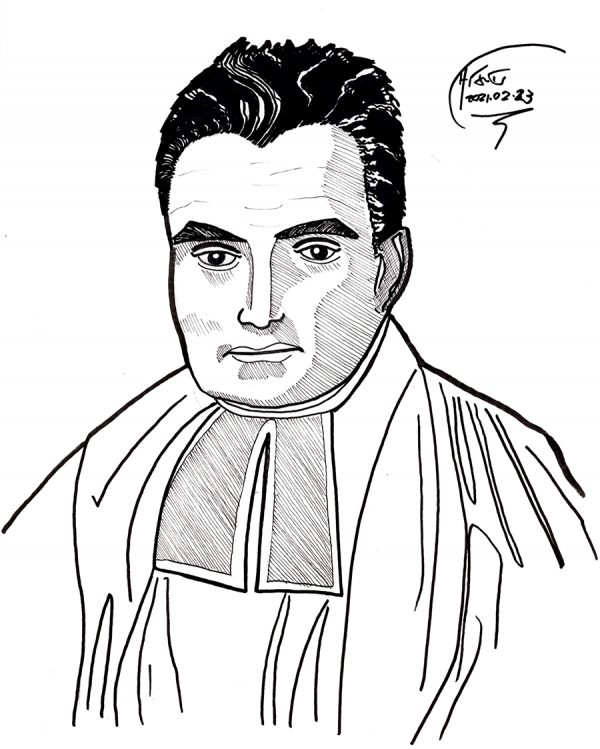

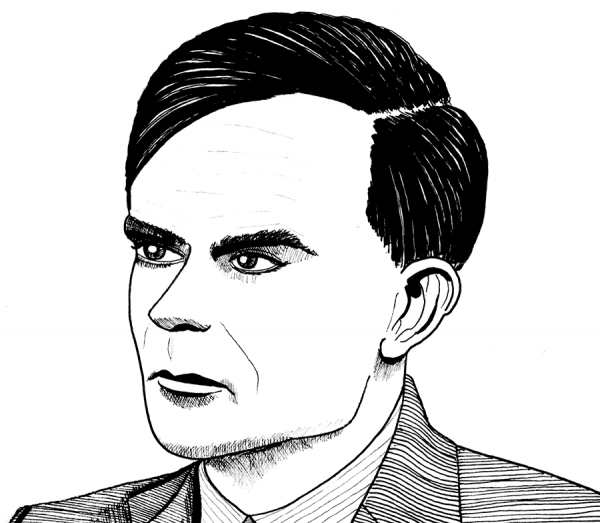

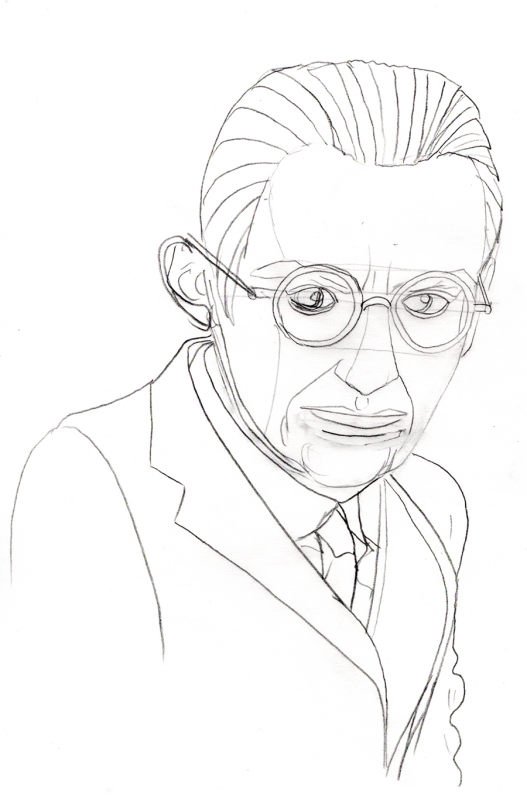

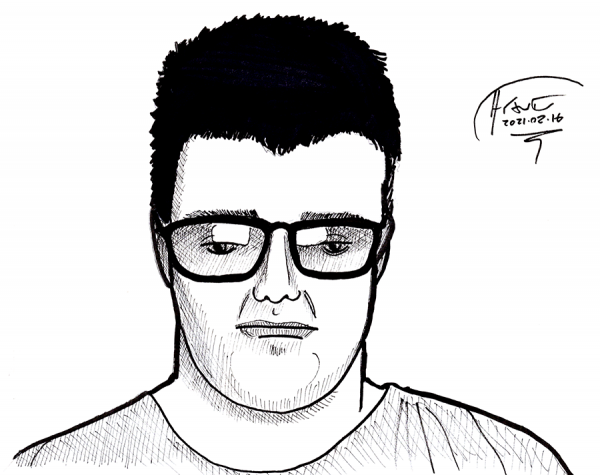

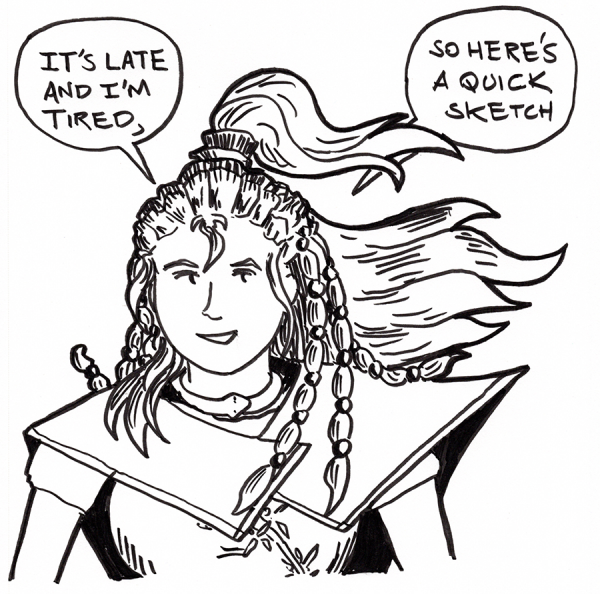

It's late, and I'm tired. Here's an alleged sketch of an alleged picture of Thomas Bayes.

It's late, and I'm tired. Here's an alleged sketch of an alleged picture of Thomas Bayes.

Eyes are off (more visible if you mirror flip the sketch). And I still am making heads too fat.

Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Eyes are off (more visible if you mirror flip the sketch). And I still am making heads too fat.

Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur Words, Art & Science by Anthony Francis

It's late, and I'm tired. Here's an alleged sketch of an alleged picture of Thomas Bayes.

It's late, and I'm tired. Here's an alleged sketch of an alleged picture of Thomas Bayes.

Eyes are off (more visible if you mirror flip the sketch). And I still am making heads too fat.

Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Eyes are off (more visible if you mirror flip the sketch). And I still am making heads too fat.

Still, drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Christianity is a tall ask for many skeptically-minded people, especially if you come from the South, where a lot of folks express Christianity in terms of having a close personal relationship with a person claimed to be invisible, intangible and yet omnipresent, despite having been dead for 2000 years.

On the other hand, I grew up with a fair number of Christians who seem to have no skeptical bones at all, even at the slightest and most explainable of miracles, like my relative who went on a pilgrimage to the Virgin Mary apparitions at Conyers and came back "with their silver rosary having turned to gold."

Or, perhaps - not to be a Doubting Thomas - it was always of a yellowish hue.

Being a Christian isn't just a belief, it's a commitment. Being a Christian is hard, and we're not supposed to throw up stumbling blocks for other believers. So, when I encounter stories like these, which don't sound credible to me and which I don't need to support my faith, I often find myself biting my tongue.

But despite these stories not sounding credible, I do nevertheless admit that they're technically possible. In the words of one comedian, "The Virgin Mary has got the budget for it," and in a world where every observed particle event contains irreducible randomness, God has left Himself the room He needs.

But there's a long tradition in skeptical thought to discount rare events like alleged miracles, rooted in Enlightenment philosopher David Hume's essay "Of Miracles". I almost wrote "scientific thought", but this idea is not at all scientific - it's actually an injection of one of philosophy's worst sins into science.

Philosophy! Who needs it? Well, as Ayn Rand once said: everyone. Philosophy asks the basic questions What is there? (ontology), How do we know it? (epistemology), and What should we do? (ethics). The best philosophy illuminates possibilities for thought and persuasively argues for action.

But philosophy, carving its way through the space of possible ideas, must necessarily operate through arguments, principally verbal arguments which can never conclusively convince. To get traction, we must move beyond argument to repeatable reasoning - mathematics - backed up by real-world evidence.

And that's precisely what was happening right as Hume was working on his essay "Of Miracles" in the 1740's: the laws of probability and chance were being worked out by Hume's contemporaries, some of whom he corresponded with, but he couldn't wait - or couldn't be bothered to learn - their real findings.

I'm not trying to be rude to Hume here, but making a specific point: Hume wrote about evidence, and people claim his arguments are based in rationality - but Hume's arguments are only qualitative, and the quantitative mathematics of probability being developed don't support his idea.

But they can reproduce his idea, and the ideas of the credible believer, in a much sounder framework.

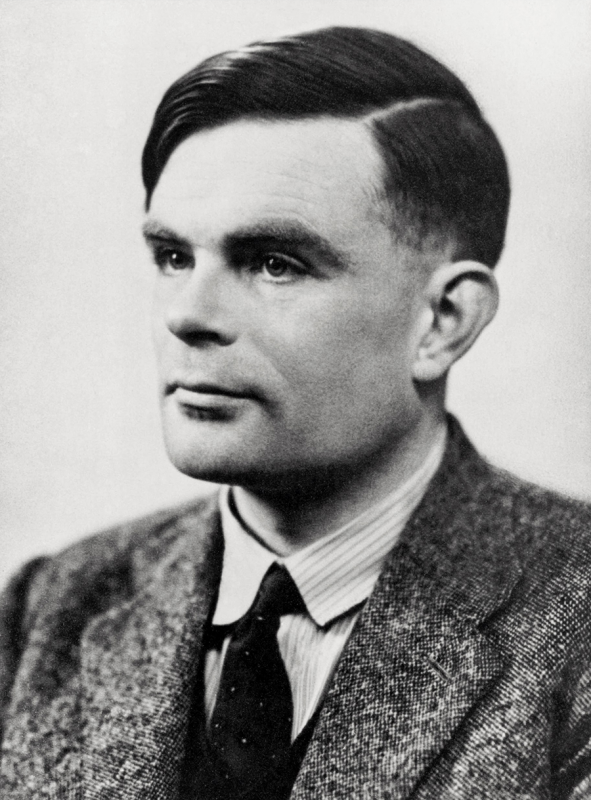

In all fairness, it's best not to be too harsh with Hume, who wrote "Of Miracles" almost twenty years before Reverend Thomas Bayes' "An Essay toward solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances," the work which gave us Bayes' Theorem, which became the foundation of modern probability theory.

