... but do allow yourself to be influenced by their teaching.

The Bible is filled with authoritarian language. The so-called "divine right of kings," which authoritarian thugs used for over a thousand years to justify their aggression, may have gotten its start in the book of 1 Samuel, in which the people of Israel ask for a king, despite the prophet Samuel's warnings:

“This is what the king who will reign over you will claim as his rights ... He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses ... he will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers... he will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves."

I left out a lot there, but it draws a pretty complete picture of a pretty ugly king. But Samuel promises no salvation for the people who have asked for this ruler: "When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.”

Similarly, Jesus doesn't offer relief from the Roman persecutors when asked by the Pharisees if it is legal to pay taxes to the emperor - Jesus pointed out that the coin to pay the tax had Caesar's image on it: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Kings used to let this get to their glitter-crowned heads. King James (yes, that King James) once said: "The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth, for kings are not only God's lieutenants upon earth and sit upon God's throne, but even by God himself, they are called gods."

Whoa, James! That's basically calling yourself a god. Remember the Ten Commandments, specifically #1 "Thou shalt have no other gods before me." Pretty blasphemous for the guy who commissioned a translation of the Bible ... wait, the King James Bible ... and you even put your name on it?

Well now, it seems clearer why a king grabbing at power - for James was originally just king of Scotland, which did not recognize absolute monarchs - would commission a religious text in their new country's language justifying that rule, along with manuals for interpreting it which gave him absolute power.

Those manuals, the awesomely titled Baskilon Doron (meaning "royal gift") and The True Law of Free Monarchies both laid out the divine right of kings as an extension of the apostolic succession - relying on arguments from a Bible which James worked to make available to his whole kingdom.

Now, James was wrong about the divine right of kings being an absolute grant of authority ... but he wasn't wrong to see a role for authorities in our life. Let's go back to what Jesus said about Caesar:

“Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Contra James's self-serving arguments, this isn't a call for kings to receive absolute obedience: right there on the tin, Jesus distinguishes between the respect leaders should receive and the worship God should receive. We can get a little more insight into this by looking at the context of the question.

In Jesus's time, Israel was occupied by the Romans, and the Jewish leaders were trying to trap Jesus between two bad choices: on the one hand, he could deny the poll tax, and be condemned as a traitor to Rome, and on the other, he could approve the poll tax, and be condemned as a traitor to Israel.

But you can't put Jesus in a box, hence his wonderful answer which not only splits the difference in a creative third alternative, but also provides new ways about thinking about the problem. But hidden in this answer is the rejection of the demands of the Zealot to throw off the poll tax and to overthrow Rome.

The Roman occupation of Israel was wrong, full stop. They conquered it, they taxed it, they drove it to the edge of rebellion through oppression, and after the rebellion boiled over thirty years after Jesus's death, they put down the rebellion by siege, slaughter and the destruction of the Second Temple.

But, as sad as all that was, to God, the Roman oppressors were people too. A Zealot rebellion led by Jesus would have been successful - some theologians think Jesus was the "commander of the armies of the Lord" from Joshua 5:14 - but would have led to the deaths of countless people on both sides.

Orchestrating wholesale slaughter is not what Jesus came to do. Treating every single human being with respect means that sometimes we must put aside the desire to fight injustice if that fight means bringing harm to people that can be avoided. Whenever possible, Jesus argues we should turn the other cheek.

Jesus goes beyond that. He criticizes the Jewish religious leaders throughout the Gospels, but He also acknowledges their authority: "The scribes and the Pharisees administer the authority of Moses, so do whatever they tell you and follow it, but stop doing what they do, because they don't do what they say."

Jesus is both saying we should follow legitimate authority AND saying blind exercise of authority is wrong. In Hebrews, Paul argues church leaders are on the hook for their flocks "Obey your leaders and submit to them, for they are keeping watch over your souls, as those who will have to give an account."

Jesus asks leaders to follow him to model servant leadership, saying that Gentile "high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all."

