think I have a death wish, or a hatred of coyotes. I don’t, on either count. I’m glad I chose to live in the green hills of Santa Teresa, a place where the biosphere is still functioning and alive, unlike the dead land and canned parks of the cities surrounding the Bay itself. I regret that the active life around us apparently claimed Nero’s life, and would act to repel the coyotes from our homes; but not from our hills. Animals should fear humans, but as long as they do, they can coexist with us. I regret that letting Nero out apparently claimed his life, and will act to microchip Caesar and make sure he wears his collar, but will still let him out. Pets should be protected, but as long as it is reasonably safe, they should have some freedom.

Life is risk; and I’m glad Nero got to spend his last few months in a place where he was treated well and got to experience the outside. His story was a sad one: his original owners reportedly got on drugs and planned to release Nero and Caesar to the wild when they lost their home, which sounds good except for the bit that they were taken from their parents too early, are completely domesticated, and for all practical purposes can’t hunt. One of our bridesmaids took them in, and after many months bouncing between closets and spare bedrooms of foster owners, all of which had too many cats already, we took them in and had them shipped out to us. They were traumatized by the flight, but Sandi had a plan to acclimate them which worked beautifully, and other than a little conditioning on my part to reduce the areas in which they might fear me (picking him up outside but not taking him in; putting him in the car but not taking him to the vet, etc), they needed very little training.

Nero in this sense was unearned, a gift from God: unlike the vast investment of a child or the lesser investment of a kitten, I got him full-formed, the living embodiment of my prayers for a cat. My image of the ideal cat was derived from a friend’s cat in college, a black cat with a white blaze. Over time that image evolved in my notebooks to Cleopatra, a robotic black cat in many respects to Nero except for gender, appetite and processing power. When Nero arrived I was so caught up in making the fragile, frightened, surly beast warm up to life that I didn’t even notice the similarities to my fictional robotic pet; by the time I did notice, Nero had eclipsed Cleopatra and had captured my imagination all his own.

What a cat. I loved his glossy black fur, his rich white throat, his fuzzy, gentle paws. His right eye went cloudy in a scrap with some unknown opponent, and he’d frequently be covered with little nicks and scratches from battle that he’d let me scratch at until a tiny little tuft of fur would come off. He loved rolling in the dirt, and was slow about cleaning himself – until you got on the computer, at which point he’d show his love of your lap, then the spacebar key, then hop up on the glass surface of the table and plop down so you couldn’t see the lowest lines of whatever you were writing on the monitor.

Nero’s dead and he’s never coming back. When does an irrational certainty become real? Never. If he died how I think he died, I’ll never know, and I have no feasible actions that can cast light on this. Only a suspicious fear, an irrational certainty, that only time can prove to be either a sound judgement (if he stays gone) or a borrowed bit of trouble (if he returns). I imagine that he’ll come back, bruised as if from a fight, that we’ll rush him to the vet and find that he’s fine; Sandi imagines he’ll come home, chipper, as if nothing has transpired. “What? What are you crying about? And where’s my can food?” Anything is possible; Sandi’s had a cat gone eleven days. My uncle had a dog gone for over a month. Nero’s gone, but he could be back any minute. Really. He could.

In the mornings I still drive off, thinking I’ll see him come out of his little outdoor den, or see him run over to hide by the olive tree in the front yard. In the even ings I still drive home expecting to see him sitting in the driveway. At night Caesar still looks off in the distance, expecting him to come in the door when he goes out (to maintain cat parity) or to join him for a nice bit of C-A-N food. At bedtime I still open the door and call his name late at night, expecting him to come home. In the middle of the night I think I’ll still wake up and hear him hop on the bed, feel him crawl up on top of me, feel him stretch out a paw to touch my cheek, and hear him, under the scritching of my fingers under his chin, give off his soft, endearing, almost cooing purr.

Nero was a surly, burly cat, so I could really tell that he liked me. Or, as Sandi frequently said, watching our interactions, “He loves you.” After all the traveling I’d done in July I’d been thinking I should spend more time with the cats. In August, I’d started to do it, and the last thing I did for Nero was pick him up and give him a big old hug. If I had a choice on what note our friendship could go out on, that would be it.

In the ten months I had him, Nero fast became the favorite pet I ever owned. I’ll miss him. And I pray to God that he proves me wrong and returns safely home.

Nero: born 2000, missing in action 2007.

If you’re reading this, Nero, please call Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh or someone else in the animal language research community immediately.

Then come home.

-the Centaur