If the ground is wet, how likely is it that it rained? Intuitively, this depends on how likely it is that the rain would wet the ground, and how likely it is to rain in the first place, discounted by the chance the ground would be wet on its own, say from a sprinkler system.

In Greenville, South Carolina, it rains a lot, wetting the ground, which stays wet because it's humid, and sprinklers don't run all the time, so a wet lawn is a good sign of rain. Ask that question in Death Valley, with rare rain, dry air - and you're watering a lawn? Seriously? - and that calculus changes considerably.

Bayes' Theorem formalizes this intuition. It tells us the probability of an event given the evidence is determined by the likelihood of the evidence given the event, times the probability of the event, divided by the probability of the evidence happening all by its lonesome.

Since Bayes's time, probabilistic reasoning has been considerably refined. In the book Probability Theory: The Logic of Science, E. T. Jaynes, a twentieth-century physicist, shows probabilistic reasoning can explain cognitive "errors," political controversies, skeptical disbelief and credulous believers.

Jaynes's key idea is that for things like commonsense reasoning, political beliefs, and even interpreting miracles, we aren't combining evidence we've collected ourselves in a neat Bayesian framework: we're combining claims provided to us by others - and must now rate the trustworthiness of the claimer.

In our rosary case, the claimer drove down to Georgia to hear a woman speak at a farmhouse. I don't mean to throw up a stumbling block to something that's building up someone else's faith, but when the Bible speaks of a sign not being given to this generation, I feel like its speaking to us today.

But, whether you see the witness as credible or not, Jaynes points out we also weigh alternative explanations. This doesn't affect judging whether a wet lawn means we should bring an umbrella, but when judging a silver rosary turning to gold, there are so many alternatives: lies, delusions, mistakes.

Jaynes shows, with simple math, that when we're judging a claim of a rare event with many alternative explanations, our trust in the claimer that dominates the change in our probabilistic beliefs. If we trust the claimer, we're likely to believe the claim; if we distrust the claimer, we're likely to mistrust the claim.

What's worse, there's a feedback loop between the trust and belief: if we trust someone, and they claim something we come to believe is likely, our trust in them is reinforced; if we distrust someone, and they claim something we come to believe is not likely, our distrust of them is reinforced too.

It shouldn't take a scientist or a mathematician to realize that this pattern is a pathology. Regardless of what we choose to believe, the actual true state of the world is a matter of natural fact. It did or did not rain, regardless of whether the ground is wet; the rosary did or did not change, whether it looks gold.

Ideally, whether you believe in the claimer - your opinions about people - shouldn't affect what you believe about reality - the facts about the world. But of course, it does. This is the real problem with rare events, much less miracles: they're resistant to experiment, which is our normal way out of this dilemma.

Many skeptics argue we should completely exclude the possibility of the supernatural. That's not science, it's just atheism in a trench coat trying to sell you a bad idea. What is scientific, in the words of Newton, is excluding from our scientific hypotheses any causes not necessary or sufficient to explain phenomena.

A one-time event, such as my alleged phone call to my insurance agent today to talk about a policy for my new car, is strictly speaking not a subject for scientific explanation. To analyze the event, it must be in a class of phenomena open to experiments, such as cell phone calls made by me, or some such.

Otherwise, it's just a data point. An anecdote, an outlier. If you disbelieve me - if you check my cell phone records and argue it didn't happen - scientifically, that means nothing. Maybe I used someone else's phone because mine was out of charge. Maybe I misremembered a report of a very real event.

Your beliefs don't matter. I'll still get my insurance card in a couple of weeks.

So-called "supernatural" events, such as the alleged rosary transmutation, fall into this category. You can't experiment on them to resolve your personal bias, so you have to fall back on your trust for the claimer. But that trust is, in a sense, a personal judgment, not a scientific one.

Don't get me wrong: it's perfectly legitimate to exclude "supernatural" events from your scientific theories - I do, for example. We have to: following Newton, for science to work, we must first provide as few causes as possible, with as many far-reaching effects as possible, until experiment says otherwise.

But excluding rare events from our scientific view of the world forecloses the ability of observation to revise our theories. And excluding supernatural events from our broader view of the world is not a requirement of science, but a personal choice - a deliberate choice not to believe.

That may be right. That may be wrong. What happens, happens, and doesn't happen any other way. Whether that includes the possibility of rare events is a matter of natural fact, not personal choice; whether that includes the possibility of miracles is something you have to take on faith.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Allegedly, Thomas Bayes, though many have little faith in the claimants who say this is him.

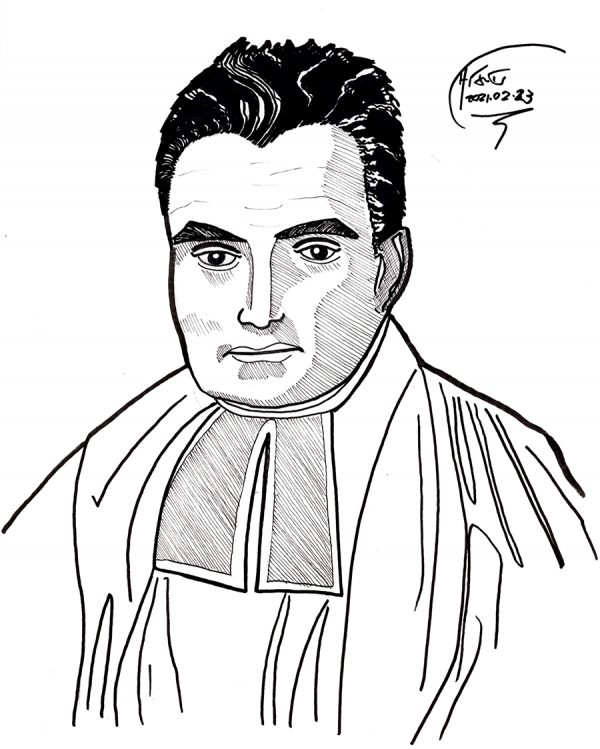

A drawing of St. Thomas Aquinas, trying to make faces look like faces. I don't think I made his face quite fat enough (an opposite problem from previously), and while the relative positions of the eyes are OK, they seem tilted in place. Also, I think I can do better on the ink rendering, in part with better technique, in part by taking more time - though I did deliberately skimp on the time spent on rendering a bit so I could get to bed at an earlier hour tonight - as Saint Aquinas might have said, nothing overmuch!

A drawing of St. Thomas Aquinas, trying to make faces look like faces. I don't think I made his face quite fat enough (an opposite problem from previously), and while the relative positions of the eyes are OK, they seem tilted in place. Also, I think I can do better on the ink rendering, in part with better technique, in part by taking more time - though I did deliberately skimp on the time spent on rendering a bit so I could get to bed at an earlier hour tonight - as Saint Aquinas might have said, nothing overmuch!

Ah well. The fix is ... to keep drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Ah well. The fix is ... to keep drawing every day.

-the Centaur

If you've ever gone to a funeral, watched a televangelist, or been buttonholed by a street preacher, you've probably heard Christianity is all about saving one's immortal soul - by believing in Jesus, accepting the Bible's true teaching on a social taboo, or going to the preacher's church of choice.

(Only the first of these actually works, by the way).

But what the heck is a soul? Most religious people seem convinced that we've got one, some ineffable spiritual thing that isn't destroyed when you die but lives on in the afterlife. Many scientifically minded people have trouble believing in spirits and want to wash their hands of this whole soul idea.

Strangely enough, modern Christian theology doesn't rely too much on the idea of the soul. God exists, of course, and Jesus died for our sins, sending the Holy Spirit to aid us; as for what to do with that information, theology focuses less on what we are and more on what we should believe and do.

If you really dig into it, Christian theology gets almost existential, focusing on us as living beings, present here on the Earth, making decisions and taking consequences. Surprisingly, when we die, our souls don't go to heaven: instead, you're just dead, waiting for the Resurrection and the Final Judgement.

(About that, be not afraid: Jesus, Prince of Peace, is the Judge at the Final Judgment).

This model of Christianity doesn't exclude the idea of the soul, but it isn't really needed: When we die, our decision making stops, defining our relationship to God, which is why it's important to get it right in this life; when it's time for the Resurrection, God has the knowledge and budget to put us back together.

That's right: according to the standard interpretation of the Bible as recorded in the Nicene creed, we're waiting in joyful hope for a bodily resurrection, not souls transported to a purely spiritual Heaven. So if there's no need for a soul in this picture, is there any room for it? What is the idea of the soul good for?

Well, quite a lot, as it turns out.

The theology I'm describing should be familiar to many Episcopals, but it's more properly Catholic, and more specifically, "Thomistic", teachings based on the writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas, a thirteenth-century friar who was recognized - both now and then - as one of the greatest Christian philosophers.

Aquinas was a brilliant man who attempted to reconcile Aristotle's philosophy with Church doctrine. The synthesis he produced was penetratingly brilliant, surprisingly deep, and, at least in part, is documented in books which are packed in boxes in my garage. So, at best, I'm going to riff on Thomas here.

Ultimately, that's for the best. Aquinas's writings predate the scientific revolution, using a scholastic style of argument which by its nature cannot be conclusive, and built on a foundation of topics about the world and human will which have been superseded by scientific findings on physics and psychology.

But the early date of Aquinas's writings affects his theology as well. For example (riffing as best I can without the reference book I want), Aquinas was convinced that the rational human soul necessarily had to be immaterial because it could represent abstract ideas, which are not physical objects.

But now we're good at representing abstract ideas in physical objects. In fact, the history of the past century and a half of mathematics, logic, computation and AI can be viewed as abstracting human thought processes and making them reliable enough to implement in physical machines.

Look, guys - I am not, for one minute, going to get cocky about how much we've actually cracked of the human intellect, much less the soul. Some areas, like cognitive skills acquisition, we've done quite well at; others, like consciousness, are yielding to insights; others, like emotion, are dauntingly intractable.

But it's no longer a logical necessity to posit an intangible basis for the soul, even if practically it turns out to be true. But digging even deeper into Aquinas's notion of a rational soul helps us understand what it is - and why the decisions we make in this life are so important, and even the importance of grace.

The idea of a "form" in Thomistic philosophy doesn't mean shape: riffing again, it means function. The form of a hammer is not its head and handle, but that it can hammer. This is very similar to the modern notion of functionalism in artificial intelligence - the idea that minds are defined by their computations.

Aquinas believed human beings were distinguished from animals by their rational souls, which were a combination of intellect and will. "Intellect" in this context might be described in artificial intelligence terms as supporting a generative knowledge level: the ability to represent essentially arbitrary concepts.

Will, in contrast, is selecting an ideal model of yourself and attempting to guide your actions to follow it. This is a more sophisticated form of decision making than typically used in artificial intelligence; one might describe it as a reinforcement learning agent guided by a self-generated normative model.