Rather than the divine right of kings, Jesus preaches that leaders should act as servants, looking out for the welfare of their flocks (and Paul argues, even their souls). These leaders may sin, but they have the responsibility to pass the law on to us, so we need to be open to their guidance.

Jesus asks us to follow Him, but He doesn't ask us to blindly follow authority: He asks us to reserve for God what belongs to God, which may mean parting ways with leaders who don't put God first. But He does ask us to follow leaders who are sincerely trying to pass on what God has given them.

It's a delicate dance. It's all too easy for rulers to fall in the trap of demanding absolute obedience, as many Catholic leaders believe about the authority of the Pope, and as many Protestant leaders believe about their own doctrines, even as they claim to be rejecting the authority of Catholic Dogma.

These are self-serving lies. Following Jesus does not mean regurgitating a catechism or swallowing a doctrine: it's a living act of belief in a real person who actually lived and actually came back from the dead, and a living choice to follow in His footsteps as we guide our lives.

The rulings of our church leaders are designed to help us; when done properly, it's done with care for our souls. Since we, too, are self-serving, it's really tricky to know whether your leadership has gotten off the path, or whether you've gotten yourself so lost that it just seems that they are.

Regardless, there's one thing we can always do to get back on track: repent and turn to follow Jesus.

-the Centaur

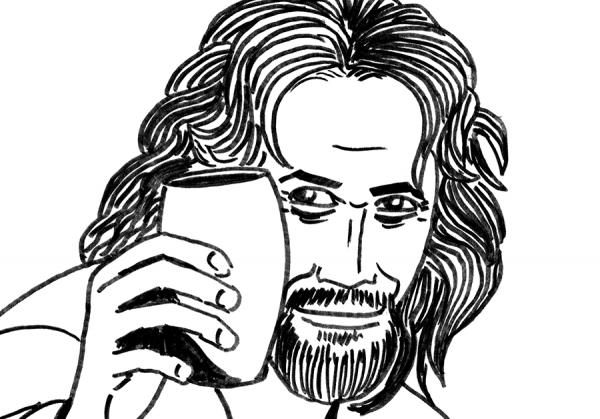

Pictured: Tiberius, who was likely on that coin.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