What this means, in practice, is that the idea of believing in Jesus and choosing to follow Him isn't simply a good idea: it corresponds directly to the basic functions of the rational soul - intellect, forming an idea of Jesus as a (divinely) good role model, and attempting to follow in His footsteps in our choice of actions.

But the idea of the rational soul being the form of the body isn't just its instantaneous function at one point in time. God exists out of time - and all our thoughts and choices throughout our lives are visible to Him. Our souls are the sum of all of these - making the soul the form of the body over our entire lives.

This means the history of our choices live in God's memory, whether it's helping someone across the street, failing to forgive an irritating relative, going to confession, or taking communion. Even sacraments like baptism that supposedly "leave an indelible spiritual character on the soul" fit in this model.

This model puts the following Jesus, trying to do good and avoid evil, and partaking in sacraments in perspective. God knows what we sincerely believe in our hearts, whether we live up to it or not, and is willing to cut us slack through the mechanisms of worship and grace that add to our permanent record.

Whether souls have a spiritual nature or not - whether they come from the Guf, are joined to our bodies in life, and hang out in Hades after death awaiting reunion at the Resurrection, or whether they simply don't - their character is affected by what we believe, what we do, and how we worship here and now.

And that's why it's important to follow Jesus on this Earth, no matter what happens in the afterlife.

-the Centaur

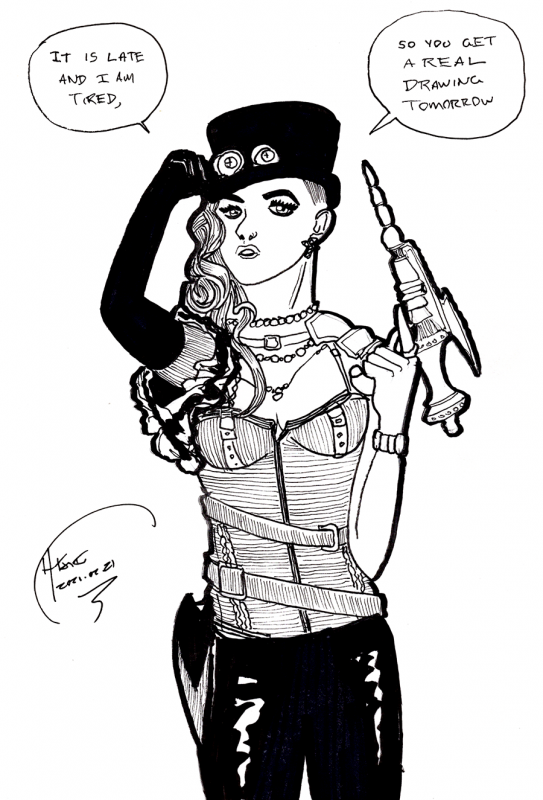

As it says on the tin: trying to get to bed earlier and did a quick sketch. From the cover of a random comic "Gearhearts" in my inspiration pile. The sketch didn't turn out ... terrible ... in fact, the arms almost came out right, and it sort of looks like the cover. But as usual, doing one or two iterations of roughs would have helped the layout of the head and face. My eyes just seem to move around, man.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

As it says on the tin: trying to get to bed earlier and did a quick sketch. From the cover of a random comic "Gearhearts" in my inspiration pile. The sketch didn't turn out ... terrible ... in fact, the arms almost came out right, and it sort of looks like the cover. But as usual, doing one or two iterations of roughs would have helped the layout of the head and face. My eyes just seem to move around, man.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

So I had originally planned on doing a full post each day of Lent, but to make things easier on myself, I decided it was better to respect the Sabbath and treat Sunday as a day of rest.

The Sabbath is a distinctive religious observance as it is about us as much as it is about God.

While we need the grace we get from, say, the Eucharist, the purpose of going to Mass is to worship. But Sunday isn't just about setting aside a day of rest to contemplate God: it's about setting aside a day of rest for ourselves - at least one day out of the week that we can recharge. It's great if we can focus that on God, and that's why the Hebrews had such strict rules about what you could do on Sunday, rules that continue today in the Jewish community and in our former Blue Laws.

But God knows that we need rest and recuperation. The job of living never stops, and it's good for us to take out at least one day to recharge - if we don't make time for it, we can work ourselves to death. As Jesus said, "The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath."

One of the ways I respect Sunday is to avoid shopping unless it's a necessity. Another is to attend Mass (in the before times) or to watch online worship (in these days of the zombie apocalypse). But I'm not altogether good about respecting it, either religiously or personally. And rather than working to 4am again, I instead decided, let's respect the Sabbath, and just share a link of what I'm reading.

Gifts of God for the People of God is a devotional book about the Episcopal Mass by Reverend Furman Buchanan, the priest of St. Peter's, my East Coast church (and where I and my wife were married).

In this book, Buchanan breaks down the parts of the Holy Eucharist and shares explanations of their structure, theological function, and deeper meaning. It's a personal book, in which Buchanan shares experiences from his own life; but it's also good for study groups, with each chapter ending in a series of questions and challenges. My West Coast church, Saint Stephen's in-the-Field, has used it successfully in a Lenten study course, which inspired me to finish this book (which I had already started) for Lent.

I recommend this book. The Holy Eucharist is deeply meaningful to me and I was gratified when I left Catholicism to find a surrogate communion which understands this form of worship as well, if not better.

The former priest of Saint Stephen's, Reverend Ken Wratten, once claimed "Jesus says we can take our Sabbath whenever we want to," pointing out even though he celebrated Holy Eucharist on Sundays, it and Saturday were working days for him, so he took Monday as his actual Sabbath. I wouldn't go quite as far as "whenever we want to" (though there's a lot of evidence backing up Father Ken's claim, including the decision in Acts of the Apostles of the Jerusalem Council that Gentiles don't have to follow the law of Moses) but I would encourage you to take a day of rest in your week whenever you can.

-the Centaur

P.S. Forgive my horrible color scheme on the graphic, I wanted to whip something up quickly in Illustrator and it started fighting me, so I didn't get to do the pass I'd normally do of trying out a variety of schemes in color-scheme-picking-programs to compensate for my color blindness.

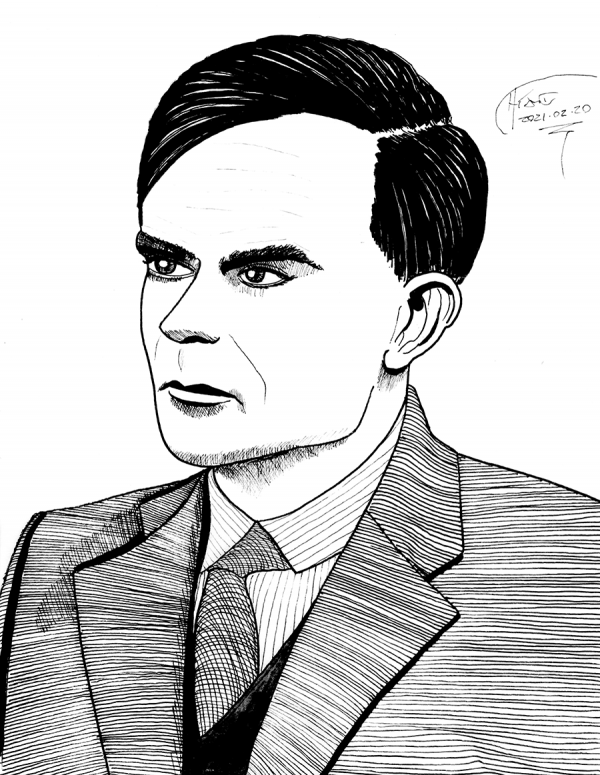

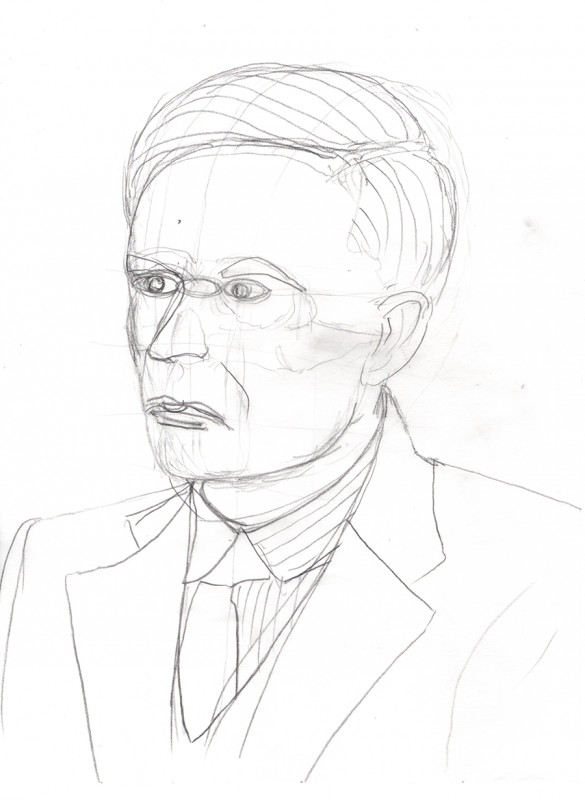

Alan Turing, rendered over my own roughs using several layers of tracing paper. I started with the below rough, in which I tried to pay careful attention to the layout of the face - note the use of the 'third eye' for spacing and curved contour lines - and the relationship of the body, the shoulders and so on.

Alan Turing, rendered over my own roughs using several layers of tracing paper. I started with the below rough, in which I tried to pay careful attention to the layout of the face - note the use of the 'third eye' for spacing and curved contour lines - and the relationship of the body, the shoulders and so on.

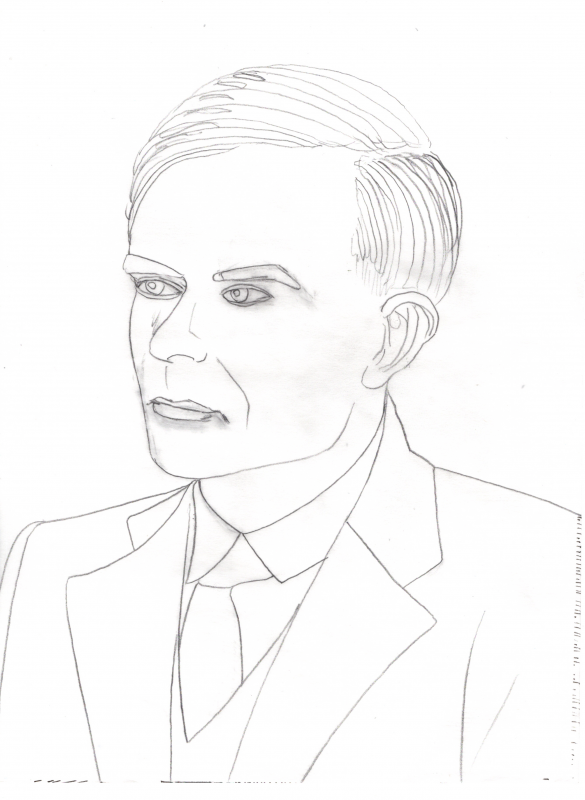

I then corrected that into the following drawing, trying to correct the position and angles of the eyes and mouth - since I knew from previous drawings that I tended to straighten things that were angled, I looked for those flaws and attempted to correct them. (Still screwed up the hair and some proportions).

I then corrected that into the following drawing, trying to correct the position and angles of the eyes and mouth - since I knew from previous drawings that I tended to straighten things that were angled, I looked for those flaws and attempted to correct them. (Still screwed up the hair and some proportions).

This was close enough for me to get started on the rendering. In the end, I like how it came out, even though I flattened the curves of the hair and slightly squeezed the face and pointed the eyes slightly wrong, as you can see if you compare it to the following image from this New Yorker article:

This was close enough for me to get started on the rendering. In the end, I like how it came out, even though I flattened the curves of the hair and slightly squeezed the face and pointed the eyes slightly wrong, as you can see if you compare it to the following image from this New Yorker article:

-the Centaur

-the Centaur

Lent is when Christians choose to give things up or to take things on to reflect upon the death of Jesus. For Lent, I took on this self-referential series about Lent, arguing Christianity is following Jesus, and that following role models are better than following rules because all sets of rules are ultimately incompete.

But how can we choose to follow Jesus? To many Christians, the answer is simple: "free will." At one Passion play (where I played Jesus, thanks to my long hair), the author put it this way: "You are always choose, because no-one can take your will away. You know that, don't you?"

Christians are highly attached to the idea of free will. However, I know a fair number of atheists and agnostics who seem attached to the idea of free will being a myth. I always find this bit of pseudoscence a bit surprising coming from scientifically minded folk, so it's worth asking the question.

Do we have free will, or not?

Well, it depends on what kind of free will we're talking about. Philosopher Daniel Dennett argues at book length that there are many definitions of "free will", only some varieties of which are worth having. I'm not going to use Dennett's breakdown of free will; I'll use mine, based on discussions with people who care.

The first kind of "free will" is undetermined will: the idea that "I", as consciousness or spirit, can make things happen, outside the control of physical law. Well, fine, if you want to believe that: the science of quantum mechanics allows that, since all observable events have unresolvable randomness.

But the science of quantum mechanics also suggests we could never prove that idea scientifically. To see why, look at entanglement: particles that are observed here are connected to particles over there. Say, if momentum is conserved, and two particles fly apart, if one goes left, the other must go right.

But each observed event is random. You can't predict one from the other; you can only extract it from the record by observing both particles and comparing the results. So if your soul is directing your body's choices, we could only tell by recording all the particles of your body and soul and comparing them.

Good luck with that.

The second kind of "free will" is instantaneous will: the idea that "I", at any instant of time, could have chosen to do something differently. It's unlikely we have this kind of free will. First, according to Einstein, simultaneity has no meaning for physically separated events - like the two hemispheres of your brain.

But, more importantly, the idea of an instant is just that - an idea. Humans are extended over time and space; the brain is fourteen hundred cubic centimeters of goo, making decisions over timescales ranging from a millisecond (a neuron fires) to a second and a half (something novel enters consciousness.)

But, even if you accept that we are physically and temporally extended beings, you may still cling to - or reject - an idea of free will: sovereign will, the idea that our decisions, while happening in our brains and bodies, are nevertheless our own. The evidence is fairly good that we have this kind of free will.

Our brains are physically isolated by our skulls and the blood-brain barrier. While we have reflexes, human decision making happens in the neocortex, which is largely decoupled from direct external responses. Even techniques like persuasion and hypnosis at best have weak, indirect effects.

But breaking our decision-making process down this way sometimes drives people away. It makes religious people cling to the hope of undetermined will; it makes scientific people erroneously think that we don't have free will at all, because our actions are not "ours", but are made by physical processes.

But arguing that "because my decisions are made by physical processes, therefore my decisions are not actually mine" requires the delicate dance of identifying yourself with those processes before the comma, then rejecting them afterwards. Either those decision making processes are part of you, or they are not.

If they're not, please go join the religious folks over in the circle marked "undetermined will."

If they are, then arguing that your decisions are not yours because they're made by ... um, the decision making part of you ... is a muddle of contradictions: a mix of equivocation (changing the meaning of terms) and a category error (mistaking your decision making as something separate from yourself).

But people committed to the non-existence of free will sometimes double down, claiming that even if we accept those decision making processes as part of us, our decisions are somehow not "ours" or not "free" because the outcome of our decision making process is still determined by physical laws.

To someone working on Markov decision processes - decision machines - this seems barely coherent.

The foundation of this idea is sometimes called Laplace's demon - the idea that a creature with perfect knowledge of all physical laws and particles and forces would be able to predict the entire history of the universe - and your decisions, so therefore, they're not your decisions, just the outcome of laws.

Too bad this is impossible. Not practically impossible - literally, mathematically impossible.

To see why, we need to understand the Halting Problem - the seemingly simple question of whether we can build a program to tell if any given computer program will halt given any particular input. As basic as this question sounds, Alan Turing proved in the 1930's that this is mathematically impossible.

The reason is simple: if you could build an analysis program which could solve this problem, you could feed itself to itself - wrapped in a loop that went forever if the original analysis program halts, and halts if it ran forever. No matter what answer it produces, it leads to a contradiction. The program won't work.

This idea seems abstract, but its implications are deep. It applies to not just computer programs, but to a broad class of physical systems in a broad class of universes. And it has corollaries, the most important being: you cannot predict what any arbitrary given algorithm will do without letting the algorithm do it.

If you could, you could use it to predict whether a program would halt, and therefore, you could solve the Halting Problem. That's why Laplace's Demon, as nice a thought experiment as it is, is slain by Turing's Machine. To predict what you would actually do, part of the demon would have to be identical to you.

Nothing else in the universe - nothing else in a broad class of universes - can predict your decisions. Your decisions are made in your own head, not anyone else's, and even though they may be determined by physical processes, the physical processes that determine them are you. Only you can do you.

So, you have sovereign will. Use it wisely.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Alan Turing, of course.

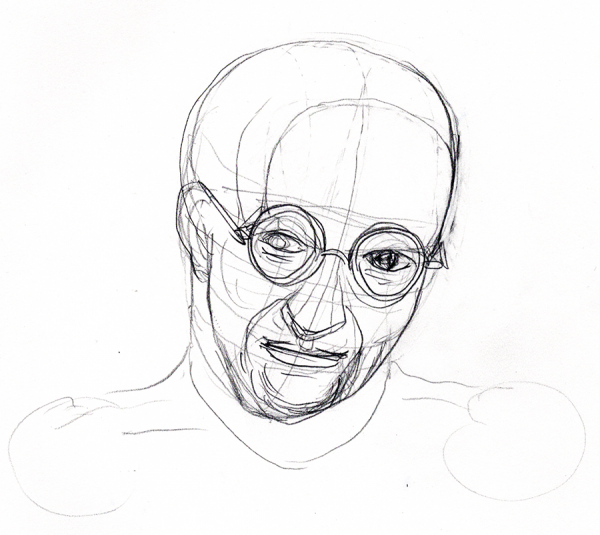

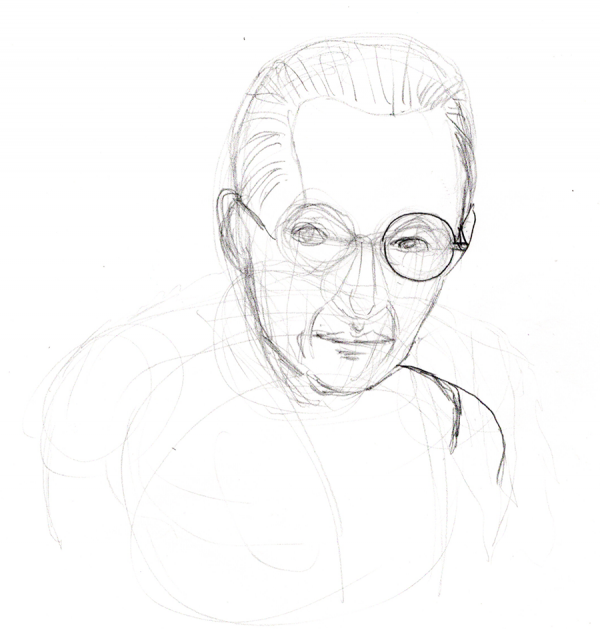

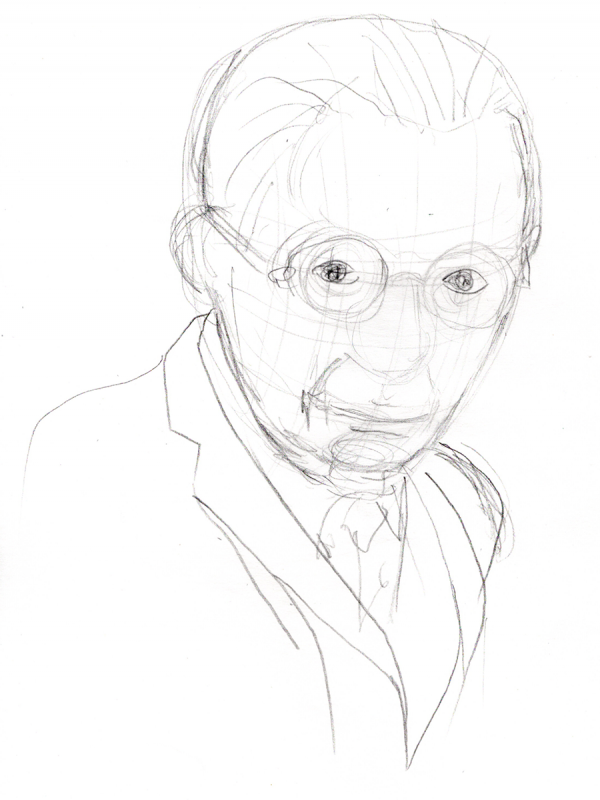

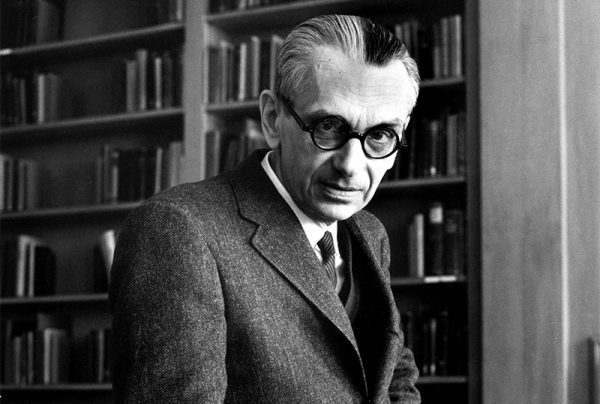

Full drawing of Kurt Gödel from today's Lent entry. Like previous exercises, I traced my own roughs, using a variety of Micron pens. As for whether the face looks like a face ... ehh, mostly? Though I am still apparently inflating noses and cartoonishly exaggerating heads with respect to bodies, making Kurt here look like an extra from Men in Black (thinking of Tommy Lee Jone's comically oversized head).