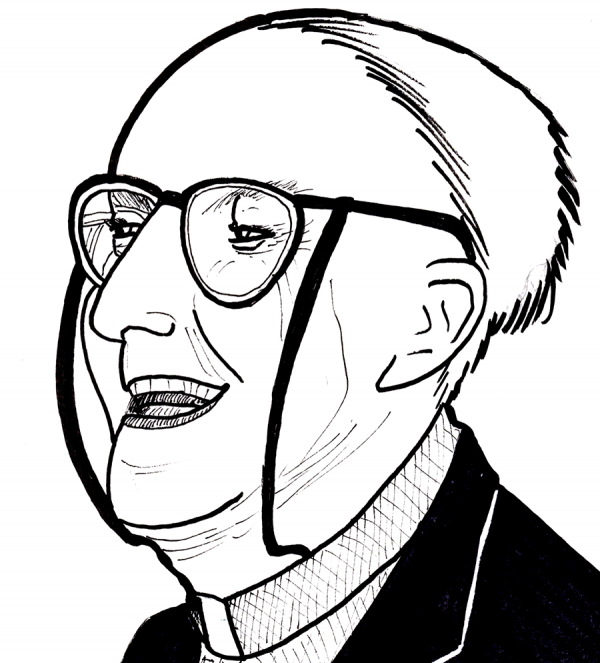

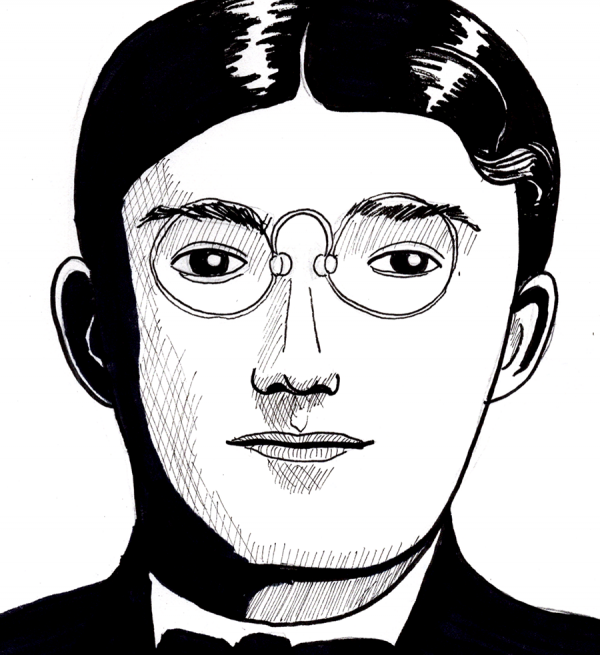

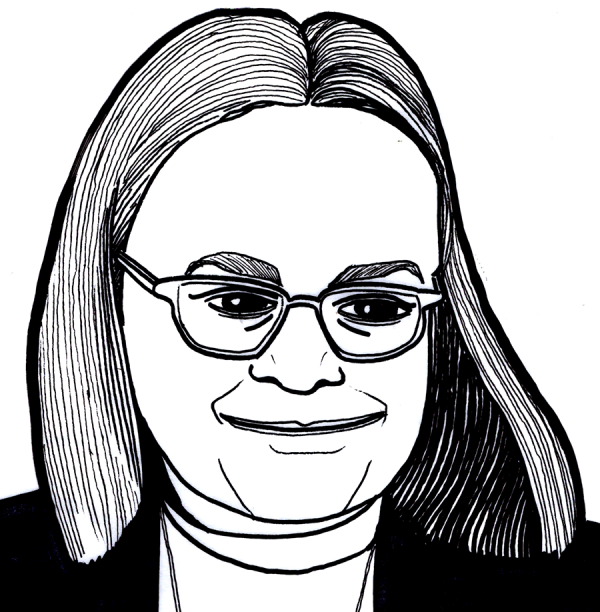

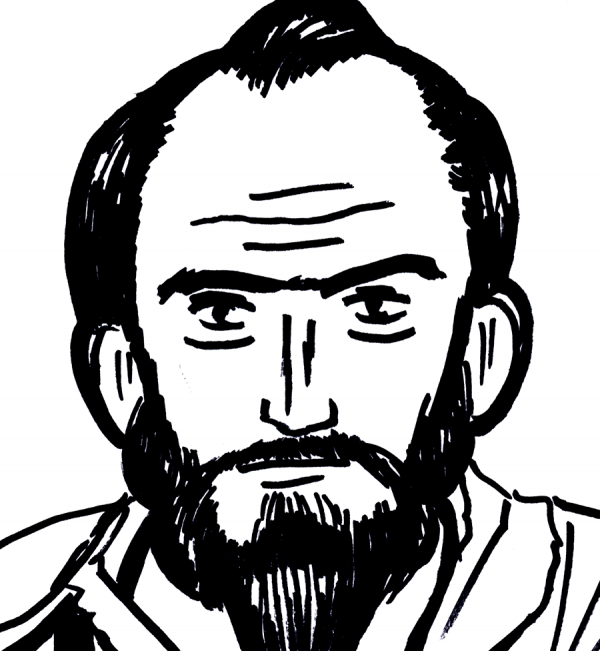

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.

The Old Testament is filled with rules and regulations - reams of them scattered through Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then fleshed out further in Deuteronomy. And Jesus said that He didn't come to abolish the law and the prophets, but to fulfill them.

But not so fast. Even though Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount that nothing would be struck from the the law until "all was accomplished," elsewhere, He said the law and the prophets were proclaimed - past tense - until John, and since then the Gospel has been proclaimed, and everyone's trying to get in.

What's this mean? And how do we fit this in with the fact that Jesus reinterpreted the law all the time? The key comes from this comment by the Apostle Paul: "All things are lawful unto me, but all things are not expedient: all things are lawful for me, but I will not be brought under the power of any."