Where I departed here was throwing out several intermediate roughs, as I did on Day 054. I started off with a normal 2B pencil sketch on Strathmore and quickly decided that it was going nowhere:

Full drawing of Kurt Gödel from today's Lent entry. Like previous exercises, I traced my own roughs, using a variety of Micron pens. As for whether the face looks like a face ... ehh, mostly? Though I am still apparently inflating noses and cartoonishly exaggerating heads with respect to bodies, making Kurt here look like an extra from Men in Black (thinking of Tommy Lee Jone's comically oversized head).

Where I departed here was throwing out several intermediate roughs, as I did on Day 054. I started off with a normal 2B pencil sketch on Strathmore and quickly decided that it was going nowhere:

Rather than starting over on Strathmore, I switched to tracing paper and tried the following. In some ways I like this drawing more than some of the later sketches - it captures a bit of Gödel's distinctive face - but I rapidly realized I'd again got the macro-architecture of the sketch wrong, shoulders ending up in the wrong place and such. Also, though you can't tell from this crop, it was too small on the page.

Rather than starting over on Strathmore, I switched to tracing paper and tried the following. In some ways I like this drawing more than some of the later sketches - it captures a bit of Gödel's distinctive face - but I rapidly realized I'd again got the macro-architecture of the sketch wrong, shoulders ending up in the wrong place and such. Also, though you can't tell from this crop, it was too small on the page.

So I started over, producing the following sketch. The face is a bit off here, too wide, looking something like a cross between Mr. Magoo and Joe Biden (if either wore glasses). But I could tell the overall layout was good this time - things were roughly in the right place, and could be corrected with some effort.

So I started over, producing the following sketch. The face is a bit off here, too wide, looking something like a cross between Mr. Magoo and Joe Biden (if either wore glasses). But I could tell the overall layout was good this time - things were roughly in the right place, and could be corrected with some effort.

I traced the following directly over the previous sketch, correcting for the shape of the nose and face, but keeping the parts that seemed like they were a good fit. This sketch wasn't perfect either, but it was close enough for me to get started - I had blogposts to write! - and led to the drawing at the top of the page, which I traced over the below drawing, making a few more corrections and allowances for rendering.

I traced the following directly over the previous sketch, correcting for the shape of the nose and face, but keeping the parts that seemed like they were a good fit. This sketch wasn't perfect either, but it was close enough for me to get started - I had blogposts to write! - and led to the drawing at the top of the page, which I traced over the below drawing, making a few more corrections and allowances for rendering.

The original? Below, from a Nature article (Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/ LIFE Picture Coll./Getty).

The original? Below, from a Nature article (Credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/ LIFE Picture Coll./Getty).

My drawing ... sorta looks like the guy? I still think I can do better, particularly in making faces longer and narrower (a problem I had with the Eleventh Doctor as well). But still ...

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

My drawing ... sorta looks like the guy? I still think I can do better, particularly in making faces longer and narrower (a problem I had with the Eleventh Doctor as well). But still ...

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Yesterday I claimed that Christianity was following Jesus - looking at him as a role model for thinking, judging, and doing, stepping away from rules and towards principles, choosing good outcomes over bad ones and treating others like we wanted to be treated, and ultimately emulating what Jesus would do.

But it's an entirely fair question to ask, why do we need a role model to follow? Why not have a set of rules that guide our behavior, or develop good principles to live by? Well, it turns out it's impossible - not hard, but literally mathematically impossible - to have perfect rules, and principles do not guide actions. So a role model is the best tool we have to help us build the cognitive skill of doing the right thing.

Let's back up a bit. I want to talk about what rules are, and how they differ from principles and models.

In the jargon of my field, artificial intelligence, rules are if-then statements: if this, then do that. They map a range of propositions to a domain of outcomes, which might be actions, new propositions, or edits to our thoughts. There's a lot of evidence that the lower levels of operation of our minds is rule-like.

Principles, in contrast, are descriptions of situations. They don't prescribe what to do; they evaluate what has been done. The venerable artificial intelligence technique of generate-and-test - throw stuff on the wall to see what sticks - depends on "principles" to evaluate whether the outcomes are good.

Models are neither if-then rules nor principles. Models predict the evolution of a situation. Every time you play a computer game, a model predicts how the world will react to your actions. Every time you think to yourself, "I know what my friend would say in response to this", you're using a model.

Rules, of a sort, may underly our thinking, and some of our most important moral precepts are encoded in rules, like the Ten Commandments. But rules are fundamentally limited. No matter how attached you are to any given set of rules, eventually, those rules can fail you, and you can't know when.

The iron laws behind these fatal flaws are Gödel's incompleteness theorems. Back in the 1930's, Kurt Gödel showed any set of rules sophisticated enough to handle basic math would either fail to find things that were true, or would make mistakes - and, worse, could never prove that they were consistent.

Like so many seemingly abstract mathematical concepts, this has practical real-world implications. If you're dealing with anything at all complicated, and try to solve your problems with a set of rules, either those rules will fail to find the right answers, or will give the wrong answers, and you can't tell which.

That's why principles are better than rules: they make no pretensions of being a complete set of if-then rules that can handle all of arithmetic and their own job besides. They evaluate propositions, rather than generating them, they're not vulnerable to the incompleteness result in the same way.

How does this affect the moral teachings of religion? Well, think of it this way: God gave us the Ten Commandments (and much more) in the Old Testament, but these if-then rules needed to be elaborated and refined into a complete system. This was a cottage industry by the time Jesus came on the scene.

Breaking with the rule-based tradition, Jesus gave us principles, such as "love thy neighbor as thyself" and "forgive as you wish to be forgiven" which can be used to evaluate our actions. Sometimes, some thought is required to apply them, as in the case of "Is it lawful to do good or evil on the Sabbath?"

This is where principles fail: they don't generate actions, they merely evaluate them. Some other process needs to generate those actions. It could be a formal set of rules, but then we're back at square Gödel. It could be a random number generator, but an infinite set of monkeys will take forever to cross the street.

This is why Jesus's function as a role model - and the stories about Him in the Bible - are so important to Christianity. Humans generate mental models of other humans all the time. Once you've seen enough examples of someone's behavior, you can predict what they will do, and act and react accordingly.

The stories the Bible tells about Jesus facing moral questions, ethical challenges, physical suffering, and even temptation help us build a model of what Jesus would do. A good model of Jesus is more powerful than any rule and more useful than any principle: it is generative, easy to follow, and always applicable.

Even if you're not a Christian, this model of ethics can help you. No set of rules can be complete and consistent, or even fully checkable: rules lawyering is a dead end. Ethical growth requires moving beyond easy rules to broader principles which can be used to evaluate the outcomes of your choices.

But principles are not a guide to action. That's where role models come in: in a kind of imitation-based learning, they can help guide us by example until we've developed the cognitive skills to make good decisions automatically. Finding role models that you trust can help you grow, and not just morally.

Good role models can help you decide what to do in any situation. Not every question is relevant to the situations Jesus faced in ancient Galilee! For example, when faced with a conundrum, I sometimes ask three questions: "What would Jesus do? What would Richard Feynman do? What would Ayn Rand do?"

These role models seem far apart - Ayn Rand, in particular, tried to put herself on the opposite pole from Jesus. But each brings unique mental thought processes to the table - "Is this doing good or evil?" "You are the easiest person for yourself to fool" and "You cannot fake reality in any way whatsoever."

Jesus helps me focus on what choices are right. Feynman helps me challenge my assumptions and provides methods to test them. Rand is benevolent, but demands that we be honest about reality. If two or three of these role models agree on a course of action, it's probably a good choice.

Jesus was a real person in a distant part of history. We can only reach an understanding of who Jesus is and what He would do by reading the primary source materials about him - the Bible - and by analyses that help put these stories in context, like religious teachings, church tradition, and the use of reason.

But that can help us ask what Jesus would do. Learning the rules are important, and graduating beyond them to understand principles is even more important. But at the end of the day, we want to do the right thing, by following the lead of the man who asks, "Love thy neighbor as thyself."

-the Centaur

Pictured: Kurt Gödel, of course.

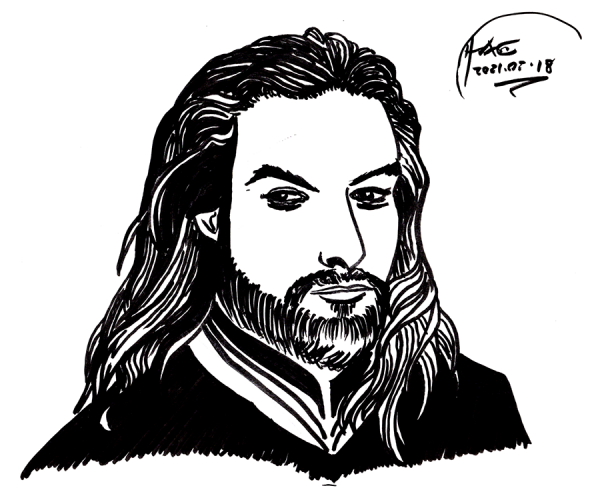

Quick sketch of Jason Momoa, the reference for my Jesus sketch earlier. That sketch I started from scratch and only loosely used Momoa's mug to touch up some details; it still didn't come out great. Also, I sketched it on the Cintiq in Photoshop. This is also a quick sketch, but on Strathmore 9x12 with a Faber- Castell "B" Pitt Artist Pen Brush - and just that. Given that it was pushing 4am, I wanted to try using a simpler technique, to see how much I could extract out of just one pen (well, brush) for the render. As for how much the face looks like a face ...

Quick sketch of Jason Momoa, the reference for my Jesus sketch earlier. That sketch I started from scratch and only loosely used Momoa's mug to touch up some details; it still didn't come out great. Also, I sketched it on the Cintiq in Photoshop. This is also a quick sketch, but on Strathmore 9x12 with a Faber- Castell "B" Pitt Artist Pen Brush - and just that. Given that it was pushing 4am, I wanted to try using a simpler technique, to see how much I could extract out of just one pen (well, brush) for the render. As for how much the face looks like a face ...

Not ... terrible, but the proportions are still off, and my sketch gave him way too big a schnoz. Jason Momoa is a good looking guy, and unfortunately my sketch makes him look more like a rejected villain from the Princess Bride. Ah well. Perhaps I'll eventually be able to sketch good looking superheroes ...

... if I keep drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Not ... terrible, but the proportions are still off, and my sketch gave him way too big a schnoz. Jason Momoa is a good looking guy, and unfortunately my sketch makes him look more like a rejected villain from the Princess Bride. Ah well. Perhaps I'll eventually be able to sketch good looking superheroes ...

... if I keep drawing every day.

-the Centaur

tl;dr: Christianity is following Jesus.

I know, I know, that seems obvious: His name is on the tin. Jesus Christ - Christianity, right? But it's surprising to me sometimes how non-obvious that is, or how often people who claim to be Christians don't seem to be putting that first.

I grew up in the South. I've seen fundamentalists claim to be Bible-worshipping Christians; what about Jesus-following Christians? I've seen Baptists challenge each other about following doctrine - what about following Jesus? I've seen Catholics rant about following Church dogma - how about following Jesus?

Now, a fundamentalist might tell you that you need to turn to the Bible to know Jesus, and I've had Baptists tell me there's only one true interpretation of the Bible which determines the correct doctrines, which sounds very Catholic in its curation of official doctrines collated as dogma.

But in the violent arguments that sometimes follow, the participants rarely seem to come back to the name Jesus. They'll argue that you must read your Bible, or that belief in evolution makes you an atheist, or that breaking from church teachings cuts you off from grace and makes you an apostate.

Where is Jesus in all that? He's not.

Even in church board meetings, when we're worrying about our tight budgets, supporting our ministries, and our fellowships with other churches, I frequently find that the discussion rarely comes back to Jesus. Even though drawing people to Christ is in our mission statement, we get bogged down with details.

When it's my turn to speak, I bring up Jesus's name in a way that's relevant, and let the Spirit guide me through the rest. Think of it as a high-powered version of What Would Jesus Do, but instead leading to questions like, "If this budget exists to draw people to Jesus, how would He want us to use it?"

Which leads to the question, what does following Jesus mean?

That's a big question, but first off, Jesus says "Be not afraid!" Actually, he says that quite a bit, more than a dozen times in the New Testament. He also says, "Repent!" over a dozen times - meaning, change your mind to change the way you live, breaking your commitment to the things you're doing wrong.

Change is scary, because we're often surprisingly committed to the things that we're doing that are wrong. We find it hard to give them up, which is one reason why Lent is important - it asks us to give things up temporarily, to help us build up the muscles we need to quit things forever.

So following Jesus involves fearless repentance. But what is wrong, and how should we turn to the right, and how do we manage the scary thought that the things we're doing may be things we should abandon? Well, to me, the reason Christianity is named after Jesus is that He's the answer to all three questions.

Jesus Christ isn't the typical "first name - last name" combination familiar to modern Western audiences. The "Jesus" part is His actual name, but in that's actually a twice-removed transliteration to English through Greek of the original Hebrew "Yeshua", which roughly means "God saves".

The "Christ" part is a title - which is why sometimes you hear of the man referred to as "Jesus, son of Joseph from Nazareth" as "Christ Jesus". Christ originally meant "the anointed one", but in Christian theology it came to mean the "messiah", or Savior.

So Jesus Christ means God saves, twice over. But what does that mean? Jesus saves who from what?

Well, He saves us from the consequences of our bad choices. In Christian theology, our sins merit punishment, but Jesus's death on the cross was a sacrifice which blots all that out - so there's no need to be trapped in sin for fear that you won't be forgiven: repentance comes at no cost, thanks to Jesus.

That manages the fear, but what are we doing wrong? Jesus said the two greatest commandments are loving the one God and loving your neighbor as yourself. In practice, I think this means putting nothing above doing the right thing, and making sure we treat others as we wish to be treated.

Jesus says all religious laws are ultimately derived from these foundations. This gets tricky in practice, because there are many rules written down in the Bible and put forth by churches and passed into law by the hands of man, and its hard to follow them all. In fact, sometimes they don't even seem to be just.

That's where Jesus comes in again. Over and over in the New Testament, people ask questions of Jesus about how different rules and laws conflict. Again and again, He responds not by picking one rule over the other, but by asking the question of what principles are at stake, and what outcome is good?

That's how Jesus outwitted the challengers who asked whether it was legal to heal someone on the Sabbath: "Which is lawful on the Sabbath, to do good or to do evil, to save life or destroy it?" Again and again, Jesus asks basic questions like these, using an almost scientific mindset applied to ethics.

In fairness to my Christian brethren, I got to this understanding by reading the Bible to find out who Jesus was, by debating doctrine with my Baptist friends, by learning Catholic dogma, and by ultimately coming to my own conclusions in the Episcopal tradition, combining scripture, tradition and reason together.

But I think these principles are universal. Whether you're a Christian or not, you can look honestly at what you're doing, decide whether it's right or wrong, and put aside the wrong in favor of the right. You shouldn't be afraid to do so, because choosing to do the right thing is its own reward.

There always is a better way, and you're always free to choose it.

To me, that's following Jesus, and is the bedrock principle of Christianity. Of course, there's more: Christians believe in Jesus as a divine member of the Trinity, one God in three Persons. But I don't think the principles of Christianity are true because Jesus said them; I think He said them because they're true.

-the Centaur

So, today's exercise was something very difficult for me: abandoning a failed rough and starting over.

You see, many artists that I know will get sucked into perfecting a drawing that has some core flaw in its bones - this is something I ran into with my Batman cover page. I know one artist who has worked over a handful of difficult paintings for literally 2-3 years ... but who can produce dozens of new paintings for a show on the drop of a hat. But it's hard emotionally to let go the investment in a partially finished piece.

This is tied up with the Sunken Cost Fallacy Fallacy, the false idea that if you've decided a venture has failed you should cut your losses despite your prior investment in it. This is based on the very real ideas of sunk costs - costs expended that cannot be recovered - which should not be factored into rational decisions the same way that we should prospective costs - costs that can be avoided by taking action. The "Sunken Cost Fallacy" comes in when people don't cut their losses in a failed venture.

The "Fallacy Fallacy" part kicks in because in the real world costs do not become sunk as a result of your decisions. When a self-proclaimed "decider"(1) chooses to proclaim that a project is a failure, the value invested in the project doesn't magically become nonrecoverable based on that decision and the classical Sunken Cost Fallacy does not apply. I have seen a private company literally throw away a two million dollar investment for a dollar because the owner didn't want to deal with it anymore.

Fortunately, most artists are better businessmen than that. Deep down, they know any painting could be the ONE that gets them seen; deeper down, each painting is an expression of their creativity. Even if the painting has flaws, one never knows whether the piece will be fixable, even ultimately excel. I have seen paintings go through years of work and many difficulties, only to finally turn up amazing. Drawings, paintings and novels are like investments in that way, always tantalizing us with their future potential.

But, deep down, I feel like it's possible to do better than that. That by painting or drawing more, and being more ruthless earlier in the process, that it's possible to recognize wrong turns and truly sunken costs and to start over. Once a huge canvas has covered with paint over many months, or a large manuscript has been filled with words over an equal period of time, it represents an investment in images and ideas that can potentially be salvaged ... but a sketch or outline, now, that you can throw out straightaway.

You may not get the thirty minutes doing the sketch back, but at least you'll be starting in a better place.

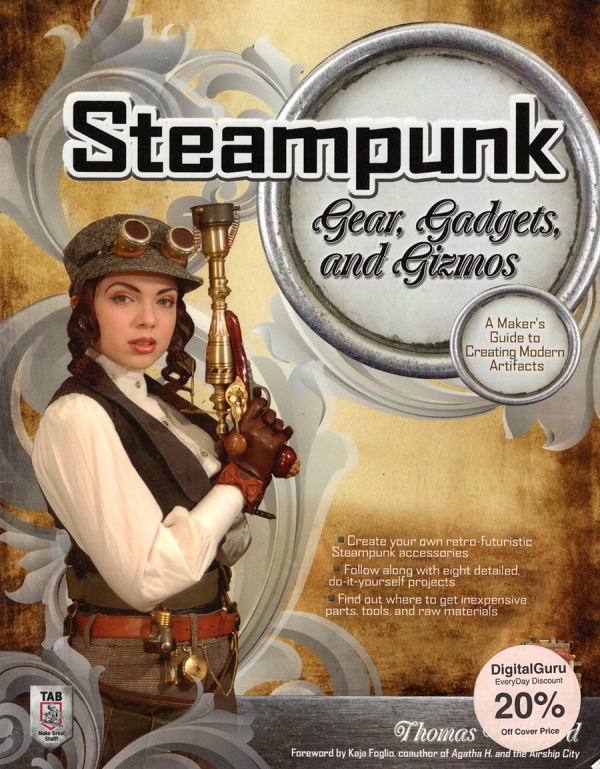

In my case, I was starting here, the cover for Steampunk Gear, Gadgets and Gizmos I had lying about:

So, today's exercise was something very difficult for me: abandoning a failed rough and starting over.

You see, many artists that I know will get sucked into perfecting a drawing that has some core flaw in its bones - this is something I ran into with my Batman cover page. I know one artist who has worked over a handful of difficult paintings for literally 2-3 years ... but who can produce dozens of new paintings for a show on the drop of a hat. But it's hard emotionally to let go the investment in a partially finished piece.

This is tied up with the Sunken Cost Fallacy Fallacy, the false idea that if you've decided a venture has failed you should cut your losses despite your prior investment in it. This is based on the very real ideas of sunk costs - costs expended that cannot be recovered - which should not be factored into rational decisions the same way that we should prospective costs - costs that can be avoided by taking action. The "Sunken Cost Fallacy" comes in when people don't cut their losses in a failed venture.

The "Fallacy Fallacy" part kicks in because in the real world costs do not become sunk as a result of your decisions. When a self-proclaimed "decider"(1) chooses to proclaim that a project is a failure, the value invested in the project doesn't magically become nonrecoverable based on that decision and the classical Sunken Cost Fallacy does not apply. I have seen a private company literally throw away a two million dollar investment for a dollar because the owner didn't want to deal with it anymore.

Fortunately, most artists are better businessmen than that. Deep down, they know any painting could be the ONE that gets them seen; deeper down, each painting is an expression of their creativity. Even if the painting has flaws, one never knows whether the piece will be fixable, even ultimately excel. I have seen paintings go through years of work and many difficulties, only to finally turn up amazing. Drawings, paintings and novels are like investments in that way, always tantalizing us with their future potential.

But, deep down, I feel like it's possible to do better than that. That by painting or drawing more, and being more ruthless earlier in the process, that it's possible to recognize wrong turns and truly sunken costs and to start over. Once a huge canvas has covered with paint over many months, or a large manuscript has been filled with words over an equal period of time, it represents an investment in images and ideas that can potentially be salvaged ... but a sketch or outline, now, that you can throw out straightaway.

You may not get the thirty minutes doing the sketch back, but at least you'll be starting in a better place.