This phrase is part of a longer explanation by Paul of principles that Jesus demonstrates by example. Both Paul's arguments in Corinthians, and Jesus's frequent rebuttals of the Pharisees, both reject strict applications of the law in favor of appeals to focus on what's good for everyone involved.

I've argued before that Jesus's approach to the law is surprisingly modern and scientific, focusing not on whether someone is strictly obedient to the letter of the law but instead on what various acts do to people. Food passes through the body, and so doesn't make us unclean; but bad thoughts do.

Paul's approach is similar, suggesting that believers resolve disputes not with lawsuits but by arbitration by fellow Christians, and that people who are hurting themselves or others with greed, theft, idolatry, lust, or betrayal are committing sins against their own bodies, which should be sanctified for God.

While both Paul and Jesus condemn various behaviors, we shouldn't take those as an exhaustive list. That's the whole point of the passages: just because something isn't listed on that list doesn't make it right, and conversely, treating Paul or Jesus's examples as Pharisaical commands misses the point.

In Catholic theology, this kind of thinking is called having a "scrupulous conscience" - taking the law as a very literal set of rules which we should follow to the letter, like a roleplayer in a D&D game trying to argue with the gamemaster about whether a given spell would or would not slay a crystal dragon.

But what's printed in the rules of D&D - no matter how specific, regardless of edition - takes second place to what the gamemaster wants to run in his campaign. Similarly, Jesus and Paul want us to develop our own moral imagination, so we can decide, as Jesus did, that it's okay to rescue an ox on the Sabbath.

To unpack this, the laws of the Old Testament are ceremonial, civil and moral. Ceremonial law had to do with Israel's worship, which Christians think pointed ahead to Jesus's coming, became obsolete with his Resurrection, and were arguably - though disputedly - set aside in the Incident at Antioch.

The civil laws of the Old Testament, like the declaration of a jubilee year or the rules for managing slaves, had to do with a society which is very different from the one we have today, and even though they're described as being eternal laws, few Christians think we should apply them all strictly.

Moral laws, like the Ten Commandments and the Great Commandment (which is normally associated with Jesus, but is also present in the Old Testament) retain their force. Not coveting, lying, cheating, stealing, or murdering remain as problematic for us today as they were back in the day.

Jesus's ministry, especially the Sermons of the Mount and the Plain, both adds to and takes away from our understanding of these Old Testament laws. He reinforces some old laws, reinterprets laws like divorce, and provides new examples that set a higher standard.

And yet, He still says the law wasn't going to pass away until everything is fulfilled - a fulfillment which many people take to mean His Resurrection. But I think there's more to it than that. Jesus was God, and taught with authority, so for him to emphasize the law, even as he went beyond it, meant something.

Paul again provides us the key. Perhaps it is true that all things are lawful now, but not everything's good for us. And on the principle that things are not good because the law says so, but that the law says so because things are good for us - we should study the law and use it to guide our understanding.

Yes, we no longer celebrate a jubilee year. Yes, the Jewish dietary restrictions are no longer relevant. Yes, the Biblical attitude to homosexuality is grounded in the prejudices of the cultures at the time, and shows neither a correct understanding of human sexuality nor a Christian respect for individual persons.

But it's worth understanding why these were laws in the first place. It's worthwhile to consider canceling debts. It's worthwhile to consider whether our diets are healthy. It's worthwhile to consider our expression of our sexuality and ask whether it is building up our tearing down our lives and the lives of our partners.

All things may be lawful in the Christian faith if the most important point of Christianity is believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him - but that can be a difficult path, so it's worth reviewing our lives and asking whether we're making it easy to follow Him, or throwing stumbling blocks down for ourselves.

-the Centaur

Pictured: the Apostle Paul, interpolated from three early paintings and the only physical description of him that I know of: of middling size, with scanty hair, large eyes, a long nose, and eyebrows that met.