In my case, I was starting here, the cover for Steampunk Gear, Gadgets and Gizmos I had lying about:

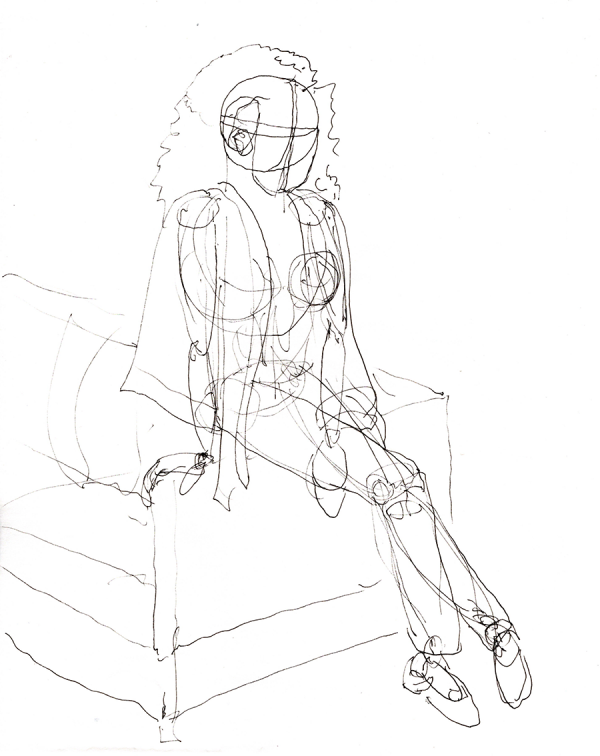

I started what I intended to be a quick sketch, and got partway into the roughs ...

I started what I intended to be a quick sketch, and got partway into the roughs ...

... when I decided that the shape of the face was off - and the proportions of the arm were even further off. I started to fix it - you can see a few doubled features like eyes and lips in there - but I decided - ha, decided - no, stop, STOP Anthony, this rough is too far gone.

Start over, and look more closely at what you see this time.

That led to the drawing at the top of the entry. There were still problems with the finished piece - I am continuing to have trouble with tilting heads the wrong way, and something went wrong with the shape of the arm, leading to a too-narrow, too-long wrist - but the bones of the sketch were so much better than the first attempt that it was easy to finish the drawing.

And thus, keep up drawing every day.

-the Centaur

(1) I'm not bitter.

... when I decided that the shape of the face was off - and the proportions of the arm were even further off. I started to fix it - you can see a few doubled features like eyes and lips in there - but I decided - ha, decided - no, stop, STOP Anthony, this rough is too far gone.

Start over, and look more closely at what you see this time.

That led to the drawing at the top of the entry. There were still problems with the finished piece - I am continuing to have trouble with tilting heads the wrong way, and something went wrong with the shape of the arm, leading to a too-narrow, too-long wrist - but the bones of the sketch were so much better than the first attempt that it was easy to finish the drawing.

And thus, keep up drawing every day.

-the Centaur

(1) I'm not bitter.

Twenty-Twenty, man! A year that sucked, followed by a year that sounds like "Twenty-Twenty Won" (and don't get me started on the third act of the trilogy, "Twenty-Twenty Too" ... not even the Sharknado team could have come up with the plots of the Twenty-Twenty franchise).

As we're recovering from last year - recovering from January of THIS year - the normal rhythms of life have been quietly reasserting themselves. Elections are followed by inaugurations. Winter weather will soon be followed by spring plantings. And Ash Wednesday will soon be followed by Easter.

"Two thousand twenty-one" in our calendar marks two millennia, give or take, since the birth of Jesus, the founder of Christianity, the world's largest religion. Today, "Ash Wednesday" in the Christian calendar marks the beginning of Lent, the solemn observance of Jesus's Crucifixion.

You can follow the links to find out what Lent and Ash Wednesday and Christianity and the Crucifixion mean to other people. But what I want to tell you about what they mean to me. Lent has always been a time for me to reconnect with my own faith, and each year I do that a slightly different way.

Lent celebrates Jesus's Resurrection, when He turned death into new life - and turned failure as a regional preacher into success at creating a world-spanning church. Prior to His death, Jesus went into the wilderness and was tempted for 40 days, which Christians emulate by giving things up for Lent.

Well, the pandemic has knocked a loop for most of the things that I normally give up for Lent: giving up meat (I'm mostly eating vegan), giving up alcohol (I try to avoid drinking at home), giving up soda (long story). While I've been blessed to not be starving this pandemic, it's still been a time of deprivation.

That got me thinking. I once heard someone suggest, "Give up Something Bad for Lent!" (as opposed to the normal giving up something good). Well, what about flipping it on its head entirely? What about, rather than giving up something bad for Lent, why not take on something good for Lent?

Normally I try not to talk about what I've given up for Lent - on the principle Jesus puts forth in Matthew 6:5 that praying for show is its own reward - that is, no reward at all. But again, flipping it on its head entirely, if I've taken on something good for Lent, why not take on something to share with everyone?

So, like my Drawing Every Day series, for the next forty days, I'm going to blog about what Lent means to me. And the key meaning of Lent, for me, is reconnection - dare I say, Resurrection? Christianity is supposed to be a "catholic" religion - catholic, meaning "universal," a religion for everyone.

The universality of Christianity means that it's for everyone. Everyone has free will. Everyone can screw up. Everyone can feel a loss of connection to God. And Jesus's role was to light the way - taking on our screwups in His death, and washing them away in His Resurrection.

SO, in the coming weeks, I hope to show you what I'm trying to connect back to every Lent. For some of you, this will be bread and butter; for others, this will be alien. Regardless, I hope I'm going to be able to leave you with an understanding of why every year I walk the path of Lent towards the Resurrection.

-the Centaur

Sketched faces from tonight's Write to the End session. No comparison photos, because my fellow writers deserve their privacy (especially since I used a screen shot which caught one of them in a scowl and the other while speaking), but I know enough to rate this as "meh". The face above expands the hair and squashes the lower face - same mistake from Spock yesterday, so it wasn't just head tilt - and a little of that's going on with the face below, though the biggest problem there is the mouth is too narrow.

Sketched faces from tonight's Write to the End session. No comparison photos, because my fellow writers deserve their privacy (especially since I used a screen shot which caught one of them in a scowl and the other while speaking), but I know enough to rate this as "meh". The face above expands the hair and squashes the lower face - same mistake from Spock yesterday, so it wasn't just head tilt - and a little of that's going on with the face below, though the biggest problem there is the mouth is too narrow.

The ultimate goal of these drawings is to rekindle my love of my art and to sharpen my abilities to the point where I can once again resume f@nu fiku, finish my science fiction comic projects, and move on to other comic ideas I have scattered through my notebooks.

My inspiration for this project comes from a young psychology student who took a drawing class just as he was about to graduate, and, inspired, put off medical school with a crash course to break in to the comics field in just one year. He succeeded, and his name is Jim Lee, now Publisher of DC Comics.

I don't expect success in a year - I have a day job and a novel-writing career, not to mention a family - nor do I want to be Jim Lee. But I do want to be Anthony Francis. And Anthony Francis, by day, builds intelligent machines and emotional robots, and by night writes science fiction and draws comic books.

I've built intelligent machines. I've worked on emotional robots. I've written and published science fiction. But the comic books, other than my short stint on f@nu fiku, have eluded me. Connecting thoughts and images is a huge part of my creative expression, yet I seem to have let it fall by the wayside.

But I'm bringing it back by drawing every day.

-the Centaur

The ultimate goal of these drawings is to rekindle my love of my art and to sharpen my abilities to the point where I can once again resume f@nu fiku, finish my science fiction comic projects, and move on to other comic ideas I have scattered through my notebooks.

My inspiration for this project comes from a young psychology student who took a drawing class just as he was about to graduate, and, inspired, put off medical school with a crash course to break in to the comics field in just one year. He succeeded, and his name is Jim Lee, now Publisher of DC Comics.

I don't expect success in a year - I have a day job and a novel-writing career, not to mention a family - nor do I want to be Jim Lee. But I do want to be Anthony Francis. And Anthony Francis, by day, builds intelligent machines and emotional robots, and by night writes science fiction and draws comic books.

I've built intelligent machines. I've worked on emotional robots. I've written and published science fiction. But the comic books, other than my short stint on f@nu fiku, have eluded me. Connecting thoughts and images is a huge part of my creative expression, yet I seem to have let it fall by the wayside.

But I'm bringing it back by drawing every day.

-the Centaur

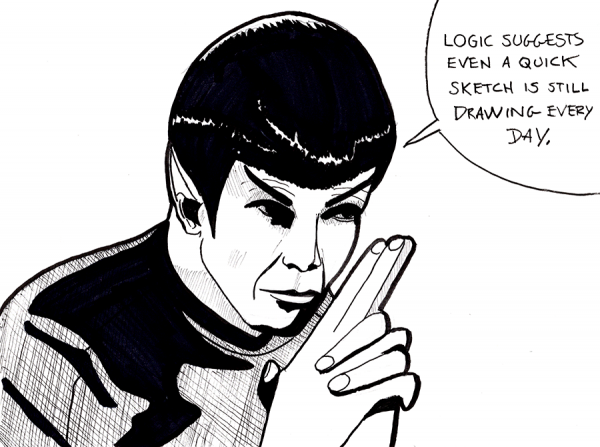

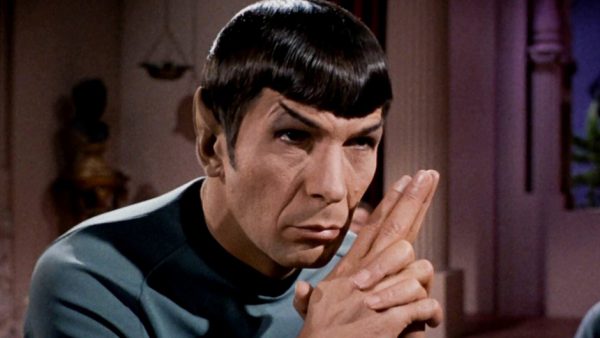

As Spock says: it's 2am, but if it was an hour earlier I'd have done another whole sketch before rendering. The side to side tilt is right, but I've leaned his head way down from what it is, making his face look bashed in. This is sort of the opposite problem from what I was having earlier, so ... yay?

As Spock says: it's 2am, but if it was an hour earlier I'd have done another whole sketch before rendering. The side to side tilt is right, but I've leaned his head way down from what it is, making his face look bashed in. This is sort of the opposite problem from what I was having earlier, so ... yay?

One of the things about learning is that regular, immediate feedback is important for progress. That's why, when I have reference material for what I'm drawing, that I post both of those here so I can compare and judge what I've done, looking for things to improve.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

One of the things about learning is that regular, immediate feedback is important for progress. That's why, when I have reference material for what I'm drawing, that I post both of those here so I can compare and judge what I've done, looking for things to improve.

Drawing every day.

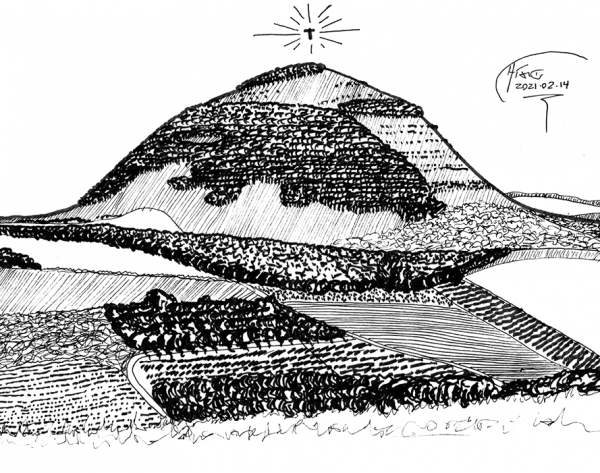

-the Centaur  Mount Tabor, sketched to commemorate the transfiguration of Jesus, that moment when Jesus is transformed on a mountaintop as he communes with Moses and Elijah, and Peter somehow loses a screw and decides it's a great time to start building houses. As Reverend Karen of St. Stephens in-the-Field and St. John the Divine memorably said in today's sermon, this was the moment that the disciples went from knowing Jesus only as a human teacher they admired to seeing him as touched with divinity. (And speaking as a religious person from a scientific perspective, this is a great example of why there always will be a gap between science and religion: even if the event actually happened exactly as described, we're unlikely to ever prove so scientifically, since it is a one-time event that cannot be probed with replicable experiments; the events of the day, even if true, really do have to be taken purely on faith. This is, of course, assuming that tomorrow someone doesn't invent a device for reviewing remote time).

Roughed on Strathmore, then rendered on tracing paper, based on the following shot taken in 2011:

Mount Tabor, sketched to commemorate the transfiguration of Jesus, that moment when Jesus is transformed on a mountaintop as he communes with Moses and Elijah, and Peter somehow loses a screw and decides it's a great time to start building houses. As Reverend Karen of St. Stephens in-the-Field and St. John the Divine memorably said in today's sermon, this was the moment that the disciples went from knowing Jesus only as a human teacher they admired to seeing him as touched with divinity. (And speaking as a religious person from a scientific perspective, this is a great example of why there always will be a gap between science and religion: even if the event actually happened exactly as described, we're unlikely to ever prove so scientifically, since it is a one-time event that cannot be probed with replicable experiments; the events of the day, even if true, really do have to be taken purely on faith. This is, of course, assuming that tomorrow someone doesn't invent a device for reviewing remote time).

Roughed on Strathmore, then rendered on tracing paper, based on the following shot taken in 2011:

צילם: אלי זהבי, כפר תבור, CC BY 2.5 , via Wikimedia Commons (Author: Eli Zehavi, Kfar Thabor)

I mean, look at that. That mountain is just begging for God do something amazing there. And if God doesn't want it, the Close Encounters mothership and H.P. Lovecraft are top of the waitlist.

It really is proving useful to ink my own rough sketches by hand, then to trace my own art. It is interesting to me though how I vertically exaggerated the mountain when I drew it, which probably explains why a few things kept not lining up the way that I wanted them to. Still ...

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

P.S. And yes, I accidentally drew the Ascension rather than the Transfiguration, which I guess is fine, because the Mount of Olives looks harder to draw. Check out that 2,000 year old tree though.

צילם: אלי זהבי, כפר תבור, CC BY 2.5 , via Wikimedia Commons (Author: Eli Zehavi, Kfar Thabor)

I mean, look at that. That mountain is just begging for God do something amazing there. And if God doesn't want it, the Close Encounters mothership and H.P. Lovecraft are top of the waitlist.

It really is proving useful to ink my own rough sketches by hand, then to trace my own art. It is interesting to me though how I vertically exaggerated the mountain when I drew it, which probably explains why a few things kept not lining up the way that I wanted them to. Still ...

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

P.S. And yes, I accidentally drew the Ascension rather than the Transfiguration, which I guess is fine, because the Mount of Olives looks harder to draw. Check out that 2,000 year old tree though.  As it says on the tin: a quick sketch of Xiao from f@nu fiku, my quasi-defunct webcomic. I forgot how complicated her character design is, and I left out a lot of it. I mean, I had forgotten that she carries a damn water bottle with her. Knowing the comic, that was probably meant to be plot significant:

As it says on the tin: a quick sketch of Xiao from f@nu fiku, my quasi-defunct webcomic. I forgot how complicated her character design is, and I left out a lot of it. I mean, I had forgotten that she carries a damn water bottle with her. Knowing the comic, that was probably meant to be plot significant:

I didn't make her easy to draw, and her outfits only get more complex as the series progresses.

Ah well. Here's hoping those sketches and thumbnails once again turn to webcomic pages.

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

I didn't make her easy to draw, and her outfits only get more complex as the series progresses.

Ah well. Here's hoping those sketches and thumbnails once again turn to webcomic pages.

Drawing every day.

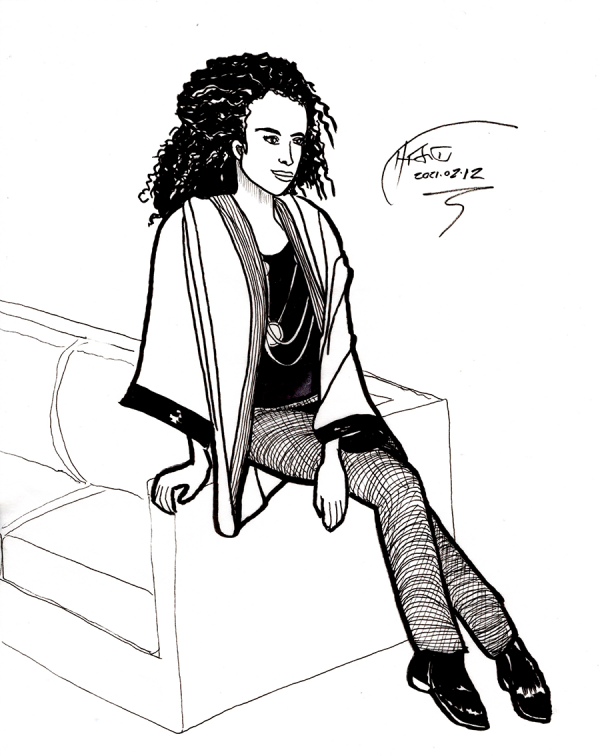

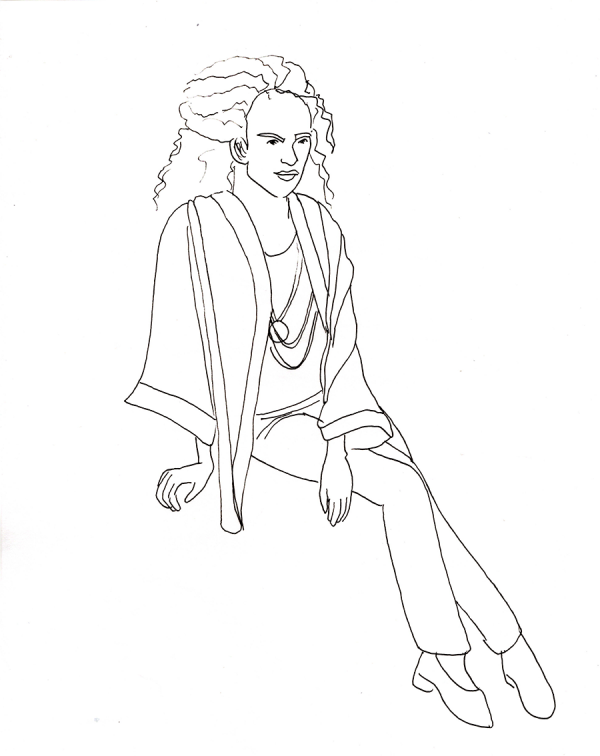

-the Centaur  Today's exercise: since I am more comfortable inking, what if I did my pencils IN ink, using tracing paper rather than the tedious erasing of pencils? I think it turned out rather well, though there's an error in the face shape I caught a bit too late and could not fully correct without starting over. Nevertheless, it's not bad. What I started with was this picture, from a local fashion catalog which came to our house:

Today's exercise: since I am more comfortable inking, what if I did my pencils IN ink, using tracing paper rather than the tedious erasing of pencils? I think it turned out rather well, though there's an error in the face shape I caught a bit too late and could not fully correct without starting over. Nevertheless, it's not bad. What I started with was this picture, from a local fashion catalog which came to our house:

This I roughed - not traced, roughed by hand - on one sheet of tracing paper:

This I roughed - not traced, roughed by hand - on one sheet of tracing paper:

Then, I corrected and tightened this drawing on a second sheet of tracing paper:

Then, I corrected and tightened this drawing on a second sheet of tracing paper:

Finally, I corrected and rendered this drawing on the third sheet of tracing paper that started the blog. If this wasn't a drawing every day exercise, I'd have started over on the face, as it was out of proportion and angle to the original reference. I think I have a tendency to straighten up heads, which makes faces that are at an angle look very weird unless I work hard to correct it.

Still ... drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Finally, I corrected and rendered this drawing on the third sheet of tracing paper that started the blog. If this wasn't a drawing every day exercise, I'd have started over on the face, as it was out of proportion and angle to the original reference. I think I have a tendency to straighten up heads, which makes faces that are at an angle look very weird unless I work hard to correct it.

Still ... drawing every day.

-the Centaur  As it says on the tin: I've been trying to improve my artwork by studying how other artists plan for success with technique and thumbnails. The author of Tigress Queen (it's great, it's my latest fave after Kill Six Billion Demons, you should go read it, heck, go read KSBD too) has a Patreon where she posts thumbnails of upcoming pages. What I love about seeing these is that she explicitly draws not just the panels and characters, but parts of the shading and spaces for the word balloons.

I think part of my artistic problem is that I rush and skip steps. Outlining is difficult since I typically do narrative outlines in my novels, so I skip to thumbnails; but pencil sketches don't look right to me, so I move too quickly to drawing inks, and thus my thumbnails aren't at a high enough level themselves to serve as useful thumbnails. Combine that with not enough practice with faces, figures, hands, and feet, and it's hard to get the needed structure in place to make the art come out as success.

Again, I keep coming back to, the solution is ...

... drawing every day.

-the Centaur

As it says on the tin: I've been trying to improve my artwork by studying how other artists plan for success with technique and thumbnails. The author of Tigress Queen (it's great, it's my latest fave after Kill Six Billion Demons, you should go read it, heck, go read KSBD too) has a Patreon where she posts thumbnails of upcoming pages. What I love about seeing these is that she explicitly draws not just the panels and characters, but parts of the shading and spaces for the word balloons.

I think part of my artistic problem is that I rush and skip steps. Outlining is difficult since I typically do narrative outlines in my novels, so I skip to thumbnails; but pencil sketches don't look right to me, so I move too quickly to drawing inks, and thus my thumbnails aren't at a high enough level themselves to serve as useful thumbnails. Combine that with not enough practice with faces, figures, hands, and feet, and it's hard to get the needed structure in place to make the art come out as success.

Again, I keep coming back to, the solution is ...

... drawing every day.

-the Centaur